38

the simple purpose of the port itself. The same simple modes of communications that Braudel describes may seem irrelevant when studying the Mediterranean history in its entirety, but we get to understand that they are actually the building blocks of the Mediterranean itself:

‘This is more that the picturesque sideshow of a highly coloured

history. It is the underlying reality. We are too inclined to pay attention only to the vital communications; they may be interrupted or

restored; all is not necessarily lost or saved. ‘ 37 The primordial modes of communication, the essential trade and the mixture of language and culture all have contributed to the creation of what we now sometimes romantically call the Mediterranean. The truth lies in the fact that

the harbour has always been prone to receiving and giving back; it has been a passing place of objects, customs and of words. We surely cannot deny the fact that trade has shifted not only by moving from different areas of interest but it also shifted into different forms changing the harbour’s initial function. This basic fonn of communication has contributed highly to the formation of a Mediterranean imaginary and a mixture of cultures that have left a deep resonance in language, literature and cultural expression as a whole.

37 Femand Braudel The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean world in the age of Philip II (Fontana press: 1986) pp.I 08

39

The risk and insecurity delivered by the sea have contributed to the

fonnation of various symbols that from their end contribute to the fonnation of an imaginary concerning the Mediterranean harbour. Amidst the uncertainties and hazards at sea, the light of the lighthouse that shows the surest path and warns the person travelling of the possible dangers, reassures the traveller while leading the way. The symbol of the lighthouse is tied to the representation of light and thus knowledge. Finding light in the middle of the sea gives the traveller the necessary means to have greater awareness of what is approaching. The geographical position and the architecture of the lighthouse are all an indication of their meaning beyond their primary objective. During the Roman period for example, the lighthouse was primarily an important source of safekeeping,38 but at the same time it represented a high expression of architectural and engineering knowledge. One example is the ancient roman lighthouse in Messina. Studies show that the architecture used was very functional, but at the same time it portrayed Neptune, thus mingling popular beliefs and superstitions. On the other hand, it was also a powerful way of delineating borders between Sicily and the Italian peninsula. Today the lighthouse in Messina has been replaced by fort San Remo and the architecture of the lighthouse has changed to a more functional one. Another powerful example is the ancient lighthouse in Alexandria, built on the island of Pharos where it stood alone as if wanting to replace the harbour itself. In Alexandria it is Poseidon who guards

the harbour, and the myth blends with the social and geographical importance of the lighthouse. Originally, the lighthouse in Alexandria was simply a landmark, but 38 Turismo La Coruna, Roman Lighthouses in the Mediterranean (2009) www.torredeherculesacoruna.com/index.php?s=79&l=en (accessed September, 2014)

40

eventually during the Roman Empire, it developed into a functional lighthouse. In the case of the old lighthouse built during the Roman period at the far eastern end of Spain, its dimension and position reflect the way Romans saw the world and how they believed Spain marked the far end of the world. What these lighthouses had in common was the fact that they were not just there to aid and support the traveller in his voyage but to define a border and to give spiritual assistance to the lost passenger. The symbol of the lighthouse is somehow deeply tied to a spiritual experience. In Messina where Neptune guarded the sea, and in many other places and different eras, the lighthouse was positioned in such way that it attracted a spiritual resonance and the light that emanated from the lighthouse may be compared to a spiritual guide. Matvejevic in his Breviario Mediterraneo39 compares lighthouses to sanctuaries and the lighthouse guardian to a spiritual hennit. He also adds that the crews responsible for the running of the lighthouse resemble a group of 1ponks, rather than sailors: ‘Gli equipaggi dei fari, cioe personale che somiglia piuttosto ai monaci dei conventi di un tempo che non ai marinai’ .40 ‘The crews of the lighthouses, that is staff that resembles more the convent’s monks of yore rather than the sailors’. The comparison is by no means striking, considering the mystical importance of the lighthouse. The lighthouse and its crew are seen and respected by the traveller, as they are their first encounter with land, safety and refuge. The link with spirituality is something that comes 39 Predrag Matvejevic Breviario Mediterraneo (Garzanti:2010) pp.55-56 40 Predrag Matvejevic Breviario Mediterraneo (Garzanti:2010) pp.56 41

naturally. The lighthouse crew for example is in some cases part of the ex-voto paintings found in the monasteries and convents. This illustrates the deep c01mection with the spiritual aspect. The question sometimes is to detennine whether the harbour and the lighthouse need to be two distinct features in the same space or whether they are part of the same geographical, social and cultural space. The answer may vary according to the way one perceives it. The lighthouse is the first encounter with land, but it is almost a feeling that precedes the real encounter with land, whilst the harbour is the first physical contact with land. The two elements may be taken into account separately, but for the purpose of this study they need to be taken in conjunction. The cultural value of both these elements goes beyond their physical value. In fact, both the lighthouse and the harbour share a common proximity to the sea, and receive cultural and social contributions from every traveller. The lighthouse and the harbour do not distinguish between different types of travellers -they accept everyone and their main gift for this act of pure love is the enrichment of culture, customs, language and food. The different elements intertwine and create a beautiful atmosphere that mixes sounds and tastes from various countries. This is not always distinguishable and it may not in all cases recreate the same atmosphere

in more than one country. What is sure is that the elements present in the harbours are of great relevance to what is portrayed on a higher artistic and cultural level. In this regard the harbour acts as a lighthouse for the country and sometimes for the region too, this time not to alann the traveller but to guide him spiritually and 42 artistically. The harbour was and still is a meeting place, where artists and thinkers stop and reflect. What comes out of these reflections sets deep roots in the cultural knit of the harbour and expands and grows until all the roots intertwine and create such a beautifully varied cultural atmosphere. Although the process may seem an easy and flowing one, we must not forget that the mixture of cultures and the setting up of such a variegated cultural atmosphere was not always flowing and peaceful. 3.1 Religious Cultural Mobility

The way the Mediterranean is geographically set up, contributed to an

expansion of religious pilgrimages that intertwined with marine commerce and

cultural richness. The image of the lighthouse and the harbour instil a sense of

spiritual refuge, and the large number of harbours and lighthouses in the

Mediterranean contribute to the mysticism of the region. Religious pilgrimage

throughout the Mediterranean is something that belongs to an older era and that

could have possibly started very early in the Greek empire, where Gods were

adored and ports and lighthouses had deep ties with different deities. As

Christianity started spreading in the Mediterranean, the Greek and Roman gods

were joined by saints and shrines for adoration.41 The coexistence of both pagan

and monotheistic religious expressions confinned a cultural motif related to

41 Peregring Horden, Nicholas Purcell The Corrupting sea, a study of the Mediterranean histmy (Blackwell publishing:2011)

43

divinity that has been a constant throughout Mediterranean history. In the Middle Ages the phenomena of the religious pilgrimage and the movement of saints’ relics gave to the Mediterranean voyage a different dimension. As noted in Borden and Purcell’s The Corrupting Sea, this age of pilgrimage and movement for religious purposes was brought about by a new discovery of sea routes in the Mediterranean and a different conception of religion as a c01mnodity. ‘Through the translation of his remains the saint himself, like the images of pre-Christian deities before him, in a very intense expression of the link between religion and redistribution, became a commodity’ .42 The redistribution of relics brought a new type of secular economy that involved bargaining and bartering. The movement of relics not only created a new wave of economic activity around the Mediterranean but also a movement of tales and accounts that pictured saints and voyages at sea, ‘Tales which echo real webs of communication, such as that of the arrival of St. Restitua from Carthage to Ischia’ .43 The stories seem to recall older stories from Greek culture, but are adapted to a newer setting.

The parallelism between good and bad, projected on the perilous voyage in

the Mediterranean, was always part of the account of a voyage itself, as we can

also recall in the various episodes of Ulysses’ journey. We are thus able to see that

in the voyages of pilgrims, the relationship between good and bad is often

projected onto the hard and extreme weather conditions in the Mediterranean.

42 Ibid pp.443

43 Ibid pp.443

44

Religious travellers had their own way of reading the map of the Mediterranean,

interpreting every danger and threat through religious imagery. From a cultural point of view, the accounts and echoes of religious travellers shaped the Mediterranean Sea itself and gave new life to the ports they anchored in. Apart from the movement of relics, another testimony of the great communication and cultural heritage -as we have previously mentioned- is the exvoto in the Mediterranean shores which gives witness to the cultural interaction and

customs based on faith. In many instances the objects collected for the ex-voto

have been taken up over time and placed in marine museums where cultural

interaction and exchange takes place. One example could be the ex-voto in

Marseille,44 where nowadays the objects collected are part of a collective cultural memory. In France, during the late seventies and the early eighties we have seen a great rediscovery of the ex-voto heritage that led to a deep cultural resonance in the area. The discovery of the ex-voto brought by a new inquiry of religious and harbour customs that were probably ignored previously. The paintings and objects dedicated to the saints and most of the time to the Virgin Mary represented the everyday life of sailors and travellers, the dangers at sea and most of all the miracles encountered during the arduous voyages. In the various exhibitions about ex-voto in France the concept of a Mediterranean ex-voto emerged and we are aware that at the time when the ex-voto was practiced in the majority of cases the 44 Jacques Bouillon ‘Ex-voto du terroir marsellais’ Revue d’histoire modern et contemporaine (1954) pp.342-344 45

voyage routes were sole1m1ly around the Mediterranean and the fact that marine exhibitions concerning the ex-voto claim a Mediterranean heritage calls for a collective cultural expe1ience. It is difficult though to distinguish between a

personal encounter with the harbour and a Mediterranean experience; one may

intertwine with the other. In this case, the Mediterranean reference is imposed and not implied, and one might therefore wonder if there are elements that are c01mnon in the region and thus justify the use of the word Mediterranean. In the case of the ex-voto, it has been noted that certain elements are common to the whole region.

It is interesting to note the areas of interest and the social groups to whom

the ex-voto applies. This may give a clearer idea of the criteria and the cultural

sphere that surrounded the practice of the ex-voto. In the majority of cases the exvoto represented the medium bourgeoisie and the lower classes, the setting mostly represented small nuclear families. In most of the ex-voto paintings, one can see that the terrestrial elements intertwine with celestial elements ‘Dans sa structure, un ex-voto presente deux espaces, celeste et terrestre’ .45 The anthropological and cultural importance of the ex-voto emerges through the various figures that appear especially in the paintings dedicated to the saints and the Virgin Mary. These figures have a particular placement in these paintings that reveals a deep connection with the cult of miracles and devotion.

In Malta, as in France, the ex-voto was a widespread custom that left a

great cultural heritage. The paintings and objects donated to the ex-voto, especially 45 Jacques Bouillon ‘Ex-voto du terroir marsellais’ Revue d’histoire modern et contemporaine (1954) pp.342-344 46

in connection to the sea, reveal a number of historical events and geographical

catastrophes that are tied with the Mediterranean region. The fact that the sea is

unpredictable makes the practice of the ex-voto much more relevant in an era

where the only means of transportation in the Mediterranean was by ways of sea. In the Maltese language there is a saying ‘il-bahar iaqqu ratba u rasu iebsa ‘ which literally translates to ‘the sea has a soft stomach but it is hard headed’. This saying is very significant as it shows the profound awareness of the Maltese community of the dangers at sea. The sea is unpredictable and therefore only through divine intercession can the traveller find peace and courage to overcome any dangerous situation. The different types of paintings that were donated portray different types of vessels and so indicate a precise period in history. At the Notre Dame de la Garde in Marseille, one finds a number of models of different vessels from various historical periods. We also encounter very recent models of boats. This confirms that in a way the ex-voto is still present nowadays. Even in Malta, the practice of the ex-voto is still relatively present, although one may notice that the advance in technology and the new fonns of transport through the Mediterranean aided the voyage itself and therefore diminished the threats and deaths at sea. The types of vessels used in the paintings also shows the different modes of economic trading voyages in the Mediterranean. For example, in Malta during the nineteenth century, a great number of merchants were travellmg across the Mediterranean. This resulted in a number of ex-voto paintings that pictured merchants’ vessels and one could be made aware of their provenance. Various details in the ex-voto 47

paintings show many important aspects of the Mediterranean history as a whole

and of the connectivity in the region that went on building through time.

One interesting fact common to almost all the ex-voto paintings is the

acronyms V.F.G.A (votum facit et gratiam accepit) and sometimes P.G.R (Per

Grazia Ricevuta) that categorizes certain paintings into the ex-voto sphere. The

acronyms literally mean that we made a vow and we received grace and P.G.R

stands for the grace received. The acronyms are in Latin, for a long period of time which was the official language of Christianity. These acronyms, which may have indicated the tie of high literature -through the knowledge of Latin- and popular culture -through the concept of the ex-voto, usually associated to a medium to lower class- demonstrate that the use of language may tie the various social classes. Although everyone understood the acronyms, it doesn’t mean that Latin was fully understood amongst sailors and merchants of the sea. Language was a barrier to merchants, traders and seamen most of the time. The Mediterranean has a variety of languages coexist in the region; Semitic languages at its south and Romance languages at its north. The lines of intersection and influence of languages are not at all clear and the geography of the Mediterranean region forced its people to move and shift from one place to another for commerce or for other reasons which brought by a deep need for modes of communication.

48

3.2 The Lingua Franca Mediterranea as a Mode of Communication

The communication barrier between people in the Mediterranean coupled

with the profound need for interaction brought by a deep need of a common

language or at least common signals which would be understood by everyone. In

the case of the ex-voto, language or at least a reference made to a certain language, gives the possibility for people from different countries to understand the underlying message. In the Mediterranean harbours where interaction between people from different lands was the order of the day, the need for common signals and language was always deeply felt. Languages in the Mediterranean region contain linguistic elements that throughout history have been absorbed from other languages. In the Mediterranean region especially during the fifteenth century, the great need for communication resulted in the creation of a so-called Lingua fiw1ca, a spoken language that allowed people to communicate more freely within Mediterranean ports. One such language was known as ‘Sabir’, with words mainly from Italian and Spanish, but also words from Arabic and Greek. The interesting fact about Sabir was that the amount of words coming from different languages around the Mediterranean was an indication of the type of c01mnerce that was taking place at the time. Therefore, if at a given moment in time the amount of words from the Italian language was higher than that from the Spanish language, it meant that commerce originating and involving from Italy predominated. As Eva Martinez Diaz explains in her study about the Lingua ji-anca Mediterranea:

49

‘They created a new language from a mixture whose lexical and

morphological base – the base of pidgin – is the Romance component,

exactly the language of the most powerful group in these relations and

which varies according to historical period. ’46 During the 16th Century, for example, the Lingua franca Mediterranea acquired more Spanish vocabulary, due to certain historical events that shifted maritime commerce. This was also an indication of certain political events that shaped Mediterranean history. When a country invaded or colonialized another, as happened in Algeria after the French colonization, linguistic repercussions were observed. This mostly affected everyday language communication, especially with the simpler and more functional mixture of words and phrases from different languages in ports and the areas around them rather than at a political level. In Mediterranean ports, the need among sea people and traders to communicatee led to the creation of a variety like Sabir. Sabir comes from the Spanish word saber (to know), although, it is mostly noticeable that Italian fonned it in its prevalence.47 Sabir is known to be a pidgin language. A pidgin is a language used between two or more groups of people that 46 Eva Martinez Diaz ‘An approach to the lingua franca of the Mediterranean’ Quaderns de la Mediteranea, universidad de Barcelona pp: 224

47 Riccardi Contini, ‘Lingua franca in the Mediterranean by John Wansbrough’ Quaderni di Studi Arabi, Litermy Innovation in Modern Arabic Literature. Schools and Journals. Vol. 18 (2000) (pp. 245-247)

50

speak a different language but need to have a business relation, and so, need to find a common language or mode of communication. The word ‘pidgin’ is said to come from the Chinese pronunciation of the word ‘business’. The Lingua fi’anca

Mediterranea was a language that started fonning in the Mediterranean throughout the 15th century and continued to shape and change itself depending on where the political and commercial hub lay; Sabir, specifically as an offshoot of the lingua fiw1ca mediterranea, fonned after the 17th century. The first time that reference was made to sabir was in 1852, in the newspaper ‘L ‘Algerien’ in an article entitled ‘la langue sabir. Apart from a few references made to the language, it is quite rare to find sabir in writing because it was mostly used for colloquial purposes, but in some cases it may be found in marine records. When it was actually written down, the lingua franca mediterranea used the Latin alphabet, and the sentence structure and grammar were very straightforward. In Sabir the verb was always in the infinitive, as, for example, in ‘Quand moi gagner drahem, moi achetir moukere’48, that means ‘when I will have enough money, I will buy a wife’. The use of the infinitive indicated a less complex grammar that made it more functional to the user, as it was a secondary language mostly used for commerce. Although Sabir was in most cases referred to as a variety of the lingua franca mediterranea, we perceive that in the popular culture sphere the word Sabir is mostly used to refer to the common and functional language used in MeditelTanean harbours for communication. It is deceiving in fact, because the 48 Guido Cifoletti ‘Aggiomamenti sulla lingua franca Mediterranea’ Universita di Udine pp: 146

51

lingua fi’anca mediterranea, is the appropriate reference that needs to be made

when talking in general about the language used in harbours around the

Mediterranean. On the other hand, if we want to refer to Sabir we are reducing the

lingua fi’anca mediterranea to a definite period of time and almost a defined

territory association. Nevertheless, both Sabir and lingua fiw1ca mediterranea are two different words that express almost the same thing, it is thus important to establish the minimal difference between the two tenns. In arguing that the lingua franca mediterranea refers to a more general language used in the Mediterranean harbours during the Middle Ages and that went on changing and fonning and changing-assuming different fonns according to the harbour and place where it was spoken- we are looking at the language in a broader way. It is undeniable though that Sabir as a reference to a specific language that fonned in Algeria during the 17th century, is most of the time more appropriate to address specific arguments, especially when it comes to popular culture expedients. Popular culture and literature have expressed their interest in the language through expressions such as poems and songs recalling Sabir as a language that managed to mingle more words of different derivation into single cultural spaces. Nowadays, Sabir is no longer used; in fact we notice that English and Chinese are developing into new pidgin languages, understood almost by everyone, especially when it comes to trade and busmess.

In the Mediterranean we have encountered the rediscovery of Sabir in

culture as a language that has a deep cultural value for Mediterranean countries as 52 a whole. One of the examples of the presence of Sabir in cultural expedients is the famous play by Moliere Le bourgeois gentilhomme49 that was represented for the first time in 1967 at the court of Louis XIV. The story was a satiric expression of the life at court, Moliere was well aware of the life at court and he wanted to show that there was no difference between royals and nonnal people, especially with regards to emotions. Moliere associates the Sabir to the foreign Turks that by means of Sabir they managed to communicate:

‘Se ti sabir,

Ti respondir;

Se non sabir,

Tazir, tazir. ‘ 50

The use of Sabir for Moliere indicated a common language understood both by

French and Turks in this case. The fact that Moliere used Sabir, it meant that

gradually the resonance of Sabir could reach out to a different audience, than it’s

main purpose. In this case the meeting place as the harbour was not present but we may perceive that the mixture of cultures and the need for communication led to the use of Sabir as the common language. 49 Moliere, le bourgoise gentilhomme www.writingshome.com/ebook _files/l 3 l .pdf

50 Moliere, le bourgoise gentilhomme www.writingshome.com/ebook _files/13 l.pdf pp.143

53

Coming to the present day, it is difficult to say that Sabir or the lingua

franca mediterranea own a particular important space in the cultural sphere or in the language per se. We are mostly sure that in the Mediterranean harbours Sabir has no relevance anymore, nevertheless, we find the use of Sabir in popular culture. One example is the aiiist Stefano Saletti,51 who in his songs uses Sabir. Its use was obviously intentional. Saletti looked at the new uprisings in the North African countries and he could recall the same feelings, faces and atmosphere that southern European countries went through thirty years prior. With this in mind, he decided to use a language that had co1mnon elements to all Mediterranean languages, and so he chose Sabir. His albums are inspired by the notion of music and culture as a tie to the whole Mediterranean, being conscious on the other hand of the numerous contradictions and differences in the Mediterranean region. The CD Saletti and the Piccola banda ikona explain what Sabir is and why they chose this language to communicate a c01mnon message through the music: ‘Once upon a time there was a tongue shared by the peoples of the Mediterranean. This was Sabir, a lingua franca which sailors, pirates,

fishennen, merchants, ship-owners used in the ports to communicate

with each other. From Genoa to Tangiers, from Salonika to Istanbul,

from Marseilles to Algiers, from Valencia to Palenno, until the early

decades of the twentieth century this kind of sea-faring “Esperanto”

developed little by little availing of tenns from Spanish, Italian,

51 Stefano Saletti www.stefanosaletti.it/schede/ikonaeng.htm (accessed July, 2014)

54

French and Arabic. We like this language. We like to mix sounds and

words. We play Sabir. We sing Sabir.’ 52 The importance of Sabir for Saletti shows that the harbour’s cultural value has been transmitted through time. Does the use of Sabir by Saletti indicate a recreation of a language that was used in the harbour as a functional and common means of communication or does it have the pretext to artificially recreate a common language? It is difficult to understand the importance and relevance an old pidgin language used for a specific purpose might hold today. Nevertheless, the use of this specific language in the music of Saletti reveals a profound search for common cultural traits in the Mediterranean region, that in this case aim to opt for cultural and educational approach to unite a region that is fractured in its own

basis. Saletti refers to Sabir as resembling Esperanto; a failed attempt to

linguistically unite a region that cannot be united. Although we may find the same concept in Esperanto and Sabir, we are aware that they differ in the way they came to be. Esperanto was artificially constructed, whereas, Sabir was born and evolved in an almost natural way by a need that went beyond the actual artifice. This is probably the reason why Sabir and the lingua franca mediterranea lasted for a long period of time, while Esperanto was at its birth a failed attempt to create a language for a detennined sector in society. It is a fact that the main difference between the two languages is that one aimed to create a broader understanding based on a functional everyday life need, whereas the other aimed to create a 52 Stefano Saletti www.stefanosaletti.it/schede/ikonaeng.htm (accessed July, 2014)

55

language understood by few. In Saletti’s and Moliere’s works, we perceive the Mediterranean harbour as a point of intersection of cultures and ways of living that left a spill-over of cultural traits in the abovementioned artistic works and in many other works by various authors around the Mediterranean region. It is important to notice that the harbour in the expression of the ex-voto, Sabir, lingua franca mediterranea and various literal and artistic expressions, served almost as a lighthouse, where culture was projected and created, and recreated and changed to fit the ever changing needs of the Mediterranean differing cultures. In Jean-Claude Izzo’s Les Marins Perdus, the language used in the harbour is not mentioned often, although he refers to language

as a barrier that finds its purpose in the basic everyday needs. Jean-Claude Izzo

mentions an important point on language in Les Marins Perdus as he delves in the way the word ‘Mediterranean’ is seen in different languages across the region: ‘Il Mediterraneo e di genere neutro nelle lingue slave e latine. E in

maschile in italiano. Femminile in francese. Maschile e femminile in

spagnolo, dipende. Ha due nomi maschili in arabo. E il greco, nelle

sue molteplici definizioni, gli concede tutti I generi. ‘ 53

‘The Mediterranean is neutral in the Slavonic languages, and in Latin.

It’s masculine in Italian. Feminine in French. Sometimes masculine,

sometimes feminine in Spanish. It has two masculine names in Arabic.

53 Jean-Claude IzzoMarinai Perduti (Tascabili e/o: 2010) pp.237

56

And Greek has many names for it, in different genders.’ Jean-Claude Izzo wants to prove that the word ‘Mediterranean’ in language is a sufficient proof of how people around the shores view the region. The gender of the word Mediterranean does in fact show that the languages in the region have

developed their own way of understanding and perceiving the region. Language as we have seen has deep ties to how popular culture and ideas have evolved and

developed. Sabir in its essence has proved that although the region has a myriad of contradictions and differing cultures, the harbour and everyday needs managed to combine the different languages into one. At the same time it is undeniable that the differences in the Mediterranean region make the region itself not only vast but also wonderful and enticing to the traveller and the artist. Literature and culture have fonned and mingled together, yet each maintained its distinct features at the the Mediterranean harbours; the place of various particular encounters. Jean Claude Izzo, Salletti and Moliere all managed to create a powerful work of art that has deep ties to the culture created and recreated over time in the Mediterranean harbours. Sabir and the ex-voto are only two examples of how harbours throughout

the Mediterranean have been a point of anchorage but also a locus of

Mediterranean cultural development. Harbours have been able to unite, divide and create such a diverse and yet common culture.

57

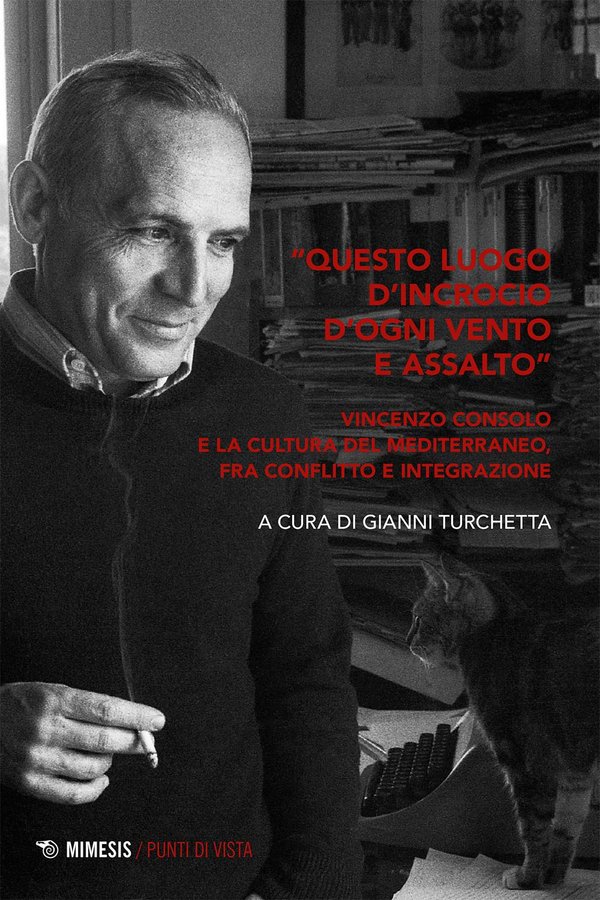

4 The Mediterranean Imaginary of Jean-Claude Izzo and Vincenzo Consolo Inspired by the Port The Mediterranean as a discourse has been interpreted and reinterpreted, and idealized and mystified by a myriad of authors, thinkers and artists. In this modem era where globalization of thought is the nonn, the Mediterranean discourse is by far a difficult expression that finds obstacles in the concretization of its own thought. Nevertheless, today the Mediterranean is still capable of producing new artists and new expressions by which the discourse gets richer and deeper. The Mediterranean, as its name suggests, is a sea that is in between two lands, and as Franco Cassano 54 states, has never had the ambition to limit itself to only one of its shores. The Metlitenanean was fm a periotl of time consecutively and simultaneously Arab, Roman and/or Greek; it was everything and nothing at the same time. The Mediterranean never aspired to have a specific identity, and its strength lies in its conflicting identity; it embraces multiple languages and cultures in one sea. Franco Cassano in his L ‘alternativa mediterranea states that borders are always ahead of centres, ‘Il confine e sempre piu avanti di ogni centro’55, and this concept is very relevant when we think about the significance of the harbour, as a place at the border of the country and yet the centre of every interaction.

Cassano goes on explaining how the centre celebrates identity, whereas the border is always facing contradiction, war and suffering. The border cannot deny the suffering by which the conflicting and inhomogeneous Mediterranean identity has 54 Franco Cassano, Danilo Zolo L ‘alternativa mediterranea (Milano: Feltrinelli, 2007) 55 Franco Cassano, Danilo Zolo L ‘alternativa mediterranea (Milano: Feltrinelli, 2007) pp.80

58

been built upon. The border is the true expression of the Mediterranean and it is

undeniable here that the most important interactions and historical events in the

region have taken place.

The border is an important concept in the study of the Mediterranean

itself, and as already mentioned, the majority of intersection and cultural

exchanges have taken place in the harbours, which are the borders of a country yet the centre of every interaction. For the concept of a ‘Mediterranean identity’ to arise, the harbour has been a pivotal place economic and religious interactions

which consequently left an undeniable cultural baggage whose strong presence

allowed the Mediterranean shores to benefit from an enriching cultural melange.

Being a sea of proximity, the Mediterranean has always been prone to receive the

‘other’ with all its cultural baggage, and therefore the concept of fusion and

amalgamation of different aspects of every country has always contributed to the

region’s culture. Accounts about the Mediterranean and those set in it have always put at their centre the concept of ‘differences’ and the ‘other’ in contraposition to the conflicts found in the harbours and in its centres. Nevertheless, without expecting the ends to meet to a degree of totality, the Mediterranean has been able to create places where ends do not merely meet but coexist. The coexistence of different races, cultures and languages has been the founding stone of the region.

As Cassano states, an identity that claims to be pure is an identity that is destined

to fail because it is in the essence of a culture that it repels the ‘other’, and

therefore sees the answer to every problem in the elimination of the ‘other’. The

59

Mediterranean, on the other hand has embraced ‘the other’ or on occasion, ‘other’ has forcedly penetrated the Mediterranean, giving birth to a region of different cultures based on a coexistence which is sometimes peaceful but often hard. The Mediterranean nowadays has overcome the complex of Olientalism and moved forward from a vision of an exotic south or border; ‘non e piu una frontiera o una barriera tra il nord e il sud, o tra l’ est e l’ ovest, ma e piuttosto un luogo di incontli e correnti … di transiti continui’ .56 ‘it is not a border or bamer between North and South, or East and West anymore, but it is rather a place of encounters and trends of continuous transits’. The Mediterranean has become a region of transit and a meeting place.

Upon travelling across the Mediterranean, an important thing which makes

itself evident is the imaginary that keeps on building through the interaction

between authors and thinkers, especially through their works that focus on the

importance of stating a discourse about the Mediterranean.

4.1 The Mediterranean Imaginary in Izzo and Consolo

‘Il Mediterraneo none una semplice realta geografica, ma un temtorio

simbolico, un luogo sovraccalico di rappresentazioni. ’57

56 Franco Cassano,Danilo Zolo L ‘alternativa mediterranea (Milano: Feltrinelli, 2007) pp.92 57Jean-Claude Izzo,Thierry Fabre Rappresentare il Mediterraneo, Lo sguardo francese

(Mesogea: 2000) pp.7

60

‘The Mediterranean is not a simple geographical reality, but a

symbolic territory, a place overloaded with representations.’

The Mediterranean is a region full of symbolism and representationswhich

would not exist if it were not supp01ied by the literature and culture that has

fonned on and around its shores. The Mediterranean as a region of imaginaries

built on the integration of different voices and stories has produced a number of

authors and thinkers that left a cultural and artistic patrimony to the discourse

about the Mediterranean. We have already seen how the harbour transmits a sense of insecurity and plays a role of threshold which is testified through the works of Izzo and Consolo. Both authors have not only shown the importance of the harbour but have also contributed arduously to the fonnation of a Mediterranean imaginary. The word imaginary, comprehends a number of images, figures and fonns that are created by the observers to define something -not solemnly by the mere reflection of facts and historical events, but by a personal evaluation- that sometimes goes beyond reality. In this sense, it is undeniable that the Mediterranean has gathered a number of observers who have been able to translate facts and create figures and images that represent a collective in a singular imagination. Consolo and Izzo have transfonned their personal encounter with the Mediterranean into a powerful imaginary.

Jean-Claude Izzo was born and raised in Marseille in a family of Italian

immigrants. His background and geographical position highly influenced his

61

writing. Both Izzo and Consolo shared a deep love for their country of origin

especially for the microcosm surrounding them. Vincenzo Consolo wrote about

his beloved Sicily, while Izzo always mentions Marseille. Both authors transpose

the love for the microcosm into a broader vision of the Mediterranean as a whole.

Jean Claude Izzo’s Mediterranean is based on a passionate encounter with the

region and states that his Mediterranean differs from the one found at travel

agencies, where beauty and pleasure are easily found.

‘Cio che avevo scoperto non era il Mediterraneo preconfezionato che

ci vendono i mercanti di viaggi e di sogni facili. Che era propio un

piacere possibile quello che questo mare offriva.’ 58

‘I had discovered a Mediterranean beyond the pre-packaged one

usually sold and publicised by Merchants, as an easy dream. The

Mediterranean offered an achievable pleasure.’

The Mediterranean hides its beauty only to reveal it to anyone who

wants to see it. The Mediterranean for Izzo is a mixture of tragedy and pleasure,

and one element cannot exist without the other. This image of beauty and

happiness shared with tragedy and war is a recurring one in the study of the

Mediterranean. Consolo’s writing is based on the concept of suffering. He

pictures human grief and misery as an integral part of the Mediterranean

58 Jean-Claude Izzo, Thierry Fabre Rappresentare il Mediterraneo, Lo sguardo francese (Mesogea:

2000) pp.17

62

imaginary and he feels that poetry and literature have the responsibility to transmit the human condition. Izzo in his writings not only shows that the Mediterranean imaginary is made up of tragedy, suffering and war but also shows that there is hope in the discourse about the Mediterranean itself. For Izzo, the Mediterranean is part of his future, part of his destiny, embodied in the geography of the region and in the tales and accounts that inhabit every comer of the region. Through his beloved Marseille, Izzo manages to look at the Mediterranean and thus find himself.

The word ‘imaginary’ in the academic sphere is tied to a concept used

for the definition of spaces, a definition that goes beyond the way things seem

externally, a definition that puts much more faith in how an author, thinker or

artist expresses and describes the space. In the case of the Mediterranean, since

the region is not an officially recognized political entity, identity is based on

interpretation more than anywhere else and the concept of an imaginary proves

that there are paths that still lead to thought about the Mediterranean. With this in mind, one cam1ot deny the fact that in the political or social sphere, the concept of Medite1Tanean is still being mentioned; however, one could argue that the Mediterranean that is being mentioned in a political and social sphere is somehow a constructed ‘Mediterranean’. The Mediterranean’s relevance nowadays is found in the hearth of the author and artist that from Tangiers or from Marseille is able to write about a sea that has thought him to be mobile, to travel not only physically but mentally and emotionally from one shore to another. Jean-Claude Izzo’s troubled identity gives us a hint of the way in which the Mediterranean is 63

perceived as a region and the way in which the personal ‘imaginary’ for Izzo was

fonned. Izzo himself was from a family of mixed origins and was raised in a

constant state of travel. Izzo found his Mediterranean identity in the imaginary

other authors had created but also found his roots in the very absence of more

organic roots. Every story and every country may be part of his own identity, and

so, the Mediterranean has the ability to preserve in the depths of its sea the stories and feelings collected from every shore and give a curious traveller the

opportunity to retrieve these treasures and make them his own.

The historical approach to the Mediterranean has been based on a

comparison between south and north, between the Mediterranean and Europe, and it usually focused much more on the contrasting elements than on its conjunctions and similarities. Braudel59 saw the Mediterranean as a static and unchanging region. Today, modem thought has led to a new perception of the Mediterranean, focusing rather on the points of conjunction than on the differences and contrasting elements, yet accepting the fact that the Mediterranean is diverse in its essence. In a paper by Miriam Cooke about the Mediterranean entitled Mediterranean thinking: from Netizen to Metizen60

, she delves into the importance of the juxtaposition between the liquidity of the sea and the immobility of the land in the rethinking process of the Mediterranean. In the Mediterranean imaginary, the sea serves as a mirror and as a fluid that is able to connect and remain welldefined.

It is able to give a sense of time that is very different from the one on

59 Femand Braudel The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean world in the age of Philip II (Fontana press: 1986) 60 Miriam Cooke ‘Mediterranean thinking: From Netizen to Medizen’ Geographical review, vol 89 pp.290-300

64

land. As we perceive in Jean-Claude Izzo, time is something that is completely

lost at the border between sea and land and especially in contact with the sea.

Sailors in Les Marins Perdus61 realize the concept of time only when they live in

the harbor and in other words, the sea has been able to preserve the sailor’s spirit in the illusion that time on land was as static as it was at sea. In the study about the Mediterranean region, the sea plays a fundamental role that must not be underestimated. Jean-Claude Izzo and Vincenzo Consolo both refer extensively to the figure of the sea when addressing the Mediterranean imaginary. When pondering on the Mediterranean, Izzo always places himself facing the sea, embracing the liquidity of this region, whereas in his stories, Consolo always uses the sea as the main mode of transportation and giving it a mystical attribute.

The Mediterranean has a different meaning for the two authors, because

it is perceived from two different places and two different conceptions of the

Mediterranean arise. In much of Consolo’ s writing, the Mediterranean is seen

through the image of Odysseus which is an image that holds a special meaning for Consolo and to which he feels deeply tied. For Consolo, The Odyssey is a story

that has no specific ending and this is done on purpose because it is directly tied to the future. The door to the future was kept open with the specific purpose of

letting the figure of Odysseus trespass time. The importance of Ulysses in

Consolo’s discourse extends to a deep and personal search for identity and it is

identity itself and the search for knowledge that led Ulysses to embark on a

61 Jean-Claude Izzo Marinai Perduti (Tascabili e/o: 2010)

65

voyage around the Mediterranean region and afterwards to return to Ithaca. Like

Izzo, Consolo finds the essence of a Mediterranean imaginary in the act of

travelling and sometimes wandering from coast to coast, from harbour to harbour, somehow like a modem Ulysses that aims to find himself and find knowledge through the act of travelling and meandering. Many authors that have focused their attention on the figure of Ulysses have focused on Ulysses’ return to Ithaca in particular and the search for a Mediterranean identity through this return.

Consolo, however, mainly uses the metaphor of travel and wandering, and he

manages to tie them to the question of a Mediterranean imaginary that is being

built upon the various images that the author is faced with through his voyage. For Consolo the voyage and the constant search for knowledge are the founding

stones of a Mediterranean imaginary. This urge to push further and thus reach a

greater level of knowledge has driven the Mediterranean people to practice

violence, and therefore Consolo believes that violence tied to the expression of a

deep search for knowledge is what has constituted the Mediterranean region. In

L ‘Olivo e L ‘Olivastro 62

, Vincenzo Consolo uses Ulysses’ voyage as a metaphor of his own voyage and his personal relation with Sicily; being his homeland it holds

a special place for Consolo especially in his writings. Constant change in the

modern concept of a Mediterranean has left a deep impact on the Mediterranean

imaginary. The wandering Ulysses returns to a changed and metamorphosed

Ithaca, which is a recurring image in the Mediterranean. Consolo finds his home

62 Norma Bouchard, Massimo Lollini, ed, Reading and Writing the Mediterranean, Essays by Vincenzo Consolo (University of Toronto Press, 2006)

66 island ‘Sicily’ deeply changed by industrialization and although it may have

maintained features that recall the past, it has changed greatly. Images of the

harbour and of the Mediterranean itself have deeply changed. Change may be

positive, negative or may hold a nostalgic tone, although change is always a

positive factor that contributes to the fonnation of an ‘imaginary’. The way

Ulysses and authors such as Consolo and Izzo have wandered and fought their

battles in the Mediterranean has contributed to the change that we now perceive in the region. Through the voyage of Ulysses, Consolo gives testimony of the

Mediterranean violence and change to the rest of the world. For Consolo the

imaginary created around the Mediterranean is a mixture of his own reality such

as a modem Sicily devastated by industrialization and modernization, and the

recurring image of Ulysses. In fl Sorriso dell ‘Ignoto Marinaio, Consolo focuses

on the microcosm of Sicily as a metaphor of the larger Mediterranean. His

imaginary is characterized by the concept of conflict – a conflict that keeps on

repeating itself in the Mediterranean and is somehow tied to a general conception of the Mediterranean. The harbour acquires an important space in the novel, being the hub of the whole story. The violence mentioned in the novel is a projection of violence in view of an attempt at unifying two different spheres, in this case the unification of Italy, but in a broader sense the possible unification of a Mediterranean. The attempt is not only a failure but results in a continuous war to establish a dominant culture rather than a possible melange of cultures that manage to keep their personal identities.

67

Izzo on the other hand wrote about the Mediterranean imaginary from

the point of view of sailors, who construct a Mediterranean imaginary based on

the concept of a difficult intercultural relationship and a strange bond with the

Mediterranean harbour. In Les Marins Perdus, the microcosm of Marseille

managed to represent the macrocosm of the Mediterranean, and the figures of the sailors represents a modem Ulysses, with the aim of bringing about a

Mediterranean imaginary that mingled old and traditional conceptions of the

region with new and modem ideas. Jean Claude Izzo’s sailors had different ways

of perceiving the Mediterranean, but they had a similar way of seeing and

identifying the ‘sea’. Izzo’s protagonist, much like Consolo’s protagonist,

develops an interesting habit of collecting old Mediterranean maps. For the sailor, the collection of maps represents in a certain way the concretization of a

Mediterranean and the unification of the geographical conception of the region.

The act of collecting may be considered as an attempt at identifying something

that is common, something that is part of a collective memory.

The works of Consolo and Izzo are the literal expressions of a

Mediterranean imaginary, based on their personal encounter with the region and

on their individual research on the subject. The way in which literal texts shape

our conception and ideas with their powerful imagery proves that the personal

encounter becomes a collective encounter in the translation of facts that each

author perfonns in his writings. However, what is most fascinating is the meeting

of ideas brought about through writing which also share elements with popular

68

culture. In essence, popular culture manages to reach a higher audience but it

often takes inspiration directly from literature and its various expressions. In the

sphere of popular culture one may see that the concept of adve1iising and of

mixing various means of communication to reach a specific goal come into action.

Popular culture comp1ises various levels of cultural and artistic expression, and is therefore well placed to reach a larger audience and to imprint in the audience

various powerful images related to the subject chosen. In this case, the

Mediterranean has collected a large amount of popular culture expressions that

managed to create a knit of ideas and interpretations that succeed in intertwining and creating ideas through the use of old traditions and seminal literal texts.

4.2 The Mediterranean Imaginary in Popular Culture

The way in which the Mediterranean has been projected in the sphere of

popular culture owes a lot to the dichotomy between sea and land, between a fixed object and a fluid matter. The fascination around the two contrasting elements managed to create an even more fascinating expression of popular culture, thus an idea about the region that is based on the way in which Mediterranean people view the sea and view the stable and immobile element of land. Moreover, the Mediterranean popular culture focuses a lot on the element of the harbour, a place where the two elements of water and land manage to intertwine, meet, discuss ideas and at times fight over who dominates. The conflict between the two elements, projected in the geographical distribution of the region, has deep 69 resonance in the emotional encounter with the region. Thus, the authors, artists and travellers are emotionally part of this dichotomy that is consequently reflected in their artistic expressions.

To talk about the Mediterranean nowadays is to reinvent the idea behind

the region in an innovative and appealing way. Culture and literature are new

means by which we re-conceptualize the region. The Medite1Tanean has been

compared to the Internet, because it is a place where near and far are not too well defined, where space is something fluid and where infonnation and culture are transmitted through a network of connections. In her study, Miriam Cooke63 notes how even the tenninology used on the Internet derives from marine tenninology.

One example could be the ‘port’ or ‘portal’. In relation to the web, it is defined as

a place of entry and usually signifies the first place that people see when entering

the web. Although virtually, the concept of harbour remains the first and most

relevant encounter a person makes when approaching a country or ‘page’ on the

internet. Although air transportation has gained a great deal of importance,

shipping networks used for merchandise are common and still very much in use.

The parallelism between the Mediterranean and the Internet opens a new way of

conceptualizing the Mediterranean as a physical and cybernetic space. Miriam

Cooke explains how the Mediterranean itself, just like the Internet, changes the

traditional concept of core and periphery: 63 Miriam Cooke ‘Mediterranean thinking: From Netizen to Medizen’ Geographical review, vol 89 pp.290-300

70

‘The islands that are geographically centered in the Mediterranean are

rarely centers of power; rather, they are crossroads, sometimes sleepy

but sometimes also dangerous places of mixing, where power is most

visibly contested and where difficult choices must be made.’ 64

The way in which the Mediterranean is seen geographically most of the

time does not appear to be consistent with the actual function and thought of the

place. As in the case of the islands in the Mediterranean, their main function lies

in the fact that they are crossroads rather than real centres. Usually, the

geographical centre of a country is the actual political, social and economic

centre, however, in the Mediterranean, the centre is where ideas are fonned, and

this usually lies in the harbours and in the cities located in close proximity to the

sea. The centre and marginality of a place according to Cooke depends on the

position of the viewer. Therefore, the explained and conceptualized Mediterranean may have different centres and borders depending on who is writing about it. The function of popular culture is to somehow give a view on where the centre is and where the margins lie.

When discussing the Mediterranean in advertisements and in the media

m general, there is a tendency to start from the past, from a presumed

Mediterranean origin that seems to tie the whole region. In this assumption, there is no truth but just a commercial way of proposing the historical elements that 64 Ibid pp.296 71

unite the region, therefore making it appealing at a touristic level. The audience at times does not have a precise idea of the differing elements and cultures residing in the region. To make it more appealing and coherent, especially in advertising, culture seems to be portrayed as a feature that holds similar elements that recur throughout the region. Even tastes and sometimes sounds seem to be homogenized tlu·oughout the region. The French documentary film entitled Mediteranee Notre Mer a Taus produced by Yan Arthus-Bertrand for France 2, aims to give an overview of the Mediterranean by focusing not just on the common features, but most of all on the fascination of the differences. The

documentary film traces how the Mediterranean has transfonned and shifted over time and it aims to show the deep cultural heritage it left in Europe. Rather than an advertisement or promotional video, this is an educational movie that rotates around the Mediterranean to explain each and every place while delineating its features and importance. The interesting fact about the movie is that it is filmed from above, giving almost an overview of the region, and that it talks about a Mediterranean future that ultimately lies in a supposed c01mnon past. When advertising a harbour in the Mediterranean, most of the short clips focus on the multiculturalism of the harbour and the projection of the place within a broader Mediterranean vision.

72

A particular advertising video, promoting Tangier65 as a harbour city

that looks onto the Mediterranean but remains predominantly African, focuses on the emotions that it can deliver and on the particular features that can attract the tourist such as traditional food and music. In everyday life, certain music and

traditional food would have probably disappeared, but in the projection of a place that needs to attract the tourist, the sensational aspect prevails and the tradition needs to be prioritized. In all the movies concerning advertisement of the Mediterranean harbours, what prevails is the conception of the harbours as

crossroads, as places where cultures meet, and obviously leave deep cultural

heritage. The movement of people in these short clips is shown as a movement

that has brought richness and cultural heritage to the country, ignoring the

ongoing debates about migration. These clips tend to ignore the ongoing problems in the Mediterranean and this is obviously done to increase tourism and project a nicer image of the region, succeeding in having a positive impact on the mind of the viewer.

Another peculiarity that is noticeable both in the clips about the

Mediterranean harbours and in many movies and stories is a concept of time

which is very different from reality. In short clips, such as the one portraying

Tangiers or the one promoting Valletta, it is noticeable that time slows down. In

the transposition of the novel Les Marins Perdus into a movie66, the concept of

65 Fabounab,Tangiers, port of Aji-ica and the Mediterranean (uploaded May, 2010) www.youtube.com/watch?v=E_IJ3zmxC6g (accessed July, 2014)

66 Les Marins Perdus, Claire Devers (2003)

73 time is a fundamental element, because it drastically slows down. The first scene opens up with the overview of the Aldebaran, the ship on which the story unfolds.

This scene is a very long scene that gives the viewer a hint of approaching trouble, from sea to land. It achieves this in a very calm and slow way. Throughout the movie the sense of time being slower than usual is something that finds its apex in the last minutes of the movie when all the tragedies unfold. The way in which the Mediterranean is described in short clips and in this movie shows a common perception of the Mediterranean people as a people who enjoy life at a slower rhytlnn, although in certain cases it might be true that this assumption lacks accuracy. Although it is undeniable that the juxtaposition between land and sea which we especially perceive in the harbour gives a sense of time as a rather fictitious concept, one may recall the Odyssey, where the voyage in the Mediterranean took an unusually long time. The Odyssey in fact bases on the fact that time almost seemed to have stopped and in fact, the time span that Odysseus spent travelling at sea does not match with the actual time that was passing on land in Ithaca. On the other hand we perceive that time is passing by rather slowly for Penelope who patiently raised her son and safeguarded Ithaca while waiting Odysseus.

What the concept of time in the Mediterranean proves is that the various

images that one finds both in writing and in new popular culture are constantly fed to our conception of the region and through time these various concepts fonn an imaginary. In many cases, when we look at popular culture we find elements that 74 we can reconnect to literature. This proves that the means by which an imaginary is constrncted is based on different elements but usually one may find recmTing elements both in popular culture and literature. In the concept of time we also find a common way of seeing life itself. Time in the Mediterranean seems to be stuck therefore we may argue that literature and popular culture have contributed to the fonnation of our ideas about life per se, whilst obviously not denying that everyday life was of constant inspiration to literature and culture. The way in which both popular culture and everyday life intersect, connect and find common points is something of fundamental importance in the study of the Mediterranean imaginary, as it gives different points of view and visions of the subject and therefore creates an imaginary that manages in a subtle way to unite what seems so distant. Jean-Claude Izzo, Vincenzo Consolo and many other authors, as well as different ‘texts’ of popular culture, create an ethos about the Mediterranean that aims to join what appears separate. The fact that nowadays the Mediterranean is still present in popular culture, as in the case of the previously mentioned film shown by France 2, proves that discourse about the region and the Mediterranean imaginary are still alive and they have a presence in the mind of the receiver.

The imaginary of the Mediterranean harbour is also constrncted by the

way it is advertised. A short, recent videob1 advertising the Maltese harbour

repeatedly used the word ‘Mediterranean’ to highlight the connection between

67 Valletta Waterfront, Valletta Cruise Port Malta- the door to the Mediterranean, (uploaded February, 2012) www.youtube.com/watch?v=FMThbEG95WA (accessed May, 2014)

75

Europe and Africa. The way in which the harbour is projected in the French

movie shows a deep connection to the historical and cultural heritage of the

country but it also aims to show how historically and culturally varied the country is. The advertisement’s aim was to create a sense of uniqueness whilst focusing on the broader vision of the Mediterranean as a whole. On the one hand it focuses on the fact that Malta is part of the European Union, therefore boasting high standards of security and maritime services, and on the other hand it promotes the various hist01 ical influences on Malta and its Grand Harbour and portrays it as the gateway both to the northern and to the southern shore. Being an island in the Mediterranean gave Malta the possibility to create its uniqueness, but also to affiliate itself to both Europe and Africa. In this sense, the sea serves as a unifying factor but at the same time it was always able to maintain the individuality of each place. The discourse about the Mediterranean is rendered possible thanks to the various factors that inhabit the region – factors that may differ from one shore to another, thus making the region a more interesting one to study.

4.3 Conclusion The discourse about the Mediterranean has always revolved around the projection of different images that supposedly recall a common feeling and common grounds. The Mediterranean is a region that is in essence a combination of a myriad of cultures; this factor is very relevant in the discourse on the region 76 as the attempt to unite the region in one cultural sphere is somehow a failed attempt. It is relevant to mention that in the production of literature and culture, these different expressions especially concerning the Mediterranean have produced a knit of sensations and feelings that are now mostly recognized as being ‘Mediterranean’. The harbour in this case has always been the locus of the Mediterranean imaginary because sea and land meet in the harbour, and therefore many cultures meet and interact in the harbours.

Harbours are places that live an ‘in between’ life but that still manage to

mingle the differences in a subtle way that feels almost nonnal and natural. The

harbour has inspired many authors as it has built a sense of awaiting and hope in the person. The Mediterranean port seems to suggest that everything is possible, and that imageries and ideas can unfold in the same harbour.

77

5 Conclusion

The Mediterranean city is a place where two myths come together: the

myth of the city and the myth of the Mediterranean. Both myths have developed

independently because both managed to create symbols and connotations that

have been able to survive till today. The myth of the city in relation to the myth of

the Mediterranean has been for a long time regarded independently and therefore it created a succession of elements that was able to reside in the same place but was in essence two different elements. 68

From antiquity, the ‘city’ has been seen as a symbol of social order – as a

place where reason and civilization reign in contrast with the ignorance of the

outskirts. The concept of a ‘city’ that is able to unify ideals and control society by

maintaining high levels of education and increasing cultural standards has

developed a division between the rural areas and the city itself. In conjunction

with the harbour, the concept of a civilized ‘city’ mingles with the idea of a

cultural mixture that is able to absorb what the sea has to offer.

In the Mediterranean port cities, the cultural emancipation and the centre

of trade and business in a way managed to intenningle with the idea of ‘squalor’,

most of the time being associated to the harbour. Nevertheless, in the

68 Georges Duby Gli ideali de! Mediterraneo (Mesogea 2000) pp.83-100

78

Mediterranean harbour cities, the idea of cultural richness and emancipation was a concept that found concretization in the idealization of the ‘city’ itself by its

inhabitants. The ‘city’ as much as the Mediterranean itself found deep resonance

with the growth of literature. In the case of the ‘city’, various treaties and

literature expedients that promoted it as a centre of cultural riclmess and

architectural rigor helped the ‘city’ itself to find a place in the mind of the person

approaching it. The obvious consequence of this new fonnation of cities as a

symbol of 1igor and proliferation was that a great number of people migrated from the rural areas to the cities. The myth of the harbour cities as being the centre of business and a locus of culture went on cultivating with the accounts about these cities written by various authors. They managed to give life to a succession of images that are now imprints of harbour cities throughout the Mediterranean.

The Mediterranean appears unified in anthropological69 discourse in which

assumptions are made about the way ‘Mediterraneaninsm’ is constituted and the

‘Mediterranean way of life’. A group of cultural anthropologists aimed to view

the Mediterranean as a whole for the purpose of identifying elements that

managed to tie the region and gave meaning to the unification itself. On the one

hand they managed to give international relevance to studies about the region

because they constructed what they regarded as common Mediterranean attributes.

On the other hand they were constructing a discourse that said more about their

own vision than about a region that is varied in its essence. In a way they also

69 Georges Duby Gli ideali de! Mediterraneo (Mesogea 2000) pp.83-100

79 rendered the region ‘exotic’. The way in which anthropology managed to create an idea about the Mediterranean is interesting even though a person living in the region might argue that the picture given is incorrect. In this sense the imaginary of the Mediterranean projected by literature does not aspire to give a detailed account of life in the region but rather to actually transmit the feelings and passions that the region has. In this sense, literature was able to transfonn a passion and a detailed account of one’s own perspective about the region into an imaginary that is in its turn able to remain imprinted in the person’s conception of the Mediterranean. Literature and art in the Mediterranean had the ability to prove that there are common feelings in the region but they are distinguishable in their very essence and the harbour with its strategic position was able to give inspiration to the artist that approached it. The creation of an imaginary about the Mediterranean goes beyond the very need of knowing and apprehending facts that may be or may not be common to the whole region. In this sense, the artistic expedients and the literal world managed to relate to the reader and the spectator in a very special way by creating powerful images that construct society.

5.1 The ‘imaginary’ of the Mediterranean

One important definition of the ‘imaginary’ is given by Castoriadis in his

The Imaginary Institution of Society 70 in which he states that the human being

cannot exist without the collective and that the collective is fonned by different

7° Kostantino Kavoulakas Cornelius Castoriadis on social imaginaiy and truth(University of Crete, September 2000) pp.202-213

80

elements. One of the elements that is of great importance in the fonnation of the

collective is the symbol. The symbol or the collection of symbols is fonned from

reality and from an imaginary. In the composition of the imaginary, whatever

stems from reality and whatever stems from fiction remains in essence a question which is not resolved or which probably does not intend to be resolved. Therefore, the imaginary explained by Castoriadis gives a social meaning to certain questions that are fundamental in the complexity of reality. For example, the symbol of God was created for various reasons but its creation per se does not distinguish between elements that are true in its essence and elements that are imagined. The example given by Castoriadis on the symbol of God leads us to the conception of the Mediterranean region as a region fonned in its imaginary by reality and myth which intertwine and are not distinguishable. The Mediterranean created by the various authors and artists mentioned reinforces the imaginary that has at its basis the aim of giving a picture of the region which is not far from reality but on the other hand which is not that structured. Therefore we can argue that the difference between an anthropologist’s approach to the region and an artist’s approach is based on the difference in their point of focus. This statement one does not deny the importance of the anthropologist’s approach to the region where in fact social

structure appears and thus one can easily understand the way by which society is fonned. To fuiiher the study and understand it in its complexity one cannot deny the importance of literature and culture in the creation of an imaginary.

Castoriadis 71 states that society shares a number of undeniable truths that are

71 Kostantino Kavoulakas Cornelius Castoriadis on social imaginaiy and truth (University of 81

accepted by everyone. By analyzing the imaginary one manages to go beyond

these undeniable truths and thus manages to extend the life of the imaginary itself.

Therefore, if the Mediterranean exists, it is because it managed to create a number of myths and symbols able to renew themselves. The impo1iance of the imaginary for the region itself is based on the fruits that it gives. The Mediterranean that is being mentioned in the various books and poems is supported by the emotions and passions of each and every author. If the author is not moved by passion for the region it would be difficult to create an imaginary. The Mediterranean region is still present in our mind thanks to the imaginary created by the various authors and thinkers.

The choice of the harbour as the locus of a Mediterranean imaginary

comes almost naturally as the harbours facing the Mediterranean Sea have a great impact on culture in the Mediterranean and the threshold between sea and land is on the one hand the very basis of the Mediterranean life. The harbour and the city as two separate and yet same elements intertwine and are able to create rich and variegated cultures, yet they were also the first spectators of conflicts and wars.

From this point of view, it is undeniable that the harbour in the Mediterranean

holds a special place for the author and may be seen by many authors and thinkers as a place of inspiration where ideas concretize and where the emotions, thoughts and ideas brought by the voyage at sea are still very present in the memory.

Crete, September 2000) pp.202-213

82

Through the image of the harbour we come across the image of the sailor

who to many authors has been a point of reflection for the discourse on the

Mediterranean and has helped the connection between the real, almost “filthy” life of the harbor, and the ideas and concepts that fonn in the city. The various authors that integrated the image of the sailor to the idea of the harbour in the

Mediterranean were able to reinforce the Mediterranean imaginary by joining

different images and by giving them life and purpose in a way that goes beyond

the truth. The sailor in Jean-Claude Izzo’ s imaginary has a deep and developed

curiosity and a great knowledge of The Odyssey. While it is not be a surprise that

a sailor has a passion for literature, the point that Jean-Claude Izzo makes is that

Homer’s Mediterranean has definitely changed, yet it is still alive in the heart of

the ones that live the region in all its essence. Therefore, the sailor who is an

everyday image and thus is able to relate to a greater audience acquires almost

different attributes that do not match reality, but that are in essence part of a

shared Mediterranean imaginary.

The way in which authors and thinkers contribute to the fonnation of the

Mediterranean has been the principal focus of this dissertation. The pattern

created by art and literature all over the Mediterranean highlights the differences in the region but it also portrays the similarities that are able to give birth to a unified Mediterranean. As discussed throughout, the process of finding

similarities and the fonnation of an imaginary that is able to constitute the

83

Mediterranean was not a smooth one. The Mediterranean does not in fact appear

as a place that has a lot of common features. Even though politically and

sometimes socially it has been portrayed as a unified region, the unifying factors

are few. Literature does not aim to give a picture of the Mediterranean as one but

aims rather to give various personal and interpersonal interpretations of the region to fonn an imaginary able to be transported and reinterpreted in different

circumstances. It is important to understand that the word ‘imaginary’ does not

aim to conduct a political or social inquiry about the region and that the word in

itself actually aims to understand the underlying concept of the Mediterranean. It does not aim to state facts about the region but rather to give an account that is

able to connect the historical roots of the region to personal experience.

5.2 The Mediterranean ‘Imaginary’ Beyond the Harbour

Although the harbour was my main focus in identifying the Mediterranean

imaginary, it is definitely not the only point in the Mediterranean that could be

taken into account when studying its imaginary. Other aspects of the

Mediterranean could be of great relevance when expanding the various images of the region. One important aspect in all the literature expedients taken into account was the relationship of every author with their nation and their complex identity.

Therefore, in relation to the study conducted, it would be of great interest to expand the notion of ‘nationhood’ and the fonnation of various and complex

84

identities created in the Mediterranean. The Mediterranean nowadays is seen as a region where ‘nationhood’ and identity are created through a complex of knits and relations. The latest ‘citizenship’ programs in all of the northern Mediterranean countries show how the borders and the concept of ‘nationhood’ are deeply changing, most probably opening to further possibilities that range from cultural enrichment to economic advance. When thinking about the Mediterranean JeanClaude Izzo emphasized the fact that he felt that part of himself resided in every harbour and his ‘identity’ was not limited to one place. He makes us realize that the Mediterranean existed before the creation of ‘nations’ and so, each Mediterranean person feels like he can relate to more than one country and more than one culture. The harbour has been the first impact with a deep association to the region, and the person approaching a Mediterranean harbour automatically abandons his roots and is able to relate to what the harbour has to offer. In this sense we have seen how the harbour was vital to the creation of a powerful imaginary. The question of identity and complex relations in the Mediterranean would be a next step in analysing the complexity of the region. The Mediterranean harbour teaches us that all Mediterranean people are prone to the ‘other’ and are open to various cultures, including the exposure to a number of languages and the creation of a lingua .fi’anca to facilitate communication. Therefore, with this exposure promoted by the harbour, the Mediterranean created various identities that sometimes are not distinguishable.

85

Jean-Claude Izzo felt he could relate to almost every country in the

Mediterranean and that part of him resided in every harbour. Nevertheless, he

always saw Marseille as a point of reference and as an anchorage point where his thoughts concretized. Contrarily, the difficult relation of Vincenzo Consolo with the Italian peninsula makes the issue of complex identitites particularly relevant. For a number of years, Consolo worked in northern Italy where he felt like a stranger in his own country. However, with the difference of enviromnent and in a way, a dissimilarity of culture, he was able to contemplate the meaning of the Mediterranean and his native ‘country’, Sicily. The question of a possible or