In L’Italianistica oggi: ricerca e didattica, Atti del XIX Congressodell’ADI – Associazione degli Italianisti (Roma, 9-12 settembre 2015), a cura di B. Alfonzetti, T. Cancro, V. Di Iasio, E. Pietrobon, Roma, Adi editore, 2017

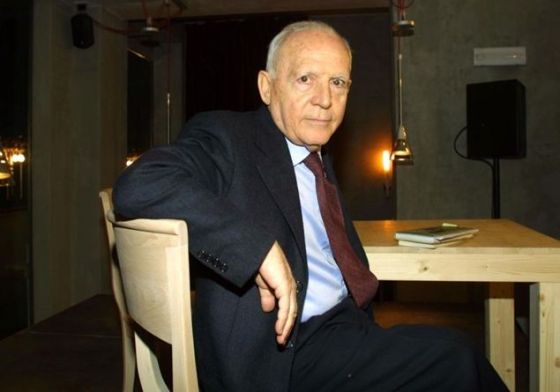

CINZIA GALLO

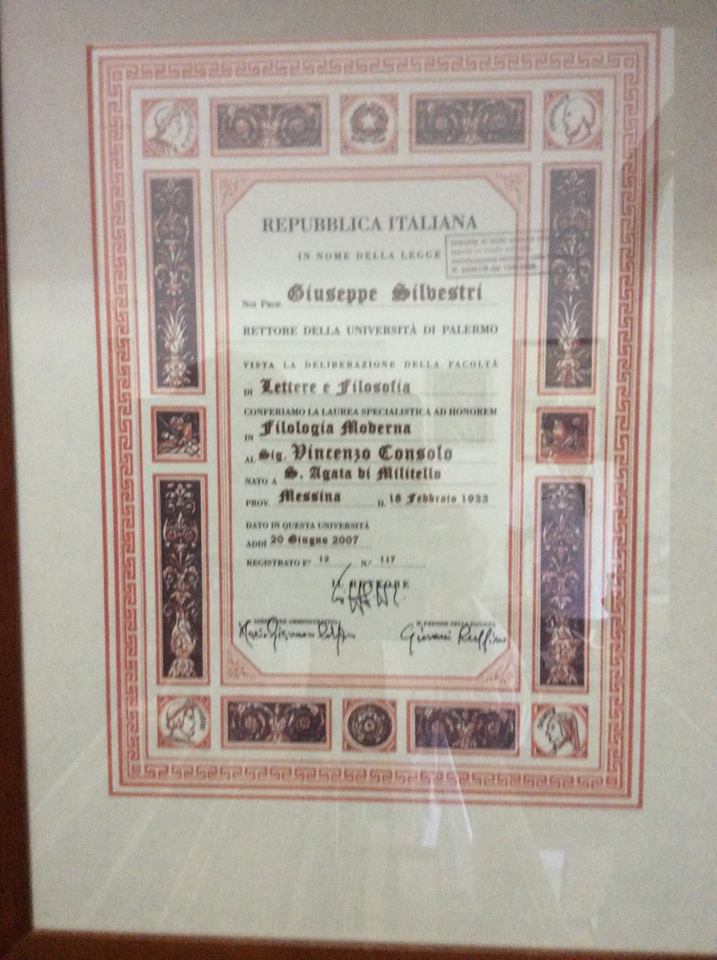

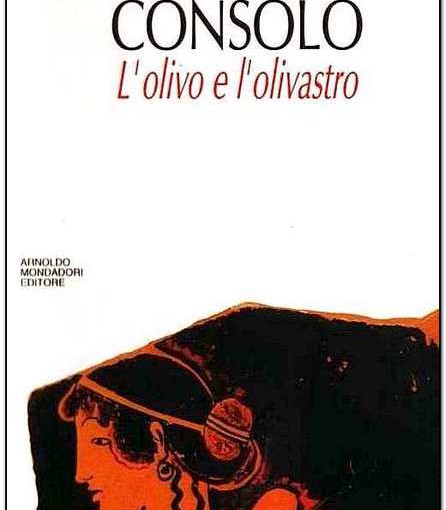

L’olivo e l’olivastro di Vincenzo

Consolo tra finzioni e funzioni della letteratura

L’olivo e l’olivastro (1994) costituisce una

tappa importante nella ricerca espressiva di Consolo, che asserendo, in

apertura, «Ora non può narrare», pone subito in evidenza la distinzione fra

scrivere e narrare e il tema dell’«afasia». Come dichiara, infatti, un’

intervista, «Ci sono momenti in cui la disperazione è tale che non trovi più

interlocutori […]. Ci sono due tipi di afasia: quella del potere, che per

definizione non vuole comunicare, e quella dell’artista che si oppone a questo

potere». In primo piano è, perciò, la funzione civile dello scrittore che,

però, mette in pericolo «il corpo letterario del racconto». Da qui il carattere

ibrido del nostro testo: i diciassette capitoli si snodano, quasi indipendenti

l’uno dall’altro, in una sorta di collage, fra narrazione, diario di viaggio,

poesia, saggio, digressioni, descrizioni. Analogamente, il gioco citazionistico

– con ricorso, anche, alla memoria interna (l’allusione a Lunaria, ed altri

testi consoliani)-, la tecnica dell’accumulo, la finzione letteraria – con le

varie voci narranti -, rappresentano un’ulteriore riflessione sull’ autoreferenzialità

della letteratura. L’olivo e l’olivastro fornisce, dunque, un chiaro esempio di

metaletteratura.

L’olivo e l’olivastro (1994) rappresenta una

tappa importante nella ricerca ideologica edespressiva di Vincenzo Consolo. Già il titolo mostra l’intreccio di

finzioni e funzioni su cui si basa. Ne Lo

spazio in letteratura, del 1999, Consolo spiega, difatti:

Anche chi qui

scrive, nella sua vicenda letteraria, […] è risalito, soprattutto nei due

ultimi libri, L’olivo e l’olivastro e

Lo Spasimo di Palermo, all’archetipo

omerico, a quell’Odissea da cui siamo

partiti. Lo spazio, in questi due romanzi, si dispiega fra due poli, Milano e

la Sicilia. Ma l’Odissea , sappiamo,

è una metafora della vita, del viaggio della vita. Casualmente nasciamo in

un’Itaca dove tramiamo i nostri affetti, dove piantiamo i nostri olivi, dove

attorno all’olivo costruiamo il nostro talamo nuziale, dove generiamo i nostri

figli. Ecco, noi oggi, esuli, erranti, non aneliamo che a ritornare a Itaca, a

ritrovare l’olivo. Lo scacco consiste nel fatto che sull’olivo ha prevalso

l’olivastro, l’olivo selvatico. 1

Il testo omerico, dunque, costituisce, secondo la terminologia

genettiana, un vero e proprio ‘ipotesto’ per Consolo, che organizza, attraverso

delle particolari finzione narrative, la funzione ideologico-civile a cui ha

sempre mirato, come precisa in Memorie:

La prosa dunque della narrazione nasce per me da un contesto storico e

allo stesso contesto si rivolge. Si rivolge con quella parte logica, di

comunicazione che sempre ha in sé il racconto. Che è, per questa sua origine

per questo suo destino, un genere letterario “sociale”. Sociale voglio dire

soprattutto perché, in opposizione tematica e linguistica al potere,

responsabile del malessere sociale […] il narratore vuole rimediare almeno

l’infelicità contingente. 2

Il

secondo capitolo de L’olivo e l’olivastro

presenta perciò Ulisse che, dopo essere approdato, «Spossato, lacero, […] in

preda a smarrimento, panico […]», nella terra dei Feaci, «trova riparo in una

tana» posta «tra un olivo e un olivastro»3 (O, 17). Il carattere simbolico di queste piante

- subito chiarito da Consolo:

- spuntano da uno stesso tronco questi due simboli

del selvatico e del coltivato, del bestiale e dell’umano, spuntano come

presagio d’una biforcazione di sentiero o di destino, della perdita di sé,

dell’annientamento dentro la natura e della salvezza in seno a un consorzio

civile, una cultura (O, 17-18).

In realtà,

tutta la vicenda di Ulisse è ripercorsa in senso simbolico: non solo «diventa

metafora che consente a Consolo di ritrovare nel mito e nella letteratura un

senso drammatico e

- V.CONSOLO, Lo

spazio in letteratura, in Di qua dal

faro, Milano, Mondadori, 1999, 270.

- CONSOLO, Memorie, in La mia isola è Las Vegas, Milano, Mondadori, 2012, 136.

- Tutte le

citazioni dal nostro testo, indicato con la lettera O, sono tratte da: V. CONSOLO, L’olivo e l’olivastro, Milano, Mondadori, 1994.

complesso

dell’esistenza personale e collettiva»,4 ma costituisce un’esortazione, per tutti gli uomini, alla lucidità,

alla ragione, a non cadere in errori generati da vicende esterne o interiori.

Mentre, difatti, la terra dei Feaci, con «il rigoglioso giardino, la […]

fastosa reggia, la saggia […] regina, […] l’accogliente corte, il popolo amico;

e l’esercizio in loro della ragione, l’amore per il canto, la poesia»,

rappresenta «una città ideale, un regno d’armonia» (O, 18), il viaggio di

Ulisse in seguito alla disfatta di Troia è «il luogo dove il reale, il

concreto, si sfalda, vanifica, e insorge l’irreale, s’installa il sogno,

l’allucinazione: il genitore dei mostri, immagini delle nostre paure, dei

nostri rimorsi» (O, 19). Ulisse si è reso colpevole, difatti, di aver costruito

il cavallo con cui Troia è stata distrutta, perciò «il racconto del viaggio di

ritorno fatto da Odisseo è quello della colpa e espiazione, della catarsi

soggettiva».5 La vicenda di Odisseo,

dunque, è «Metafora di quel che riserva la vita a chi è nato per caso nell’isola dai tre angoli: epifania crudele,

periglioso sbandare nella procella del mare, nell’infernale natura; salvezza

possibile dopo tanto travaglio, approdo a un’amara saggezza, a una disillusa

intelligenza» (O, 22). Consolo esprime allora il disorientamento del siciliano,

simbolo di tutti gli uomini, attraverso varie figure retoriche (enumerazioni,

antitesi, anafore, chiasmi), ponendo termini aulici accanto ad altri più

comuni, mettendo in evidenza la sua propensione verso quella forma espressiva

che egli stesso definisce «poema narrativo» (O, 48).

Il

nostro testo, difatti, esprime all’inizio («Ora non può narrare» [O, 9])

l’impossibilità di narrare, cioè di portare avanti, di condurre una «scrittura

creativa».6 Appunto per questo non

c’è, ne L’olivo, «una chiara diegesi,

né all’interno dei singoli capitoli, né che li colleghi fra di loro: invece, la

narrazione procede seguendo una serie di immagini ‘poetiche’, largamente

connesse, del passato».7

Fra queste, solo il meccanico terremotato racconta la propria storia in prima

persona, come accadrà alla fine del quattordicesimo capitolo, quando il

viaggiatore esprimerà il proprio disorientamento; le altre figure, chiaramente

autobiografiche, di emigranti, parlano in terza persona, in quanto, «nella

modernità le colpe non sono più soggettive, sono oggettive, sono della storia»:

di conseguenza «l’introspezione non è necessaria».8 Consolo, allora, da una

parte arricchisce i suoi exempla con

citazioni autoriali (Dante, Pisacane, Ungaretti, per esempio), dall’altra dà

nuovo significato all’ antitesi classica fra città e campagna. A Messina, Roma,

Milano, tutte rappresentate negativamente, si contrappone la «Bellissima

Toscana contadina», simbolo dei valori «del lavoro, della fatica umana» e

perciò «civilissima» (O, 13). L’esplosione della raffineria di Milazzo,

ricordata nel terzo capitolo, è l’esempio, invece, di come l’intervento

dell’uomo, sull’ambiente, non sia stato sempre positivo. La raffineria è

infatti in contrasto con «il castello, le mura saracene, sveve e aragonesi, i

torrioni […] la grotta di Polifemo, […] il porto, il Borgo, le chiese, i

conventi. […] la vasta piana […] ricca di agrumi, ulivi, viti, orti. Ricca di

gelsomini» (O, 24) fra cui si aggirava il ragazzo, recatosi a visitare i

parenti nelle Eolie (altra proiezione autobiografica, in quanto Consolo ha

realmente una sorella sposata con un notaio di Lipari, come appare nel quarto

capitolo), aspettando il treno che l’avrebbe riportato a casa. Narrare allora,

con chiara allusione a Il Narratore

di Benjamin, «significa socializzare esperienze ricordate. La narrazione […]

“attinge sempre alla memoria” e la memoria […] è “madre della poesia”, che […]

è […] l’espressione di verità condivisibili riguardo la nostra umana

condizione».9 In altre parole, il

«narratore benjaminiano […] impartisce conoscenza e cerca

- M. LOLLINI, Intrecci mediterranei. La testimonianza di

Vincenzo Consolo, moderno Odisseo, in «Italica», 82, 1 (Spring 2005),

24-43: 25.

- V. CONSOLO – M. NICOLAO, Il viaggio di Odisseo, Milano, Bompiani,

1999, 21.

- J. FRANCESE, Vincenzo

Consolo, Firenze, Firenze University Press, 2015, 4.

- Ivi, 27.

- CONSOLO – NICOLAO, Il viaggio…, 22.

- FRANCESE, Vincenzo Consolo, 86. Lo stesso Consolo spiega il termine

«narrazione» richiamandosi a Benjamin: «Dico narrazione nel senso in cui l’ha

definita Walter Benjamin in Angelus Novus.

Dice in sintesi, il critico, che la narrazione è antecedente al romanzo, che

essa è affidata più all’oralità che alla scrittura, che è il resoconto di

un’esperienza, la relazione di un viaggio. “Chi viaggia, ha molto da

raccontare” dice. “E il narratore è sempre colui che viene da lontano. C’è

sempre dunque, nella narrazione, una

attivamente di

trasformare il presente raccontando un passato personale eppur condivisibile,

passato che, per analogia, può guidare il suo pubblico verso il futuro».10 L’obiettivo è raggiunto

attraverso quella che Consolo definisce «narrazione poematica», che comporta da

una parte «la frantumazione del flusso diegetico attraverso l’inserzione di

incisi, […] immagini», dall’altra l’uso di «exempla, eventi elevati a metafora».11 Ecco, allora, che Consolo, rifacendosi a quella

che Genette chiama funzione di attestazione, menziona alcuni passi dell’ Enciclopedia Italiana Treccani, della Enciclopedia sistematica del regno vegetale,

del testo Flora sicula. Dizionario

trilingue illustrato, per mettere in rilievo le origini arabe del

gelsomino, simbolo, così, del sincretismo culturale della Sicilia ma anche

della bellezza incontaminata della pianura di Milazzo. Quella che lo storico

Giuseppe Piaggia, infatti, ritiene «uno de’ più incantevoli teatri dell’intera

Sicilia», in cui cresceva il gelsomino, «pascolavano gli armenti del Sole»,

ricordati nell’Odissea, è diventata

«una vasta e fitta città di silos, di tralicci, di ciminiere che perennemente

vomitano fiamme e fumo, una metallica, infernale città di Dite che tutto ha

sconvolto e avvelenato: terra, cielo, mare, menti, cultura» (O, 28). Affiora

così in primo piano la funzione ideologica: come i compagni di Ulisse sono

puniti per aver ucciso le vacche del Sole, così i superstiti dell’esplosione

della raffineria di Milazzo si augurano che «le neri pelli dei compagni

striscino, svolazzino nelle notti di rimorsi e sudori dei petrolieri, urlino le

membra di dolore e furore nei sogni dei ministri» (O, 28). Sotto questo segno

si conclude, anche, il quarto capitolo («Altre tempeste, altre eruzioni, piogge

di ceneri e scorrere di lave, altre incursioni di corsari investirono e

distrussero le sue Eolie, le Planctai,

le isole lievi e trasparenti, sospese in cielo, ferme nel ricordo» [O, 32]),

grazie all’anafora, ai parallelismi, all’antitesi («sospese» – «ferme»).

«lievi, […] sospese in cielo» (O, 29) sono apparse le isole anche all’inizio

del capitolo, a suggerire la struttura circolare, propria di Consolo, su cui è

costruito L’olivo e l’olivastro: alla

fine, difatti, rivedremo il meccanico di Gibellina che ripeterà: «Sono nato a

Gibellina, di anni ventitrè» (O, 9, 147). Le assonanze («lievi» –

«trasparenti»; «sospese» – «ferme»), d’altra parte, sottolineano l’importanza

degli aggettivi, uniti in quelle enumerazioni che formano la «ritrazione

musicale» caratteristica del poema narrativo («un ibrido, un incontro di logico

e di magico, di razionale-comunicativo e di lirico -poetico»12). Grazie all’

enumerazione, poi, il ricordo personale si fonde con la memoria di una civiltà,

attraverso la finzione del resoconto di un viaggio, in perfetta consonanza con

il narratore descritto da Benjamin («il narratore è pre-borghese, è colui che

riferisce un’esperienza che ha vissuto, è soprattutto quello che viene da

lontano, che ha compiuto un viaggio»13). Gli esempi sono innumerevoli, in questo

senso. Osserviamo quanto accade ad Augusta:

Il vento di

Borea, sceso dalle anguste gole del Peloro, lo sospinse alla costa dei coloni

venuti da Micene, Megara Nisea, Calcide, Corinto, tra Megara Hyblea e Thapsos,

lo portò nel golfetto più in là di punta Izzo, nel témenos di smarrimento e allucinazione, d’incanto e rapimento

, dove, nella luce aurorale d’un agosto, al giovane studioso di

dialetti ionici, apparve, emergendo dal mare, la creatura sublime e brutale,

adolescente e millenaria, innocente e sapiente, la sirena silente [omoteleuto]

che invade e possiede, trascina nelle immote dimore [assonanza], negli abissi

senza tempo, senza suono (O, 33).

In altri casi

le immagini del mito, inserite in metafore, combinate con altre figure

retoriche (anafore, enumerazioni), servono a rafforzare la degenerazione del

presente:

Corre sulla strada

per Siracusa, lungo la costa bianca e porosa di calcare, ai piedi del tavolato

degli Iblei, va oltre Tauro, Brùcoli, Villasmundo, va dentro l’immenso inferno

di ferro e fiamme, vapori e fumi, dentro fabbriche di cementi e concimi, acidi

e diossine, centrali termoelettriche e raffinerie, dentro Melilli e Priolo di

cilindri e piramidi, serbatoi di

lontananza

di spazio e di tempo”. E c’è, nella narrazione, un’idea pratica di giustezza e

di giustizia, un’esigenza di moralità» (I

ritorni, in Di qua dal faro,

144).

- Ivi, 64.

- Ivi, 71.

- CONSOLO, L’invenzione della lingua, in «MicroMega», 5 (1996), 115

nafte, oli,

benzine, dentro il regno sinistro di Lestrigoni potenti, di feroci giganti che

calpestano uomini, leggi, morale, corrompono e ricattano, devìa per Agosta,

l’Austa sul chersoneso fra due porti, Xifonio e Megarese, nell’isola congiunta

alla terra da due ponti. La città dei due Augusti, il romano e lo svevo, chiusa

nel superbo castello, nei baluardi, nelle mura, circondata da scogli con forti

dai nomi sonanti, Ávalos, García, Vittoria, crollati per terremoti e guerre e

sempre ricostruiti, varcata la Porta Spagnola, gli appare nella luce cinerea,

nella tristezza di un’Ilio espugnata e distrutta, nella consunzione

dell’abbandono, nell’avvelenamento di cielo, mare, suolo (O, 34).

Attraverso

un inciso («Come sempre le guerre»), poi, il narratore dà valore generale alla

singola esperienza, che pone sullo stesso piano lo scempio causato dagli uomini

e quello determinato dalle calamità naturali:

Contro lo sfondo di caserme mimetiche e hangar vuoti e forati da

raffiche e schegge, contro lo scenario fermo di un’ultima guerra di follia e

massacro, come sempre le guerre, erano le nuove macerie del terremoto d’una

notte di dicembre che aveva aperto tetti, mura di case, chiese, inclinato

colonne, paraste, mutilato statue, distrutte e rese fantasma le case della

Borgata (O, 34).

Sono

allora le città del passato, come asserito anche in Retablo, a rappresentare gli aspetti positivi, i valori smarriti al

presente, con palese richiamo all’ «inversione storica»14 di Bachtin. Lo

sottolineano le anafore, le enumerazioni, il poliptoto, le metafore:

Ama quella sua

città, non vede quelle mura dirute, quelle chiese puntellate da travi, quelle

case deserte, quel porto, quel mare oleoso invaso da petroliere, quella

campagna intorno di ulivi e mandorli neri, quelle spiagge caliginose e

affollate di bagnanti, quell’orizzonte, quello sky-line di tralicci, di tubi,

di silos. Amano [poliptoto], lui e lo zio professore, pensionato della scuola,

la città del passato, antecedente a quella dei Romani, a quella che il gran

Federico munì di castello e privilegi, la remota città che conoscono in ogni

pietra, in ogni vicenda, su cui insieme scrivono una notizia, una guida: amano

un sogno, un mondo lontano, lontano [anadiplosi] dall’orrore presente (O, 35).

Rappresentano

dunque, questi moduli espressivi, l’unica possibilità in un periodo di crisi. I

rapporti «tra parola e realtà nella società contemporanea»15 sono del resto discussi

nel sesto capitolo, di chiaro orientamento metaletterario, che ripropone, in

apertura, la situazione già presentata in Catarsi.

Anche qui, infatti, Pausania dichiara di essere «il messaggero, l’ ánghelos», a cui «è affidato il dovere

del racconto: conosco i nessi, la sintassi, le ambiguità, le malizie della

prosa, del linguaggio..» (O, 39). Ma Empedocle, analogamente che in Catarsi, definisce «ogni parola […]

misera convenzione» (O, 41), per cui pronuncia «parole d’una lingua morta, / di

corpo incenerito, privo delle scorie / putride dello scambio, dell’utile / come

la lingua alta, irraggiungibile, / come la lingua altra, oscura, / della Pizia

o la Sibilla / che dall’antro libera al vento mugghii, foglie…» (O, 44).

Queste posizioni, d’altra parte, porteranno Consolo a dichiarare, in I ritorni:

Ma oggi, in

questa nostra civiltà di massa, in questo mondo mediatico, esiste ancora la

possibilità di scrivere il romanzo? Crediamo che oggi, per la caduta di

relazione tra la scrittura letteraria e la situazione sociale, non si possano

che adottare, per esorcizzare il silenzio, i moduli stilistici della poesia;

ridurre, per rimanere nello spazio letterario, lo spazio comunicativo, logico e

dialogico proprio del romanzo. 16

- M.BACHTIN, Estetica

e romanzo, Einaudi, Torino 1979, 294.

- M.ATTANASIO, Struttura-azione di poesia e narratività

nella scrittura di Vincenzo Consolo, in «Quaderns d’Italià», 10, 2005, 26.

- CONSOLO, I ritorni, 145.

E ne Lo

Spasimo di Palermo:

Abborriva il

romanzo, questo genere scaduto, corrotto, impraticabile. Se mai ne aveva

scritti, erano i suoi in una diversa lingua, dissonante, in una furia verbale

ch’era finita in urlo, s’era dissolta nel silenzio. Si doleva di non avere il

dono della poesia, la sua libertà, la sua purezza, la sua distanza

dall’implacabile logica del mondo. 17

Consolo concludeva, in tal modo, un discorso

iniziato precedentemente, in Fuga

dall’Etna e in

Nottetempo,

casa per casa. Nel primo,

aveva asserito:

Il romanzo […] sta degenerando […] Si stampano tanti romanzi oggi, e più

se ne stampano più il romanzo si allontana dalla letteratura. Un modo per

riportarlo dentro il campo letterario penso sia quello di verticalizzarlo,

caricarlo di segni, spostarlo verso la zona della poesia, a costo di farlo

frequentare da ‘felici pochi’. 18

- in Nottetempo,

casa per casa:

- è

possibile ancora la scansione, l’ordine, il racconto? E’ possibile dire dei

segni, dei colori, dei bui e dei lucori, de grumi e degli strati, delle

apparenze deboli, delle forme che oscillano all’ellisse, si stagliano a

distanza, palpitano, svaniscono? E tuttavia per frasi monche, parole difettive,

per accenni, allusioni, per sfasature e afonie tentiamo di riferire di questo

sogno, di questa emozione. 19

Modello,

allora, della nuova forma narrativa sono I

Malavoglia, privi di «intreccio […] di romanzesco» (O, 48). I suoi moduli

espressivi corrispondono a un dolore assoluto:

Un poema narrativo, un’epica popolana, un’odissea chiusa, circolare, che

dà il senso, nelle formule lessicali, nelle forme sintattiche, nel timbro

monocorde, nel tono salmodiante, nei proverbi gravi e immutabili come sentenze

giuridiche o versetti di sacre scritture, Bibbia, Talmud o Corano, dà il senso

della mancanza di movimento, dell’assenza di sviluppo, suggerisce l’immagine

della fissità: della predestinazione, della condanna, della pena senza rimedio

(O, 48).

Ma,

secondo Consolo, al presente la situazione è degenerata: la speculazione

edilizia ha fatto sparire «le casipole, le barche, i fariglioni. […] gli

scogli, la rupe del castello di Aci, il Capo Mulini, l’intero orizzonte» (O,

49), in contrapposizione a Vizzini, luogo carico di memorie verghiane. Si

verifica, di conseguenza, la «fine del poema», con un «turbinìo di parole,

suoni privi di senso, di memoria» (O, 49). Un esempio è l’accumulo di termini

che descrivono il procedere del viaggiatore lungo la costa catanese:

Va dentro il

frastuono, la ressa, l’anidride, il piombo, lo stridore, le trombe, gli

insulti, la teppaglia che caracolla, s’accosta, frantuma il vetro, preme alla

tempia la canna agghiacciante, scippa, strappa anelli collane bracciali, scappa

ridendo nella faccia di ceffo fanciullo, scavalca, s’impenna, zigzaga fra spazi

invisibili, vola rombando, dispare. Va lungo la nera scogliera, il cobalto del

mare, la palma che s’alza dai muri, la buganvillea, l’agave che sboccia tra i

massi, va sopra l’asfalto in cui sfociano tutti gli asfalti che ripidi scendono

dalle falde in cemento del monte, da Cibali Barriera Canalicchio Novalucello,

oltrepassa Ognina, la chiesa, il porto d’Ulisse, coperti da cavalcavie rondò

svincoli raccordi motel palazzi – urlano ai margini venditori di pesci, di

molluschi di nafta -, oltrepassa la rupe e il castello di lava a picco sul

mare, giunge al luogo dello stupro, dell’oltraggio (O, 46-47).

- V. CONSOLO, Lo

Spasimo di Palermo, Milano, Mondadori, 1998, 105.

- V. CONSOLO, Fuga dall’Etna. La Sicilia e Milano, la

memoria e la storia, Roma, Donzelli, 1993, 60-61.

- V. CONSOLO, Nottetempo,

casa per casa, Milano, Mondadori, 1992, 68-69.

Che Catania sia «pietrosa e inospitale, emblema

d’ogni luogo fermo o imbarbarito» (O, 58),

- dimostrato dalla scarsa

attenzione riservata, già dai suoi stessi contemporanei, a Verga, che viene

così a rappresentare l’intellettuale esule nella sua stessa città, un «inferno

[….] che sempre e in continuo fu coperta dalle lave, squassata e rovinata dai

tremuoti» (O, 57). Da qui la «sfida spavalda e irridente» (O, 57) degli

abitanti, che rivolgono, invece, la loro attenzione a Rapisardi, «il

versificatore vuoto e roboante» (O, 58). Quando, perciò, Catania organizza una

cerimonia per festeggiare gli ottant’anni di Verga, costui vede ben chiare «le

due facce […] di quella odiosamata sua città, di quel paese: la maschera

ottusa, buffona e ruffiana della farsa e quella furba e falsa della retorica,

dell’eroismo teatrale e decadente» (O, 62). E non è certamente un caso che sia

Pirandello a rendersi conto dell’estraneità di Verga, che un sapiente uso

dell’aggettivazione, delle figure retoriche (anafore, metafore, enumerazioni)

sottolineano, costituendo un ulteriore esempio di scrittura poematica:

Pirandello lo

osservò ancora e gli sembrò lontano, irraggiungibile, chiuso in un’epoca

remota, irrimediabilmente tramontata. Temette che né il suo, né il saggio di

Croce, né il vasto studio del giovane Russo avrebbero mai potuto cancellare

l’offesa dell’insulsa critica, del mondo stupido e perduto, a quello scrittore

grande, a quell’Eschilo e Leopardi della tragedia antica, del dolore, della

condanna umana. Pensò che, al di là dell’esterna ricorrenza, delle formali

onoranze, in quel tempo di lacerazioni, di violenza, di menzogna, in quel

tramonto, in quella notte della pietà e dell’intelligenza, il paese, il mondo,

avrebbe ancora e più ignorato, offeso la verità, la poesia dello scrittore.

Pensò che quel presente burrascoso e incerto, sordo alla ritrazione, alla

castità della parola, ebbro d’eloquio osceno, poteva essere rappresentato solo

col sorriso desolato, con l’umorismo straziante, con la parola che incalza e

che tortura, la rottura delle forme, delle strutture, la frantumazione delle

coscienze, con l’angoscioso smarrimento, il naufragio, la perdita dell’io.

Pensò che la Demente, la sua Antonietta, la suor Agata della Capinera, la povera madre, il fratello

suicida di San Secondo, ogni pura fragile creatura che s’allontana, che

sparisce, non è che un barlume persistente, segno di un’estrema sanità nella

malattia generale, nella follia del presente (O, 67).

.

Difatti,

se, come è noto, Consolo individua una differenza fra la cultura della parte

orientale dell’isola, in cui collochiamo Verga, interessata ai temi

dell’esistenza, della natura, e quella della parte occidentale, di cui è

rappresentante Pirandello, orientata ai problemi della storia, sono questi,

adesso, ad essere considerati più urgenti. Nel decimo capitolo, perciò, il

viaggiatore, giunto a Caltagirone, incontra la sua amica Maria Attanasio, un

vero e proprio modello di intellettuale e scrittrice. Vive in disparte «dal

mondo», in quanto, consapevole degli aspetti negativi della sua terra, «come tutti

i poeti ama un altro mondo, un altro paese» (O, 71). Analogamente alla

protagonista del suo romanzo Correva

l’anno 1698 e in città avvenne il fatto memoriabile,

Maria, allora, «s’era mascherata da uomo, da poliziotto, per combattere

l‘incuria, ildisordine

amministrativo, il sopruso mafioso» (O, 75), che si riflettono nella

conformazione della città, in linea con la grande importanza che Consolo

attribuisce, sempre, alla geografia, agli spazi. «Al di qua del paese saraceno,

giudeo, genovese e spagnolo, […] è sulla piana un altro paese speculare di

cemento: quartieri e quartieri uniformi di case nuove e vuote, deserte. […]

mostruosità nate dalla cultura di massa, […]» (O, 70). La condanna di questa,

che ha provocato la perdita della memoria, della storia, testimoniate dalle

ceramiche delle facciate di edifici pubblici e privati – a rivelare il

carattere visivo-figurativo20

della scrittura consoliana, è senz’appello, grazie, sempre, alle figure

retoriche utilizzate:

- Infatti, «[…] la historia

de la escritura de Vincenzo Consolo puede reconstruire idealmente a partir de

una percepción cromática desarrollada en una página inédita, […] El narrador

incipiente […] estaría ofreciendo ya una de las claves de construcción – y de

lectura – de su obra futura: “Pensate a un quadro”» (M.Á. CUEVAS, Ut Pictura: El imaginario iconográfico en la obra de Vincenzo Consolo,

in «Quaderns d’Italià», 10 (2005), 63-77: 64). Lo stesso Consolo, del resto,

dichiara in un’intervista: «Sempre ho avvertito l’esigenza di equilibrare la

seduzione […] della parola con la visualità, con la visione di una

concretezza visiva» (D. O’CONNELL,

Il dovere del racconto: Interview with

Vincenzo Consolo, in «The Italianist», 24: II, 2004, 251)-

Sembra così,

questo piccolo paese nel cuore della Sicilia, il plastico, l’emblema del più

grande paese, della vecchia Italia che ha generato dopo i disastri del

fascismo, nei cinqant’anni di potere, il regime democristiano, la trista,

alienata, feroce nuova Italia del massacro della memoria, dell’identità, della

decenza e della civiltà, l‘Italia corrotta, imbarbarita, del saccheggio, delle

speculazioni, della mafia, delle stragi, della droga, delle macchine, del

calcio, della televisione e delle lotterie, del chiasso e dei veleni. Il

plastico dell’Italia che creerà altri orrori, altre mostruosità, altre

ciclopiche demenze (O, 71).

I

danni della cultura di massa, verso cui Consolo è sempre molto critico,21 sono chiari a Gela, dove

un ragazzo, «nutrito» di una «demente cultura», di «libri di vuote

chiacchiere», «della furbastra e volgare letteratura sulla degradazione e la

marginalità sociale», come appare nei «serials televisivi, […] Piovra 1, Piovra 2, Piovra 3…»,

dimenticando «ogni cognizione del giusto e dell’ingiusto, della pietà e della

ferocia, ogni fraterno affetto» (O, 80-81), ha ucciso il fratello per futili

motivi. Il verbo ‘nutrire’, ripetuto in anafora, è ovviamente usato in funzione

antifrastica, in quanto è evidente che la cultura ha perso ogni aspetto

formativo e solo la scrittura poematica può alludere a tale degenerazione

(«Dire di Gela nel modo più vero e forte, dire di questo estremo disumano,

quest’olivastro, questo frutto amaro, questo feto osceno del potere e del

progresso, dire del suo male infinite volte detto, dirlo fuor di racconto, di

metafora, è impresa ardua o vana» [O, 77]). Riprendendo infatti quanto asserito

in Memorie («in questo ibrido

letterario che è il racconto», la «parte logica [ …] può invadere per

altissima febbre civile tutta la colonnina, […] con […] rischi mortali per

il corpo letterario del racconto»,22 Consolo adesso dichiara: «Ma oltre Gela o

Milazzo, Augusta o Catania, è in questo tempo per chi scrive un mortale rischio

tradire il campo, uscire dal racconto, negare la finzione e il miele

letterario, riferire d’una realtà vera, d’un ritorno amaro, d’un viaggio nel

disastro [O, 77]). L’intellettuale, difatti, al presente non è ascoltato.

Consolo, di conseguenza, svela le cause del malessere di Gela attraverso una

prosa che adotta, ancora una volta, l’andamento ritmico della poesia (grazie

all’anafora, all’enumerazione, alla metafora, all’allitterazione) e in cui

convivono termini aulici («obliato»), anche di memoria montaliana («cocci»,

«muraglia»), con altri più comuni:

Da quei pozzi,

da quelle ciminiere sopra templi e necropoli, da quei sottosuoli d’ammassi di

madrepore e di ossa, di tufi scanalati, cocci dipinti, dall’acropoli sul colle

difesa da muraglie, dalla spiaggia aperta a ogni sbarco, dal secco paese povero

e obliato partì il terremoto, lo sconvolgimento, partì l’inferno d’oggi. Nacque

la Gela repentina e nuova della separazione tra i tecnici, i geologi e i

contabili giunti da Metanopoli, chiusi nei lindi recinti coloniali, palme

pitosfori e buganvillee dietro le reti, guardie armate ai cancelli, e gli

indigeni dell’edilizia selvaggia e abusiva, delle case di mattoni e tondini

lebbrosi in mezzo al fango e all’immondizia di quartieri incatastati, di strade

innominate, la Gela dal mare grasso d’oli, dai frangiflutti di cemento, dal

porto di navi incagliate nei fondali, inclinate sopra un fianco, isole di

ruggini, di plastiche e di ratti; nacque la Gela della perdita d’ogni memoria e

senso, del gelo della mente e dell’afasìa, del linguaggio turpe della siringa e

del coltello, della marmitta fragorosa e del tritolo (O, 78-79).

- In un’intervista del 2007,

Consolo osserva che con la mutazione antropologica «teorizzata da Pasolini. Il

nostro Paese si modernizzava velocemente, subendo però i modelli importati

dall’esterno. Da qui un asservimento culturale, linguistico negli usi, nei

costumi e nei consumi. […] Da qui la perdita di ogni forza espressiva e di

ogni verità storica» («Consolo ‘Le ombre della nostra cultura’». Intervista.

laRepubblica.it,

- novembre 2007, 1). Tre anni

prima, del resto, ha ricordato con piacere come «il poeta ed etnologo Antonino

Uccello, […] nel momento della grande mutazione antropologica, vale a dire

della fine della civiltà contadina», sia riuscito a raccogliere «antichi canti

popolari» (Consolo, Pino Veneziano e la canzone popolare, Milano 19 luglio

2004, pinoveneziano.altervista.org/consolo_e_fo.html). Critiche alla

televisione sono anche contenute in La

pallottola in testa (La mia isola è

Las Vegas, 157-162).

Ed

è proprio l’importanza attribuita alla storia e alla memoria a tenere lontano

Consolo dal postmodernismo, come ha puntualizzato Norma Bouchard.23 Consolo immagina allora

che dalle rovine del tempio di Atena, che quindi si pongono come depositarie e

custodi di autentici valori, si elevino alcuni versi dell’Agamennone di Eschilo («Quale

erba cresciuta / nel veleno, quale

acqua

- sgorgata dal fondo del mare / hai

ingoiato...» [O, 81]). Analogamente, le citazioni che,nell’undicesimo capitolo, descrivono Siracusa24 non possono essere

ricondotte al gioco citazionistico del postmodernismo, ma mettono in evidenza

come questa città, «d’antica gloria», rappresenti «la storia dell’umana civiltà

e del suo tramonto» (O, 84). Siracusa, descritta con la consueta tecnica

dell’accumulo («Molteplice città, di cinque nomi, d’antico fasto, di potenza,

d’ineguagliabile bellezza, di re sapienti e di tiranni ciechi, di lunghe paci e

rovinose guerre [chiasmo], di barbarici assalti e di saccheggi» [O, 83]),

oppone, alla decadenza del presente, i valori della storia e della poesia, in

quanto costituisce la «patria d’ognuno […] che conserva cognizione

dell’umano, della civiltà più vera, della cultura» (O, 84). Appunto per questo

Consolo ricorda il soggiorno a Siracusa di importanti personaggi (Maupassant,

Von Platen), i quali, spinti «a viaggiare per quel Sud mediterraneo che,

nell’abbaglio, nella mitologia poetica, aveva ereditato dalla Grecia la

Bellezza», vi trovano una città «dell’infinito tramonto e dell’abbandono» (O,

102). È proprio il verbo ‘trovare’, ripetuto in anafora, ad attestare lo scarto

tra le aspettative di Von Platen, che cerca «come consolazione al suo male,

rimedio al suo scontento, solo bellezza ed armonia greca» (O, 103), e la

realtà:

Trova vento e

tempesta quell’inizio d’inverno a Siracusa, la tramontana che sferza il mare

del porto Grande, piega i ficus della passeggiata Adorno, i papiri del Ciane,

illividisce la facciata barocca del Duomo d’Atena e di Santa Lucia, le colonne

dei templi, le pareti delle latomie. Trova solitudine e disperazione, consunto

dalla febbre, dal vomito, dalla dissenteria, trova la morte nella povera

locanda Aretusa di via Amalfitania (O, 103).

Due

secoli prima, del resto, pure Caravaggio ha giudicato Siracusa un «ammasso di

macerie», un «fosso di miseria e d’abbandono» (O, 90). La pochezza

intellettuale della città è dimostrata dal discorso del vescovo di fronte al

quadro di Santa Lucia commissionato a Caravaggio, discorso perfettamente in

linea con l’idea consoliana del racconto come genere «ibrido»,25 in cui le enumerazioni si

combinano con le anafore («non possiamo», «nostro-nostra»), con l’anadiplosi

(«perdoni, perdoni»):

- La Santa

nostra Lucia ci perdoni, perdoni la nostra stoltezza e il nostro inganno. Noi

non possiamo ora celebrare, avanti a questo scempio, a quei brutali ignudi

incombenti sull’altare, al cadavere reale della donna, a una santa priva di

nimbo, a quello squarcio sanguinoso sul suo collo, ai fedeli impiccioliti, al

vescovo nascosto…, non possiamo celebrare il santo sacrificio della Messa,

non possiamo benedire questo quadro. L’artista capisca e si studi

d’aggiustare… (O, 94-95).

La reazione di

Caravaggio, che sembra ricordare Fabrizio Clerici di Retablo per il suo legame con il paggio Martino e per aver visto

una «turba d’infelici, accattoni e infermi»26 (O, 91) nelle strade della città, è di uscire

«nella piazza vasta, nella luce del mattino» (O, 95): vastità di spazi e

- «It is

important to point out that even though Consolo’s novels exhibit many of the

rhetorical devices that we have come to associate with postmodern writing

practices, they also remain fundamentally distinct from dominant, majoritarian

forms of postmodernism» (N. BOUCHARD, Consolo and the Postmodern

Writing of Melancholy, «Italica»,

82, 1 [Spring 2005, 5-23: 10-11]).

- «’I’ son

Lucia; / lasciatemi pigliar costui che dorme; / sì l’agevolerò per la sua via’»

(Purgatorio, XI, 55-57), (O,

83); «Calava a Siracusa senza luna / La notte e

l’acqua plumbea / E ferma nel suo fosso riappariva, / Soli andavamo dentro la rovina, / Un cordaro si mosse dal

remoto (G. UNGARETTI, Ultimi cori per la terra promessa, in Vita d’un uomo. Tutte le poesie, a cura di L. PICCIONI, Milano, Mondadori, 1982,

281), (O, 84).

- CONSOLO, Memorie…, 136.

- Clerici

incontra, per le strade di Palermo, «una folla d’accattoni, finti storpi o

affetti da morbi repugnanti» (CONSOLO, Retablo, Milano, Mondadori,

2000, 11).

luce, in

sostanza, in contrapposizione alle tenebre dell’ignoranza.27 Ma, al presente, la

degenerazione è tale che gli spazi, i luoghi non riescono più ad influire sul

modo di pensare. Se, perciò, ad Avola, «La vasta piazza quadrata, il centro del

quadrato inscritto nell’esagono, lo spazio in cui sfociano le strade del mare,

dei monti, di Siracusa, di Pachino, fu sempre il teatro d’ogni incontro,

convegno, assemblea, dibattito civile, la scena dove si proclamò il progetto,

si liberò il lamento, l’invettiva» (O, 110), adesso essa è «vuota, deserta,

sfollata come per epidemia o guerra» (O, 112). Responsabile è l’omologazione,

l’avvento della cultura di massa: tanti giovani, «con l’orecchino al lobo, i

lunghi capelli legati sulla nuca, che fumano, muti e vacui fissano la vacuità

della piazza come in attesa di qualcuno, di qualcosa che li scuota, che li

salvi. O li uccida» (O, 112). Tutte le costruzioni umane, dunque, anche quelle

che insistono nello spazio, testimoniano la crisi: il viaggiatore che giunge a

Siracusa, di conseguenza, ritiene giusto che le lacrime della Vergine, «nel

presente oscuro e allarmante, si siano unite, solidificate nel cemento di una

immensa lacrima» [il santuario della Medonna delle Lacrime] (O, 100).

L’impressione negativa causata dal degrado, dall’incuria in cui versano gli

edifici di Noto è rafforzata, ancora una volta, dalle enumerazioni,

dall’accurata scelta di aggettivi, sostantivi, verbi:

Il suo tufo

dorato si è corroso, sfaldato, le sue architetture di stupore si sono

incrinate, i fregi son crollati per vecchiezza, inquinamento, incuria, per le

infinite, ricorrenti scosse del suolo. […] chiese e palazzi e conventi

pericolanti, imbracati, puntellati da fitti tubi di ferro, da tavole e travi,

invasi nelle fenditure, nelle crepe, nei làstrici, nelle logge evacuate, da

cespugli di rovi, da edere, fichi selvatici. […] un liceo, un vasto edificio

sulla via principale puntellato da travi. Dentro era tutto disfatto, corroso,

divorato dal cancro, invaso dalle erbe, sepolto dalla polvere del tufo (O,

116-117).

I luoghi, però,

mettendo in modo il meccanismo della memoria, consentono di tramandare dei

principi che dovrebbero far riflettere. Il viaggiatore, infatti, ricordando,

davanti al mare, un viaggio compiuto in Africa, fino ad Utica, dove il ricordo

dei versi di Dante fa sentire ancora vivo l’esempio di Catone, come altri

«luoghi antichi e obliati, bagnati da quel Mediterraneo, […] Tindari,

Solunto, Camarina, Eraclea, Mozia, Nora, e Argo, Thuburbo Majus, Cirene, Leptis

Magna, Tipaza… […] Algeri, dove don Miguel scriveva l’ottava […] per il

poeta Antonio Veneziano», sente di odiare «la sua isola terribile, barbarica,

la sua terra di massacro, d’assassinio, odia il suo paese piombato nella notte,

l’Europa deserta di ragione» (O, 105). Quest’immagine è amplificata dapprima

attraverso l’anafora, l’enumerazione, il richiamo al sacrificio di Ifigenia,

poi con la citazione di un passo del Lamento

della città caduta di Ducas, presente pure, come epigrafe,28 in Retablo. Questo esempio di memoria interna, insieme ai riferimenti

a Lunaria,29 a Lo Spasimo di Palermo, a Il

sorriso dell’ignoto marinaio, a Le

pietre di Pantalica attesta i profondi legami esistenti fra le varie opere

di Consolo, la loro sostanziale unitarietà oltre che una riflessione sull’

autoreferenzialità della letteratura. A questa, in sostanza, spetta mantenere

in vita un patrimonio di idee destinato, altrimenti, a tramontare. Il

viaggiatore nota, difatti, non solo che la vecchia madre ha dimenticato tutto

il «carico di pene, di ricordi» (O,

- della sua esistenza, ma

pure che la casa dove era cresciuto con la sua famiglia è stata abbattuta per

far posto a un nuovo quartiere. Nato in un paese «ai piedi dei Nèbrodi» (O,

122), egli, dietro cui è ormai facile scorgere lo stesso Consolo, decide di

viaggiare, di andare «verso occidente, verso i luoghi della storia» (O, 123),

che attestano il sincretismo culturale sempre

- Cfr., sul motivo della luce

nei testi di Consolo, P. CAPPONI,

Della luce e della visibilità.

Considerazioni in margine all’opera

di Vincenzo Consolo, in «Quaderns d’Italià», 10, 2005, 49-61.

- L’importanza, la funzione delle epigrafi sono

chiarite da Consolo in Le epigrafi, (Di qua dal faro,198-202).

- A Noto,

il viaggiatore ricorda di avere assistito, «anni prima alla rappresentazione di

un’operetta barocca, una favola in cui si narrava d’un viceré malinconico e

d’una luna che si sfalda e che cade. / Ma

la Luna, la Luna la Luna / la maculata

Luna è dissonanza, / è creatura atonica, scorata, / caduta dalla traccia del

suo cerchio, / vagante negli spazi desolanti» (O, 117). Questi versi sono,

appunto, in Lunaria (Torino, Einaudi,

1985,52).

molto caro al

nostro autore. Egli si innamora, infatti, di Cefalù, in cui le radici arabe e

normanne sono perfettamente fuse, «siccome accanto e in armonia stavano il gran

Duomo o fortezza o castello di Ruggiero e le casipole con archi, altane e

finestrelle del porto saraceno, del Vascio o la Giudecca»30 (O, 124). A Cefalù trova

il ritratto dell’Ignoto, «che un barone, un erudito, amante d’arte, aveva

trovato nelle Eolie e insieme poi ad una sua raccolta aveva lasciato in dono al

suo paese» (O, 124). Il percorso compiuto dal quadro, «dal mare verso la

terra», descritto in apertura de Il sorriso

dell’Ignoto marinaio, sembra perciò coincidere con quello del viaggiatore,

cioè «dall’esistenza alla storia, dalla natura alla cultura» (O, 124), alla

grande storia di Palermo. Ma la crisi, il decadimento è tale che il quadro di

Antonello non può più costituire un punto di riferimento: esso è diventato,

semmai, “Le pitture nere” di Goya. Arrivato a Palermo, allora, il viaggiatore

decide di non fermarsi. Se, al solito, le enumerazioni marcano questa

raffigurazione negativa, riprendendo quanto affermato ne Le pietre di Pantalica31 («Non volle fermarsi in quel luogo

dell’agguato, del crepitio dei kalashnikov e del fragore del tritolo, delle

membra proiettate contro alberi e facciate, delle strade di crateri e di

sangue, dell’intrigo e del ricatto, delle massonerie e delle cosche, in quel

luogo dell’Opus Dei, degli eterni Gesuiti del potere e dei politici di retorica

e spettacolo, della plebe più cieca e feroce, della borghesia più avida e

ipocrita, della nobiltà più decaduta e dissennnata»), un’interrogativa rileva

come, ormai, il disfacimento sia generale («Ma è Palermo o è Milano, Bologna,

Brescia, Roma, Napoli, Firenze?» [O, 125]). Nemmeno i luoghi delle antiche

civiltà, allora, possono dirsi custodi di antichi, autentici valori: Segesta è

«dissacrata» dagli incendi dolosi, dalle «comitive chiassose» (O, 126), così

come lo è il teatro greco di Siracusa, ne Le

pietre di Pantalica. Analogamente, Trapani, «città d’un tempo degli scambi,

del porto affollato di velieri, della rotta per Tunisi e Algeri, della civiltà

dei commerci, di banchi, di mercati, di ràbati e giudecche, di botteghe», è

adesso «caduta nel dominio delle logge, delle cosche mafiose più segrete e più

feroci» (O, 129). Dimostra questi concetti, sottolineati da assonanze

(banchi-mercati- ràbati; giudecche -botteghe) ed allitterazioni, l’omicidio del

giudice Ciaccio Montalto, tanto più grave in quanto il giudice «crea una verità, quella giuridica,

definitiva e incontrovertibile, di fronte alla quale la verità storica non ha

più valore» (O, 132). E a testimoniare lo stravolgimento di valori e principi,

il viaggiatore vede, in una stanza del museo, di un luogo, cioè, che di per sé

custodisce le memorie del passato, una ghigliottina, rimasta in funzione fino

agli anni successivi all’unificazione italiana. Gli appare quale

«rappresentazione della giustizia assurta a crudele astrazione, a geometrica

follia, a demente iterazione rituale, a terrifica recitazione» (O, 130): ciò

significa attribuire una motivazione storica alla contemporanea degenerazione

della Sicilia. Consolo, del resto, si mostra attento ai fatti di Bronte,32 alle rivolte di Cefalù, di

Alcàra Li Fusi. Solo dalla letteratura, dunque, potrebbe giungere una salvezza,

come sarà evidenziato ne Lo Spasimo di

Palermo. Perciò, se scrittori come

Hugo, Camus guardano con «raccapriccio» (O, 130) allaghigliottina, Consolo immagina che, ad Erice, mentre gli

scienziati «Parlano e parlano, enunciano teorie, scoperte, espongono programmi,

[… ] contrastano come gli antichi cerusici al capezzale del malato» (O, 134),

il suo amico Nino De Vita scriva «poemi in vernacolo alto, in una pura,

classica lingua simile all’arabo, al greco, all’ebraico» (O, 135), poemi,

quindi, che scavano in verticale nella storia della Sicilia, «barbarica» (O,

141) al presente. Infatti, mentre Michele Amari ricorda che l’arrivo degli

Arabi «diede risveglio, ricchezza, cultura, fantasia» (O,

- alla Sicilia, Mazara, in

seguito agli aiuti economici ricevuti dal Governo negli anni Sessanta del

Novecento, ha fatto registrare tantissimi casi di razzismo contro Arabi e Neri.

I fatti di cronaca si mescolano così alle memorie del passato, personali e

collettive, dando vita ad un

- Il

particolare significato che Consolo attribuisce a Cefalù è spiegato ne La corona e le armi (La mia isola è Las Vegas, 98-102).

- Qui Consolo ha scritto:

«Questa città è un macello, le strade sono carnezzerie

con pozzanghere, rivoli di sangue coperti da giornali e lenzuola. I morti

ammazzati, legati mani e piedi come capretti, strozzati, decapitati, evirati,

chiusi dentro neri sacchi di plastica, dentro i bagagliai delle auto,

dall’inizio di quest’anno, sono più di settanta» (Le pietre di Pantalica, Milano, Mondadori, 1995, 132).

- Cfr. E poi arrivò Bixio, l’angelo della morte,

in La mia isola è Las Vegas, 103-110.

testo che si

pone «fuori da ogni vincolo di genere letterario».33 Alla letteratura, però,

continua a guardare Consolo. Sono infatti «i racconti scritti di Tomasi di

Lampedusa e quelli orali di Lucio Piccolo di Calanovella» a guidare il

viaggiatore nell’ultima tappa del suo viaggio, un vero e proprio «itinerario di

conoscenza e amore, lungo sentieri di storia» (O, 143). Ancora, tra le macerie

di Gibellina, vede Carlo Levi, sente «le sue parole di speranza rivolte ai

contadini intorno» (O, 144), vede Ignazio Buttitta, Leonardo Sciascia, tutti

scrittori che concepiscono la loro attività in funzione civile. 34 Non sempre, però, i nuovi

tempi lo consentono. Già Consolo si

- chiesto: «Cos’è successo a

colui che qui scrive, complice a sua volta o inconsapevole assassino? Cos’è

successo a te che stai leggendo?» (O, 81). Sotto il segno di una finzione, che

è mezzo per affermare la funzione civile della letteratura, si conclude,

allora, il nostro testo. Consolo immagina che, «sopra il colle che fu di

Gibellina» (O, 148), si rappresenti la tragedia di Masada nell’interpretazione

di Giuseppe Flavio, a suggellare la volontà di difendere i valori autentici del

consorzio civile dall’attacco omologante della società di massa, del degrado

portato avanti da un falso sviluppo tecnologico, incarnato dai romani «con tute

di pelle, […] caschi, […] motociclette» (O, 149):

- Da gran tempo avevamo

deciso, o miei valorosi, di non riconoscere come nostri padroni né i romani né

alcun altro all’infuori del dio… In tale momento badiamo a non coprirci di

vergogna… Siamo stati i primi a ribellarci a loro e gli ultimi a deporre le

armi. Credo sia una grazia concessa dal dio questa di poter morire con onore e

in libertà… Muoiano le nostre mogli senza conoscere il disonore e i nostri

figli senza provare la schiavitù… (O, 148).

«Narra una

voce» (O, 148): solo così, cioè, salvaguardando la propria humanitas, gli uomini possono creare letteratura, la cui funzione

propria è ‘politica’. Consolo lo dichiara esplicitamente:

Ma: cos’è la

letteratura, la narrativa soprattutto, con la sua scrittura in prosa più o meno

di comunicazione, immediatamente o mediatamente, se non politica? Politica nel

senso che nasce, essa letteratura, da un contesto storico e sociale e ad esso

si rivolge? E si rivolge, naturalmente, con linguaggio suo proprio, col

linguaggio letterario (leggeremmo, se no, trattati di storia, perorazioni

politiche, relazioni giornalistiche …). Linguaggio che fa sì che il fatto

narrato sia quello storico, sia quello politico, ma insieme sia altro oltre la

significazione storica; altro nel senso della generale ed eterna condizione

umana. Linguaggio che muovendo dalla comunicazione verso l’espressione attinge

quindi alla poesia. 35

- G. FERRONI, Il

calore della protesta, in «Nuove Effemeridi», VIII, 29 (1995/I), 174.

- Si

evince dalle pagine che Consolo dedica a questi scrittori negli articoli

riuniti in Di qua dal faro e ne Le pietre

di Pantalica.

- CONSOLO, Uomini

sotto il sole, in Di qua dal faro,

229.