Tag: Einaudi Editore

Alfabeto Siciliano

Vincenzo Consolo

Quando questo giornale mi propose di scrivere alcune voci di un mio vocabolario, mi si presentarono subito davanti, intimidatori, i fantasmi di Voltaire, di Flaubert, di Savinio e di tanti altri illustri e autorevoli signori. Cercai quindi di imboccare, per cautela, la strada dello scherzo, ma mi trovai nel grigio vicolo del disameno, m’impantanai, per incompetenza, nell’ibrido stagno davanti al bivio del Dizionario dei luoghi comuni e dell’Enciclopedia personale. A mio vantaggio, l’aver fatto solo pochi passi, poche voci della lettera A. Il resto a domani: la vita è lunga e aggiungere noia a noia è poco danno.

AB ANTIQUO La Sicilia è stata Sicilia ab antiquo. Quando Ninive e Persepoli e Gerusalemme, Ebla, Tebe, Menfi, Babilonia, Micene, Sparta, Atene e Roma non esistevano neppure come nomi, quand’erano appena, quelle famose città, piccole, rustiche comunità di cavernicoli e palafitticoli, di pecorai, porcai e contadini, la Sicilia era già Sicilia in tutto lo splendore della sua civiltà. E ogni paese o città di Sicilia è stato civile ab antiquo, più ab antiquo e più civile di qualsiasi altro paese o città di Sicilia.

ACCADEMIA Le accademie sorsero in Francia nel secolo sedicesimo per volere del re allo scopo di promuovere un’arte e una cultura cortigiane, di consenso. Ma in Sicilia le ac-cademie, numerose e fiorenti nei secoli diciassettesimo e diciottesimo, furono sempre oppositive e fucine di un pensiero e di un’arte originali e innovativi che si diffusero in tutto il mondo. Famosissime furono le accademie del Buon Gusto, de’ Geniali, degli Accorti, dei Pericolanti, dei Riaccesi, de’ Gioviali, degli Industriosi, dei Quieti, degli Infiammati, dei Deliranti… Dalle accademie nacquero poi le università, che continuano ancora oggi quella nobile tradizione di diffusione nel mondo, e soprattutto negli Stati Uniti d’America, dell’originale pensiero e cultura siciliani. Modi di dire: « Dentro l’accademia si è tutto, fuori dell’accademia non si è niente», « Chi tocca l’accademia muore », « Diffidare di chi diffida dell’accademia », « Il sentire, il modo d’essere accademico », «In odore d’accademia », eccetera.

AMICIZIA E il più nobile e il più antico sentimento in Sicilia, che si traduce in un profondo ed eterno legame di rispetto e di solidarietà. Un sentimento prevalentemente maschile. Per la sua intensa forza, l’amicizia si espande e si trasferisce in orizzontale, e in progressione geometrica, agli amici degli amici, e in verticale, ai discendenti diretti e ai collaterali, fino a formare consorterie, gruppi, famiglie, cosche, di notevolissima rilevanza sociale. In nome dell’amicizia, si può e si deve fare tutto in Sicilia. Questo sentimento così puro e disinteressato spesso prende forma religiosa e sociale nel comparatico.

AMERICA Fu scoperta dai siciliani in due tempi, all’inizio del 900 e dopo la seconda guerra mondiale. I siciliani d’America si sono sempre divisi in due gruppi: i Doloranti e i Trionfanti. I primi, pavidi e passivi, sono finiti nelle fabbriche e nei lavori più umili e pesanti, lamentandosene, rimpiangendo sempre l’isola d’origine. Dicevano: « La Mérica, la Mérica / fu la sfurtuna mia: / nun era ppi la Mérica, / iu cca nun ci sala ». I secondi, coraggiosi, attivi e intraprendenti, si sono imposti negli Stati Uniti a bagliori di lame d’intelligenza, a colpi di genialità, a raffiche d’azioni precise e produttive, imponendo nel contempo il buon nome della Sicilia. Sono divenuti, i Trionfanti, subito imprenditori e commercianti. Avevano grandi imprese per la gestione del tempo libero, imprese di svaghi e divertimenti con sedi in discreti locali, in sicuri appartamenti e lungo i marciapiedi delle metropoli americane. Commerciavano, negli anni Venti, nel ramo degli alcolici. Dal secondo dopoguerra in poi, si sono specializzati, invece, e ne detengono il monopolio, nell’importazione dai paesi orientali di spezie e coloniali. Questi prodotti, raffinati e opportunamente confezionati in Sicilia, in fabbrichette di fiduciari e corrispondenti dei monopolisti, arrivano in America per essere distribuiti negli States e in tutto il mondo. Il commercio delle spezie è insomma Cosa Loro. Bisogna dire che non è stato molto difficile, per i siciliani Trionfanti, imporsi negli Stati Uniti, perché gli americani non hanno la fantasia, la furbizia e l’intraprendenza dei Mediterranei, sono un po’ infantili, spesso stupidi.

AMORE È il sentimento che domina in assoluto l’ardente cuore dei siciliani. Quanta poesia, quanta letteratura ha creato l’amore in Sicilia! Ha creato anche una scuola ed una lingua: la Scuola poetica siciliana. Se non ci fosse stato Dante, la lingua siciliana si sarebbe imposta in tutta la penisola e oggi in Italia si parlerebbe e si scriverebbe in siciliano. Così, al posto di Fanfani e Spadolini, che sono assurti ai primi posti della scena politica nazionale grazie al loro fluido parlare toscano, noi avremmo avuto presidenti del Consiglio e aspiranti presidenti della Repubblica uomini, che so, come Salvo Lima o l’onorevole Cricchio di Fondachelle. Quante follie, quanti suicidi, quanti omicidi si sono commessi a causa dell’amore! Caterve si contano in Sicilia di ricchi e nobili rovinatisi per amore di bellissime continentali (solo una si rivelò carrapipana), danzatrici e cantatrici, caterve si contano di giuliette e romei, di paoli e francesche, di baronesse di Carini. Dell’amore si dice, antifrasticamente: « Chi è, brodu di luppinu? ».

ANIMA Questa entità spirituale è poco compresa e quindi poco praticata, portati come sono, i siciliani, alla corporalità. Lo si riconosce, questo ánemos, questo vento, solo nelle sue concrete manifestazioni, come Dio si riconosce nelle sue opere: nell’anìmulo, nel vorticare senza posa dell’arcolaio, nella gastrite («bruciuri a’ vucca ‘e l’arma »), nelle strazianti raffigurazioni dei corpi in fiamme delle Anime Purganti… I siciliani, pur ignorando di averne una, sono spesso junghianamente posseduti dall’anima, come i personaggi di Gli anni perduti di Brancati o come il prof. La Ciura della Lighea di Lampedusa. Altri, pur sapendo d’averla, l’anima, avendo letto Platone e San Tommaso, ma giudicandola un vecchio arnese ormai in disuso, la vendono ai rigattieri di anime morte.

ANTENATO Tutti i siciliani hanno gli antenati, più o meno illustri, più o meno titolati. Non ce n’è uno che non coltivi in casa un suo albero genealogico, che non abbia sul portone, su biglietti da visita, stoviglie, posate, camicie, vestaglie, pigiami e mutande, un suo blasone, una sua corona, con più o meno palle. Negli anni Cinquanta e oltre, i comunisti siciliani, forse attanagliati dal rimorso per lo sterminio che i sovietici avevano fatto di questa crema dell’umanità durante la rivoluzione d’ottobre, incettarono i nobili più nobili dell’isola e li iscrissero al partito.

APPARENZA Tutto è apparenza in Sicilia: terra, cielo, mare, flora, fauna, monumenti, scoppi, crepitii, boati, crolli, fumo, urla e sangue. Sono apparenza soprattutto quei cinque o sei milioni di siciliani che in Sicilia vivono e si agitano. Quest’abitudine dei siciliani di chiudere in casa l’essere e mandare in giro l’apparenza, la forma, tutti credono che sia un retaggio della dominazione spagnola. Invece no, il vizio è molto più antico. Risale al tempo in cui il primo straniero sbarcò nell’isola: il Siciliano, terrorizzato nascose dietro la troffa di lentischio la sua realtà (un po’ maleodorante, in quel momento, per la verità) e gli agitò davanti l’ap-parenza. Questo gioco incessante dell’essere e dell’apparire, del nascondere e mostrare, non è che sia piacevole: procura spossatezza, esaurimento, nevrosi e porta qualche volta al delirio. Pirandello ha scritto un’infinità di pagine su questo dramma siciliano. Borges, invece, durante una sua recente visita in Sicilia, guardando (a modo suo) uomini e cose, sembra abbia esclamato, soddisfatto: « Todo fantastico! Todo fan- tasticos! ».

AUTORITÀ Sempre accompagnata da costituita: comando, potere, forza, supremazia, eccetera. I siciliani, estremi come sono in tutti i loro sentimenti, o la odiano o l’adorano, l’Autorità. I primi, per quell’odio, hanno sempre combinato fesserie, che nella storia vengono registrate come rivolte (da quelle degli schiavi, a quella del Vespro, alle rivolte contadine del 1860). I secondi, dalla nascita alla morte, non hanno in testa che quel chiodo fisso: far parte dell’Autorità. Da qui e da sempre, il gran numero, sparso in tutta Italia, di siciliani carabinieri, poliziotti, impiegati delle Imposte e del Catasto, uscieri, cancellieri, giudici, prefetti, capi della Polizia, generali della Finanza. Da qui un gran numero di onorevoli e ministri. Forse questi secondi hanno inventato il famoso detto: «’u cumannari è megghiu du f…», che la Mafia ha subito rovesciato in quest’altro: « Cu cumanna è f… ».

PAOLO DI STEFANO

ANCHE UN DIVERTISSEMENT

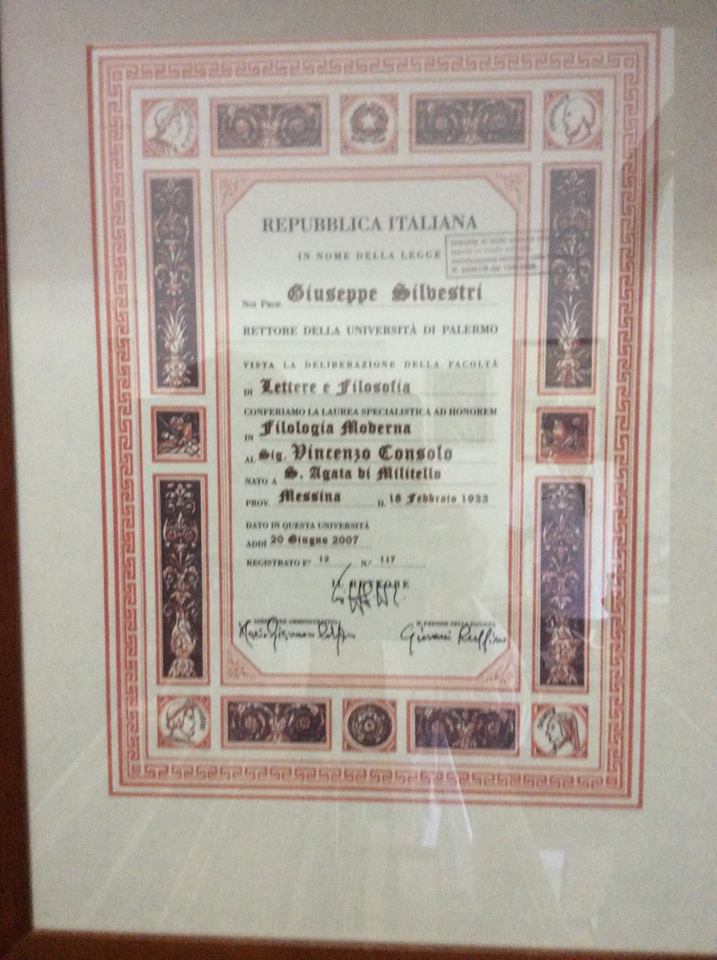

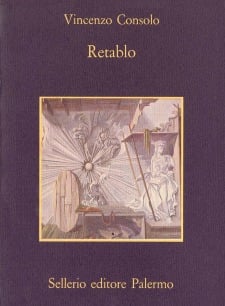

Era la fine del 1985 quando il « Giornale di Sicilia » chiese a Vincenzo Consolo di scrivere un Dizionario personale. Il risultato fu una pagina del 21 dicembre intitolata « Il Vero Siciliano » che esauriva la prima lettera dell’alfabeto con nove voci, da « Ab antiquo» a « Autorità». La brevissima premessa dice l’imbarazzo dello scrittore di fronte a modelli molto ammirati che gli si presentano come fantasmi « intimidatori»: Voltaire, Flaubert e Savinio. Il catenaccio dichiara esplicitamente trattarsi di un dizionario che l’autore « non intende concludere». Un dizionario limitato alla lettera A (« Il resto a domani: la vita è lunga e aggiungere noia a noia è poco danno » è la battuta conclusiva della noticina proemiale) si presenta come un’esperienza programmaticamente concepita nel segno del paradosso e del divertissement. Sin dalla voce iniziale, dove già si annuncia il gioco di parodia degli stereotipi (esterni) e della celebrazione (per lo più autoconsolatoria) cui il Vero Siciliano è facilmente incline. Un gioco per la verità molto serio e forse nato da un impulso rabbioso, che sembra mettere provvisoriamente tra parentesi il rovello doloroso con cui Consolo ha saputo narrare gli orrori della sua Sicilia, anche utilizzando il registro sarcastico (il 1980 è l’anno di Retablo). L’artificio retorico è quello dell’iperbole, che rovescia in positivo i peggiori vizi del carattere siculo (a cominciare dal comparatico nobilmente vissuto come « amicizia »). Per chi ha conosciuto Vincenzo, è difficile leggere queste poche pagine senza ricordare il suo sorriso dolce-amaro, tra beffardo e infantile.

Vincenzo Consolo lettore di Pirandello

CINZIA GALLO

L’attenzione e l’interesse di Consolo per Pirandello sono costanti, come dimostrano i numerosi riferimenti, espliciti od impliciti, allo scrittore agrigentino che Consolo dissemina in gran parte dei suoi lavori. La figura di Pirandello sembra intanto esemplificare la profonda influenza esercitata dai luoghi sugli individui. Infatti, se «si può cadere su questo mondo per caso, […] non si nasce in un luogo impunemente. […] senza essere subito segnati, nella carne, nell’anima da questo stesso luogo» (Consolo 2012: 135)2. In Uomini e paesi dello zolfo, allora, Consolo asserisce: «E, come Pirandello, ogni siciliano credo possa dire “son figlio del Caos”. È il caos prima della formazione del cosmo, la materia informe, la “mescolanza di cose frammiste” di cui parla Empedocle (anch’egli nato nel “caos” d’Agrigento)» (Consolo 1999: 9). Ovviamente Consolo si riferisce alla grandissima varietà della terra siciliana3, dal punto di vista fisico, che gli eventi storici, però, riproducono: Ora qui, per inciso, vogliamo notare che la storia, la storia siciliana, abbia come voluto imitare la natura: un’infinità, un campionario di razze, di civiltà sono passate per l’isola senza mai trovare tra loro amalgama, fusione, composizione, ma lasciando ognuna i suoi segni, qua e là, diversi, distinti dagli altri e in conflitto: 1 Cinzia Gallo, Università di Catania. 2 Consolo ricorda, anche, quanto Pirandello asserisce su se stesso: «Una notte di giugno caddi come una lucciola sotto un gran pino solitario in una campagna d’olivi saraceni…» (Consolo 2012: 135). 3 Sottolinea Consolo: «[…] la Sicilia, […] quest’isola in mezzo al Mediterraneo è quanto fisicamente di più vario possa in sé raccogliere una piccola terra. Un vasto campionario di terreni, argille, lave, tufi, rocce, gessi, minerali… E quindi varietà di colture, boschi, giardini, uliveti, vigne, seminativi, pascoli, sabbie, distese desertiche. In questa terra sembra che la natura abbia subìto come un arresto nella sua evoluzione, si sia come cristallizzata nel passaggio dal caos primordiale all’amalgama, all’uniformazione, alla serena ricomposizione, alla benigna quiete. Sì, crediamo che tutta la Sicilia sia rimasta per sempre quel caos fisico come quella campagna di Girgenti in cui vide la luce Pirandello da qui, forse, tutto il malessere, tutta l’infelicità storica della Sicilia, il modo difficile d’essere uomo di quell’isola, e lo smarrimento del siciliano, e il suo sforzo continuo della ricerca d’identità. Ma questi problemi ci porterebbero lontano, nel magma esistenziale o nel procelloso mare pirandelliano, ed è meglio quindi che rimaniamo ancorati alla terra (Consolo 1999: 10). Dunque, proprio perché Pirandello è «Uomo di zolfo» (Consolo 1999: 26), vissuto a stretto contatto con lo zolfo, ne tratta compiutamente nelle sue opere, che assumono carattere di denunzia. Consolo sottolinea così come nella novella Il fumo appaia chiaramente la «distruzione della campagna da parte della zolfara» (Consolo 1999: 18), mentre in Ciàula scopre la luna «la condizione del caruso […] viene fuori in tutta la sua straziante pena; e […] nei vecchi e i giovani […] il tema dello zolfo serpeggia, prima sommessamente, […] fino ad esplodere nel finale con la rivolta degli zolfatari e con l’eccidio dell’ingegner Aurelio Costa e della sua amante […]» (Consolo 1999: 27). Questi temi, attestanti la funzione civile della letteratura, sempre presente in Consolo, si articolano però in una filosofia «che non è sistema chiuso e definitivo, ma progressione verso […] la poesia» (Consolo 1999: 26). Sembrerebbe, questa, una giustificazione, una spiegazione della narrazione poematica a cui Consolo approda, a partire da L’olivo e l’olivastro, anche se già ne Il sorriso dell’ignoto marinaio se ne notano delle avvisaglie. Pirandello, «un certo Pirandello novelliere e romanziere» rappresenterebbe, inoltre, la letteratura della Sicilia occidentale, «zona fortemente implicata con la storia, […] marcata da temi di ordine relativo – la storia, la cultura, la civiltà, la pace o la guerra sociale», mentre Verga simboleggerebbe la letteratura della Sicilia orientale, «contrassegnata […] da temi di ordine assoluto: la vita, la morte, il mito, il fato […]» (Consolo 2012: 134)4. È stato perciò Pirandello – sottolinea Consolo – a dare ai personaggi siciliani «l’arma della dialettica, del sofisma» (Consolo 1999: 121), in sostituzione della violenza, delle passioni istintive che guidavano i contadini di Verga5. Lo spazio ristretto del villaggio di Trezza, allora, «si restringe ancora di più, si riduce alla stanza borghese, in quella che Giovanni Macchia chiama “la stanza della tortura”, dove si compie ogni violenza, lacerazione, crisi, frantumazione della realtà, perdita di identità. Il movimento, in quella stanza, è solo verbale» (Consolo 1999: 269). 4 Consolo aveva espresso queste idee già nel 1986, in Sirene siciliane, considerando, però, questa «Divisione ideale, immaginaria, […]. E questa idealità è subito contraddetta fatalmente dalla realtà, da spostamenti di autori da una parte verso l’altra: di un poeta come l’abate Meli, per esempio, verso l’Arcadia, verso la mitologia dell’Oriente, o del grande De Roberto verso la storia o lo storicismo d’Occidente» (Consolo 1999: 178-179). 5 Queste idee sono confermate nel 1999, ne Lo spazio in letteratura. Pirandello avrebbe rotto «il cerchio linguistico verghiano», portandolo «su una infinita linearità attraverso il processo verbale, la perorazione, la dialettica, i dissoi lógoi: […] squarcia la scena con la lama dell’umorismo, trasforma l’antica tragedia nel moderno dramma» (Consolo 1999: 269). Non stupisce, dunque, che i due autori, Pirandello e Verga, siano posti uno di fronte all’altro ne L’olivo e l’olivastro. E non è certamente un caso che sia Pirandello, in questo testo, a rendersi conto dell’isolamento, dell’estraneità, nel suo stesso ambiente, retrivo, di Verga, estraneità che un sapiente uso dell’aggettivazione, delle figure retoriche (anafore, metafore, enumerazioni) sottolinea, costituendo, appunto, un esempio di scrittura poematica: Pirandello lo osservò ancora e gli sembrò lontano, irraggiungibile, chiuso in un’epoca remota, irrimediabilmente tramontata. Temette che né il suo, né il saggio di Croce, né il vasto studio del giovane Russo avrebbero mai potuto cancellare l’offesa dell’insulsa critica, del mondo stupido e perduto, a quello scrittore grande, a quell’Eschilo e Leopardi della tragedia antica, del dolore, della condanna umana. Pensò che, al di là dell’esterna ricorrenza, delle formali onoranze, in quel tempo di lacerazioni, di violenza, di menzogna, in quel tramonto, in quella notte della pietà e dell’intelligenza, il paese, il mondo, avrebbe ancora e più ignorato, offeso la verità, la poesia dello scrittore. Pensò che quel presente burrascoso e incerto, sordo alla ritrazione, alla castità della parola, ebbro d’eloquio osceno, poteva essere rappresentato solo col sorriso desolato, con l’umorismo straziante, con la parola che incalza e che tortura, la rottura delle forme, delle strutture, la frantumazione delle coscienze, con l’angoscioso smarrimento, il naufragio, la perdita dell’io. Pensò che la Demente, la sua Antonietta, la suor Agata della Capinera, la povera madre, il fratello suicida di San Secondo, ogni pura fragile creatura che s’allontana, che sparisce, non è che un barlume persistente, segno di un’estrema sanità nella malattia generale, nella follia del presente (Consolo 1994: 67). «Follia del presente» (Consolo 1994: 67) è sicuramente anche quella descritta da Consolo in gran parte dei suoi lavori: pensiamo alla realtà distorta, stravolta, frantumata propria di tutti i testi consoliani, da Il sorriso dell’ignoto marinaio a Lo Spasimo di Palermo. Giustamente, quindi, Consolo è, sostiene Anna Frabetti, un «autore di linea pirandelliana […] in cui il sublime precipita in umoristico, il dramma borghese […] degenera nella “vastasata”, nella farsa del mondo rovesciato, privo di centro» (1995: 1). Una «Vastasata» (Consolo 1985: 10), del resto, è presente in Lunaria, in cui il Vicerè recita «la sua parte di sovrano» (Consolo 1985: 26), definisce «finzione la vita» (Consolo 1985: 66), si mostra consapevole, ricorrendo ad interrogative retoriche ed enumerazioni, della vanità, del carattere relativo del reale: «Dov’è Abacena, Apollonia, Agatirno, Entella, Ibla, Selinunte? Dov’è Ninive, Tebe, Babilonia, Menfi, Persepoli, Palmira? Tutto è maceria, sabbia, polvere, erbe e arbusti ch’hanno coperto i loro resti» (Consolo 1985: 61); e Tutti commentano, con sapiente uso delle figure retoriche: «Così è stato e così [anafora] sempre sarà [poliptoto]: rovinano potenze, tramontano imperi regni civiltà [enumerazione], cadono astri, si sfaldano, si spengono [climax], uguale sorte hanno mitologie credenze religioni. Ogni fine è dolore, smarrimento ogni mutazione [chiasmo], stiamo saldi, pazienza, in altri teatri, su nuove illusioni nascono certezze» (Consolo 1985: 34). E la Sesta donna: «Tutto si frantuma, / cade, passa [climax]» (Consolo 1985: 54). Su questa scia, nella prima sezione di Retablo, Isidoro scorge, nella chiesa di S. Lorenzo, una statua, che reca sul piedistallo la parola«VERITAS» (Consolo 1992: 19), dalle fattezze simili a quelle di Rosalia, ad attestare il carattere apparente, relativo del reale. Lo stesso significato ha, nella terza sezione, l’espressione «Bella, la verità» (Consolo 1992: 149)6 ripetuta da Rosalia che, del resto, sottolinea esplicitamente il contrasto fra apparenza e realtà: «Bagascia, sì, all’apparenza, ma per il bene nostro, tuo e mio»; «Fu per questo che scappai, ch’accettai questa parte dell’amante, questa figura della mantenuta» (Consolo 1992: 149, 155). Se pirandelliana è la costrizione dell’individuo in una forma, Pirandello offre pure le coordinate con cui spiegare l’aspirazione ad essere diversi da quello che si è e con cui si ritiene che ciò sia possibile modificando l’aspetto esteriore, la propria forma, a svuotare di consistenza ruoli e funzioni. Ecco che Consolo, ne Le vele apparivano a Mozia, ricorda come l’«autista-inserviente-guardiano» del pittore Guttuso7, «dal bel nome greco dalla Spagna poi donato alla Sicilia d’Isidoro8 […] come nella novella di Pirandello Sua Maestà, in un desiderio di mimesi, di immedesimazione, si vestiva alla stessa maniera del padrone: giacca e pantaloni blu, camicia azzurra, pullover rosso, fazzoletto rosso che trabocca dal taschino» (Consolo 2012: 124). Anche l’importanza data ai nomi si pone, del resto, sulla scia di Pirandello, che – è noto – istituisce uno stretto «rapporto» fra «nome – identità dei personaggi» (De Villi2013: 278), «per affinità o per antifrasi» (De Villi 2013: 277). Analogamente Consolo esclama: «il destino dei nomi!» (Consolo 2012: 128)9. E la parola, il nome è spesso segno di predestinazione o di destino. Dei nomi dati agli uomini, voglio dire, e dei destini degli uomini: il destino dei nomi. Ma non sappiamo se è l’uomo sul nascere, già segnato da un destino, che si versa e assesta dentro il suo giusto e appropriato involucro di nome (e cognome) oppure se sono il nome e il cognome che, capitati per caso sulla pelle di un uomo come maglietta e brache, ne incidono le carni, ne determinano cioè il destino (Consolo 2012: 66). Definisce, così, le poesie della poetessa Assunta Della Musa, «fra le più ispirate, le più eccitate, le più squisite e belle tra le poesie d’amore scritte in tutti i tempi e in tutti i luoghi. […] Può una donna di nome Assunta Della Musa, coniugata ad Apollo Barilà, non scrivere poesie, essere della poesia, essere la poesia? Essere Erato, la poesia erotica?» (Consolo 2012: 69). Perciò, non a caso, con chiara allusione al leopardiano Dialogo di Plotino e Porfirio, in cui quest’ultimo è 6 Cfr., su questo argomento, Galvagno 2015: 39-64. 7 È, questi, l’unico pittore a cui Consolo attribuisce, ne L’enorme realtà, «il dono della capacità del racconto, della rappresentazione […] che hanno avuto scrittori come Verga, come Pirandello, come Sciascia» (Consolo 1999: 271). 8 Con caratteristiche simili, a confermare l’importanza dei nomi, in Lunaria si chiama Isidoro il maestro di cerimonie del Vicerè, attento alle apparenze, «intransigente custode di […] inderogabili forme palatine» (16). 9 In Lunaria, gli abitanti della «selvaggia Contrada senza nome» sono «uomini senza legge, senza lingua, senza storia, anime boschive, […]» (61).

consapevole della «vanità di ogni cosa» (Leopardi 1978: 530), si chiama Porfirio il valletto di Casimiro, il vicerè di Lunaria, che non prende mai la parola, ma è consapevole della «recitazione» (Consolo 1985: 10) del suo signore. Lucia, poi, si chiama – per antifrasi in rapporto all’etimologia del nome –, la sorella di Petro Marano, affetta da disturbi mentali. E il quinto capitolo di Nottetempo, casa per casa, che la mostra, alla fine, pazza, reca, in epigrafe, una battuta di Come tu mi vuoi: «Chiami, chi sa da qual momento lontano… felice…/ della tua vita, a cui sei rimasta sospesa… là…» (Consolo 1992: 59). Erasmo, ancora, con probabile riferimento ad Erasmo da Rotterdam e al suo Elogio della follia – oltre che, a confermare la rilevanza attribuita dal nostro scrittore allo spazio – al piano di sant’Erasmo, nei dintorni di Palermo, si chiama il «vecchietto lindo, bizzarro» (Consolo 1998: 103) de Lo Spasimo di Palermo, a cui è affidato il compito di mettere in evidenza, alla fine del romanzo, l’importanza della letteratura. Costui, infatti, coinvolto nell’attentato al giudice Borsellino, recita, in punto di morte, due versi de La storia di la Baronissa di Carini, ad attestare come, anche se al presente la letteratura non è ascoltata, è da questa, voce della tradizione, della memoria storica, che deve venire la salvezza: O gran mano di Diu, ca tantu pisi, cala, manu di Diu, fatti palisi! (Consolo 1998: 131) E, ancora, Consolo dichiara: «La salvezza è stata solo nel linguaggio. Nella capacità di liberare il mondo dal suo caos, di rinominarlo, ricrearlo in un ordine di necessità e di ragione» (Consolo 1999: 272). Petro Marano, perciò, si aggrappa «alla parole, ai nomi di cose vere, visibili, concrete», desideroso di «rinominare, ricreare il mondo» (Consolo 1992: 42-43). Egli, poi, alla fine si rifugia a Tunisi, così come anche Lando Laurentano avrebbe voluto imbarcarsi per Malta o per Tunisi (Pirandello 1953: 394). Consolo, quindi, mette in relazione, attraverso la figura di Antonio Crisafi de La pallottola in testa, il disagio, l’estraneità dell’intellettuale nella moderna società, sia quella del «Meridione depresso» (Consolo 2012: 157) sia quella legata all’avvento dei mass media, della televisione, all’isolamento del professor Lamis de L’eresia catara di Pirandello. Ed anche in Un giorno come gli altri, discutendo della funzione dell’intellettuale, Consolo si richiama a Pirandello. A proposito, infatti, della differenza, instaurata da Moravia e Vittorini, fra artista e intellettuale, egli asserisce: A me la distinzione sembra vecchia, mi ricorda l’affermazione di Pirandello: “La vita, o la si scrive o la si vive”. Ché l’alternativa, oltre a valere per tutti, non solo per l’artista, dopo Marx non ha più senso. Oggi siamo tutti intellettuali, siamo tutti politici, […]. Il problema mi sembra che stia nel voler essere o no dentro le “regole”, nel voler essere o no, totalmente, incondizionatamente, dentro un partito, dentro la logica “politica” di un partito. Questo mi sembra il punto, il punto di Vittorini (Consolo 2012: 91-92). Arriva, quindi, alla sua celebre distinzione fra scrivere e narrare: Riprendo a lavorare a un articolo per un rotocalco sul poeta Lucio Piccolo. Mi accorgo che l’articolo mi è diventato racconto, che più che parlare di Piccolo […] in termini razionali, critici, parlo di me, della mia adolescenza in Sicilia, di mio nonno, del mio paese: mi sono lasciato prendere la mano dall’onda piacevole del ricordo, della memoria. […] È […] il narrare, operazione che attinge quasi sempre alla memoria, […]. Diverso è lo scrivere, […] operazione […] impoetica, estranea alla memoria, che è madre della poesia, come si dice. E allora è questo il dilemma, se bisogna scrivere o narrare. Con lo scrivere si può forse cambiare il mondo, con il narrare non si può, perché il narrare è rappresentare il mondo, cioè ricrearne un altro sulla carta (Consolo 2012: 92)10. Pirandello simboleggia la Sicilia, insieme a Verga, Meli, Capuana, secondo il mafioso catanese, sottoposto al 41 bis nel carcere di Opera – Milano, dopo aver «fatto un bel po’ di strada negli affari, appalti, commerci vari» (Consolo 2012: 216): Consolo ironizza sulla politica separatista, portata avanti dal Movimento indipendentista siciliano di Finocchiaro Aprile e, di conseguenza, sulla politica della Lega Nord, sottolineando ancora una volta l’importanza della memoria storica. Si pone, ancora, accanto a Pirandello, dichiarando che Il sorriso dell’ignoto marinaio «era d’impianto storico» ma «voleva anche dire metaforicamente del momento che allora si viveva, a Milano e altrove» (Consolo 2012: 119): «(si svolgeva negli anni del Risorgimento e dell’impresa garibaldina: nodo di passaggio storico importante per il Meridione e banco di prova della maggior parte degli scrittori siciliani – Verga, De Roberto, Pirandello, Lampedusa, Sciascia…)» (Consolo 2012: 119)11, accomunati tutti, «da Verga a De Roberto, a Pirandello», da «un costante immobilismo» (Consolo 1999: 169)12, pur nella diversità delle posizioni ideologiche. In particolare, se la rinuncia a rappresentare la rivolta parrebbe accomunare Il sorriso dell’ignoto marinaio a I vecchi e i giovani, le motivazioni dei due scrittori sono differenti. Consolo, consapevole «dei limiti di classe degli intellettuali», nutre «sfiducia nella possibilità, da parte della letteratura, di rendere la visione e il sentire delle classi subalterne senza stravolgimenti mistificatori»; Pirandello, invece, è mosso da un profondo «pessimismo» che lo induce «a svalutare anche gli eventi più tragici ed epocali come frutto di vane illusioni e follie destinate ad essere cancellate dal 10 Nel 1997, richiamandosi alle tesi espresse da Walter Benjamin in Angelus novus, Consolo preciserà: «E c’è, nella narrazione, un’idea pratica di giustezza e di giustizia, un’esigenza di moralità». (Consolo 1999: 144). Per quest’argomento, cfr. Francese 2015. L’influsso di Benjamin su Consolo è stato evidenziato anche da Daragh O’Connell (2008: 161-184), che ricorda la traduzione in italiano de Il narratore di Benjamin effettuata, per Einaudi, da Renato Solmi nel 1962 (162, nota 2). 11 Pure ne Il sorriso, vent’anni dopo, Consolo asserisce che il suo romanzo è nato da una «rilettura della letteratura che investe il Risorgimento, soprattutto siciliana, ch’era sempre critica, antirisorgimentale, che partiva da Verga e, per De Roberto e Pirandello, arrivava allo Sciascia de Il Quarantotto, fino al Lampedusa de Il Gattopardo» (Consolo 1999: 279). 12 Consolo ricorda come i critici di orientamento lukácsiano avessero posto Il Gattopardo accanto a I Vicerè di De Roberto e a I vecchi e i giovani di Pirandello (Consolo 1999: 173). tempo, […]» (Baldi 2014: 254). In entrambi i romanzi, però, il Risorgimento si risolve in una «disillusione del vecchio sogno della terra» (Consolo 2012: 109)13 e nei pensieri di Lando Laurentano si scorge un’eco di quei contrasti di classe che Consolo pone in primo piano14: «Da una parte il costume feudale, l’uso di trattar come bestie i contadini, e l’avarizia e l’usura; dall’altra l’odio inveterato e feroce contro i signori e la sconfidenza assoluta nella giustizia, si paravano come ostacoli insormontabili a ogni tentativo per quella cooperazione» (Pirandello 1953: 392)15. E precedentemente, ascoltando il discorso di Cataldo Sclàfani, considera: «Una buona legge agraria, una lieve riforma dei patti colonici, un lieve miglioramento dei magri salarii, la mezzadria a oneste condizioni, come quelle della Toscana e della Lombardia, come quelle accordate da lui nei suoi possedimenti, sarebbero bastati a soddisfare e a quietare quei miseri […]» (Pirandello 1953: 288). Ne Il sorriso dell’ignoto marinaio, del resto, anche la figura di Garibaldi, su cui si concentrano le aspettative dei ‘giovani’ (Roberto Auriti, Mauro Mortara, Corrado Selmi, Rosario Trigona), consente di stabilire delle corrispondenze con Pirandello. Consolo, difatti, sottolinea il favore ottenuto da Garibaldi («[…] vanno dicendo che [Garibaldi] gli dà giustizia e terre.»), ritenuto però, al tempo stesso, un «Brigante. Nemico di Dio e di Sua Maestà il Re […] Scanna monache e brucia conventi, rapina chiese, preda i galantuomini e protegge avanzi di galera…» (Consolo 2004: 66). E ribadisce le sue riserve su Garibaldi anche in altri testi. Parlando, nel 1982, della rivolta di Bronte, dell’agosto 1860, Consolo, oltre ad evidenziare la «crudeltà», la «sommarietà di giustizia» (Consolo 2012: 108) di Bixio, afferma riguardo Garibaldi: In questa annata di celebrazione garibaldinesca in chiave post-moderna, in cui tutti gli stili, le citazioni, i repêchages si fanno stile, in cui le pagine chiare e oscure, le glorie e le vergogne, le vittime e gli scheletri, più che nascosti nell’armadio, esibiti si fanno levigato stile eroico, gloriosa epopea da consumo, soffermarsi 13 Scrive Pirandello: «Sì, aveva esposto la verità dei fatti quel deputato siciliano: quei contadini di Sicilia, […] s’erano recati a zappare le terre demaniali usurpate dai maggiorenti del paese, amministratori ladri dei beni patrimoniali del Comune: intimoriti dall’intervento dei soldati, avevano sospeso il lavoro ed erano accorsi a reclamare al Municipio la divisione di quelle terre; […]» (Pirandello 1953: 238). 14 Pensiamo a quest’episodio, che trova corrispondenza nella terza scritta al nono capitolo: «“Ah ah, puzzo di merda, papà, ah ah” sentirono ancora alle spalle che faceva Salvatorino, grasso come ‘na femmina, babbalèo, mammolino, ancora a quindici anni sempre col dito in bocca, la bava e il moccio, unico erede, presciutto tesoro calasìa, al padre professore Ignazio e al nonno sindaco, il notaio Bàrtolo. / Tanticchia girò la testa sopra il tronco e lo guatò sbieco. / “Garrusello e figlio di garruso alletterato!” disse, e poi sputò per terra, bianco e sodo, tondo come un’onza» (Consolo 2004: 95-96). 15 Lo stesso Consolo ricorda le «Insurrezioni che spesso non sono solo contro i borbonici, ma di contadini e braccianti contro i loro nemici di sempre, i nobili e i borghesi che quasi dappertutto avevano usurpato terre demaniali» (Consolo 2012: 107). 178 su un episodio come quello di Bronte, estrapolarlo dal contesto post-moderno, appunto, può farci apparire fuori moda, arretrati, forse striduli (Consolo 2012: 107) Ma che Consolo consideri in modo non del tutto positivo Garibaldi e il suo influsso è dimostrato, ancora, dai giudizi formulati nell’articolo Il più bel monumento: Questo ironico (speriamo) e autoironico personaggio, nella sua campagna d’Italia, non fece che imitare, nel dire, nel fare e nel posare, il monumento di sé ch’era già idealmente eretto, in uno spassoso scambio tra l’immagine e il reale, in gara di esaltazione e in doppio accrescimento senza fine. Tutti rimasero vittime del giuoco, e ogni città e villa non poté che innalzargli il monumento. […] Ed era questo che Garibaldi in fondo desiderava: volare, volare in un teatrino d’invenzione per dimenticare le colpe e sopire i rimorsi che dentro gli rodevano (Consolo 2012: 70-71). Analogamente, nella novella pirandelliana L’altro figlio, Garibaldi è colui che «fece ribellare a ogni legge degli uomini e di Dio campagne e città» (Pirandello 1955: 242). E Maragrazia prosegue, servendosi di enumerazioni, metafore, esclamazioni, paragoni, puntini di sospensione, per coinvolgere emotivamente il lettore e rendere il suo racconto più persuasivo: […] vossignoria deve sapere che questo Canebardo diede ordine, quando venne, che fossero aperte tutte le carceri di tutti i paesi. Ora, si figuri vossignoria che ira di Dio si scatenò allora per le nostre campagne! I peggiori ladri, i peggiori assassini, bestie selvagge, sanguinarie, arrabbiate da tanti anni di catena… Tra gli altri, ce n’era uno, il più feroce, un certo Cola Camizzi, capo-brigante, che ammazzava le povere creature di Dio, così, per piacere, come se fossero mosche, per provare la polvere, – diceva – per vedere se la carabina era parata bene. […] Ah, che vidi! […] Giocavano… là, in quel cortile… alle bocce… ma con teste d’uomini… nere, piene di terra… le tenevano acciuffate pei capelli… e una, quella di mio marito… la teneva lui, Cola Camizzi… e me la mostrò. […] cane assassino! (Pirandello 1955: 242-244). Pirandello è per Consolo, ancora, il termine di paragone attraverso cui giudicare i testi della contemporaneità, a metterne in evidenza la vitalità, il carattere paradigmatico. Asserisce così: «La storia di Creatura di sabbia [di Tahar Ben Jelloun] è una delle più felici invenzioni letterarie del romanzo contemporaneo, uguale forse, per la metafora, per la verità profonda che riesce a liberare, a quella de Il fu Mattia Pascal di Pirandello» (Consolo 1999: 232-233). Analogamente, pure vari aspetti della produzione di Sciascia sono spiegati in rapporto a Pirandello. Nella prefazione a Le epigrafi di Leonardo Sciascia di Pino Di Silvestro, Consolo considera quale «più grande epigrafe di tutta l’opera di Sciascia, non scritta ma vistosamente implicita, […] la stanza della tortura pirandelliana declinata sul piano della storia, sul palcoscenico della violenza, della sconfitta» (Consolo 1999: 202). Tre anni più tardi, nel 1999, Consolo, evidenziando la funzione civile sottesa all’opera di Sciascia, gli attribuisce il merito di avere spostato «la dialettica pirandelliana dalla stanza alla piazza, nella civile agorà» (Consolo 1999: 269). Sciascia, allora, in questa sua «conversazione loica e laica sui fatti sociali e politici» si rivela «figlio di Pirandello» (Consolo 1999: 186), al punto tale che il personaggio narrante di Todo modo è «nato e per anni vissuto in luoghi pirandelliani, tra personaggi pirandelliani – al punto [dice] che tra le pagine dello scrittore e la vita che avevo vissuto fin oltre la giovinezza, non c’era più scarto, e nella memoria e nei sentimenti» (Consolo 1999: 187-188). Quest’interesse, questa consonanza di idee con Pirandello, porta Consolo a riunire in Di qua dal faro, con il titolo di Asterischi su Pirandello, alcuni saggi dedicati allo scrittore agrigentino, pubblicati fra il 1986 e il 1997. In Album Pirandello Consolo ribadisce la funzione modellizzante che lo spazio ha esercitato su tutta la famiglia dello scrittore agrigentino: «quell’albero genealogico […] dispiega i suoi rami contro un cielo di luce crudele, affonda le sue radici in quell’asperrimo terreno che è la Sicilia, in quel caos di marne e di zolfi che è Girgenti» (Consolo 1999: 150). E così anche l’eclissi di sole a cui assistette «graverà sul mondo dello scrittore» (Consolo 1999: 150) e si combinerà con «quella […] della città in cui si trovò a vivere, di Girgenti. Una città dove è morta la storia, la civiltà, lasciando il vuoto, il deserto, […] la stasi, l’immobilità» (Consolo 1999: 150-151). Ricordiamo, difatti, che Consolo, ne L’olivo e l’olivastro e ne Lo Spasimo di Palermo, per esempio, individua, nella perdita della memoria storica, la causa della crisi del presente. Scrive così: «si può mai narrare senza la memoria?»; «Non è vero, io non so scrivere di Milano, non ho memoria» (Consolo 2012: 88, 97). Unica soluzione, allora, l’evasione, come quelle di Mattia Pascal o di Enrico IV, oppure rivestire delle forme, difenderle con le armi della dialettica, del sofisma, della retorica. L’operazione di Pirandello sembra perciò trovare dei riscontri nell’età contemporanea, in cui «l’io s’è perso nell’indistinta massa, la vita nelle prigioni sempre più disumane delle forme imposte dal potere, l’essere nell’apparire fantasmatico dei media» (Consolo 1999: 152). E non dimentichiamo che pure Consolo considera negativamente l’omologazione. Gioacchino Martinez, per esempio, sul treno che lo conduce a Palermo, prova piacere «a risentire quei suoni, quelle cadenze meridionali, quelle parlate che non erano più dialetto, ma non ancora la trucida nuova lingua nazionale» (Consolo 1998: 94-95) annunciata da Pasolini. Il viaggiatore de L’olivo e l’olivastro, poi, giudica «vacui» i giovani che, «con l’orecchino al lobo, i lunghi capelli legati sulla nuca» (Consolo 1994: 112), affollano la piazza di Avola. Altri legami fra Pirandello e Consolo ne L’ulivo e la giara. Gli stucchi di Giacomo Serpotta, che lo scrittore agrigentino ebbe modo, molto probabilmente, di osservare nella chiesa di Santo Spirito, con il loro carattere «mortuario […] fantasmatico» che «ha colto il pittore Fabrizio Clerici nella sua Confessione palermitana» (Consolo 1999: 156), hanno influenzato pure Consolo, il quale, in Retablo, chiama Fabrizio Clerici il protagonista e descrive le sculture in stucco dell’oratorio di via Immacolatella di Procopio Serpotta, figlio di Giacomo. «La bianca, spettrale fantasmagoria serpottiana» (Consolo 1999: 156), inoltre, richiama la «servetta Fantasia» attraverso cui i vari personaggi delle opere letterarie si materializzano, così come Macchia per Pirandello e Carandente per Serpotta parlano del «cannocchiale rovesciato» (Consolo 1999: 157). Analogamente, la superiorità di Cefalù su Palermo, sostenuta da Consolo varie volte16, è colta anche da Pirandello. Consolo immagina che questi, in viaggio da Palermo a Sant’Agata, in preda alla profonda suggestione «che gli suscitavano i nomi dei paesi: Solunto, Himera, Cefalù, Halaesa, Calacte…», si accorge che, «dopo Cefalù, il mondo colorato, vociante e brulicante del Palermitano andava a poco a poco stemperandosi [per] a prendere gradualmente una misura più dimessa, ma forse più serena» (Consolo 1999: 157-158). Pirandello, a confermare l’importanza dei luoghi, ebbe sicuramente presente, secondo Consolo, «il ricordo di quel suo lontano viaggio nel Val Dèmone» (Consolo 1999: 161) nello scrivere La giara, «la prima fuga nella memoria e nel ricordo, fuga dalla sua vita e dai fantasmi “pirandelliani” che lo assediavano» (Consolo 1999: 160). La novella, perciò, giudicata di recente una «divertita denuncia dell’intrinseca capziosità sia delle vicende che delle soluzioni giuridiche, calata in pieghe di umoristica densità» (Zappulla Muscarà 2007: 143), acquista nuovo significato nell’interpretazione di Consolo. La giara è per lui, infatti, a richiamare la sua tipica figura chiave della chiocciola, della spirale, sia «l’involucro della nascita, l’utero» sia «la tomba», mentre «quell’olio che la giara avrebbe dovuto contenere viene sì dall’ulivo saraceno, ma viene anche dall’albero sacro ad Atena, dea della sapienza» (Consolo 1999: 161-162), a ricordare la commistione delle due culture, araba e greca, della Sicilia. Consolo può allora vedere nel pino di Pirandello, tranciato, un simbolo degli «scadimenti, delle perdite, reali e simboliche, nel nostro Paese» (Consolo 1999: 163), a confermare la «visione del mondo, della vita come caos, mutamento incessante di forme, […] approdo all’assenza, al nulla» (Consolo 1999: 165). Anche in ciò Consolo si trova in consonanza con Sciascia17, che commenta, alla fine di Fuoco dell’anima: «Questa è la classe dirigente – per meglio dire digerente – che preferisce fare il pino di plastica piuttosto che salvare quello vero. Ed è così per tante, tante altre cose…» (Consolo 1999: 164). Con tutto questo, Consolo mostra l’importanza della ricezione dei testi letterari, avvicinandosi al lector in fabula descritto da Eco (1979). 16 Mi sia consentito, per questo, un rimando a Gallo 2017: 287-296. 17 Gianni Turchetta sottolinea, a proposito del termine ‘impostura’ de Il sorriso dell’ignoto marinaio, i legami di Consolo con Sciascia (2015: 1304-1305). Ne Lo Spasimo di Palermo, inoltre, Gioacchino Martinez legge, ne La corda pazza, la vita di Antonio Veneziano (115) e il narratore ricorda il «rifugio in Solferino dove Sciascia patì la malattia, sua del corpo e insieme quella mortale del Paese» (93-94). Vincenzo Consolo lettore di Pirandello 181

Bibliografia

Baldi G., 2014, Microscopie, Napoli, Liguori. Consolo V., 1985, Lunaria, Torino, Einaudi. Consolo V., 1992, Nottetempo, casa per casa, Milano, Mondadori. Consolo V., 1992, Retablo, Milano, Mondadori. Consolo V., 1994, L’olivo e l’olivastro, Milano, Mondadori. Consolo V., 1998, Lo Spasimo di Palermo, Milano, Mondadori. Consolo V., 1999, Di qua dal faro, Milano, Mondadori. Consolo V., 2004, Il sorriso dell’ignoto marinaio, Milano, Mondadori. Consolo V., 2012, La mia isola è Las Vegas, Milano, Mondadori. Consolo V., 2015, L’opera completa, a cura e con un saggio introduttivo di Gianni Turchetta e uno scritto di Cesare Serge, Milano, Mondadori, «I Meridiani». De Villi A. I., 2013, «Pasquale Marzano, Quando il nome è “cosa seria”. L’onomastica nelle novelle di Luigi Pirandello», (Pisa, ETS, 2008, 206 p.), OBLIO III, 9-10, p. 277-279. Eco U., 1979, Lector in fabula, Milano, Bompiani. Frabetti A., 1995, «L’“infinita derivanza”. Intertestualità e parodia in Vincenzo Consolo», Bollettino ‘900, n. zero, maggio, n. 1, http://www.comune.bologna. it/iperbole/boll900/consolo.htm Francese J., 2015, Vincenzo Consolo, Firenze, University Press. Gallo C., 2017, La Yoknapatawpha di Vincenzo Consolo, in: Sgavicchia S., Tortora M., Geografie della modernità letteraria, Pisa, ETS, I, p. 287-296. Galvagno R., 2015, «“Bella, la verità”. Figure della verità in alcuni testi di Vincenzo Consolo,» in: Diverso è lo scrivere. Scrittura poetica dell’impegno in Vincenzo Consolo, Avellino, Edizioni Sinestesie, p. 39-64. Leopardi G., 1978, I Canti. Operette morali, Roma, Casa Editrice Bietti. O’Connell D., 2008, «Consolo narratore e scrittore palincestuoso», Quaderns d’Italià, 13, p. 161-184. Pirandello L., 1953, I vecchi e i giovani, in: Tutti i romanzi, vol. II, Milano, Mondadori. Pirandello L., 1955, Novelle per un anno, Milano, Mondadori, vol. II. Turchetta G., 2015, «Note e notizie sui testi», in: Consolo V., L’opera completa, p. 1271-1455. Zappulla Muscarà S., 2007, «La Giara e La patente fra narrativa e teatro ovvero Pirandello nell’isola del sofisma», in: Lauretta E., Novella di Pirandello: dramma, film, musica, fumetto, Pesaro, Metauro, p. 143-167.700

Retablo e altra narrativa di Vincenzo Consolo: lingua e significato nei nomi paralleli di scritture parallele

Enzo Caffarelli

Di Vincenzo Consolo sono stati più volte e da più voci messi in luce i percorsi paralleli della scrittura. Solo per citarne alcuni: – il racconto che si affianca all’immagine, all’illustrazione; l’opera consoliana è costantemente caratterizzata da riferimenti alle arti figurative. Se, in Retablo, al centro della vicenda è posto il dipinto, a scomparti e a scene, che intitola l’opera, nel Sorriso dell’ignoto marinaio un ritratto di Antonello da Messina fa da filo conduttore del romanzo; Raffaello figura con il suo Spasimo di Sicilia (Andata al Calvario) appunto nello Spasimo di Palermo; nell’Olivo e l’olivastro, Caravaggio approda a Siracusa per dipingere il Seppellimento di Santa Lucia. Un saggio di Consolo reca il titolo di un quadro di Renato Guttuso, Fuga dall’Etna;1 ancora in Retablo, si pensi all’inventario del museo del Soldano Lodovico, alla descrizione dei resti di Selinunte e alla menzione di pittori contemporanei. Peraltro le citazioni pittoriche sono spiegate dallo stesso Consolo,

memore delle riflessioni di Cesare Segre,2 con 1 Fuga dall’Etna. La Sicilia e Milano, la memoria e la storia, Roma, Donzelli 1993. «Il riferimento all’opera guttusiana testimonia di un’amicizia e di una consonanza ideale che si traduce in altre citazioni presenti nei romanzi, fino a giungere ad una più ampia riflessione critica nel saggio L’immensa realtà, compreso nella silloge Di qua dal faro» (Dario Stazzone, «Quel pittore celebrato della Bagarìa». Guttuso nell’opera di Vincenzo Consolo, «Oblio», IV (2014), 14-15, pp. 79-90, p. 81). 2 Cfr. Cesare Segre, La pelle di San Bartolomeo, Torino, Einaudi 2003, dedicato al nesso tra lettura e pittura e ai rapporti di transcodificazione, studio conosciuto e meditato da Consolo, come la ricerca di un equilibrio tra temporalità e spazialità, come affermato in un’intervista concessa a Giuseppe Traina:

Credo ci sia bisogno di equilibrio tra suono e immagine, come una sorta di compenso, perché il suono vive nel tempo, invece la visualità vive nello spazio. Cerco di riequilibrare il tempo con lo spazio, il suono con l’immagine. Poi sono stati motivi d’ispirazione, di guida, le citazioni iconografiche di Antonello da Messina o di Raffaello. In Retablo c’è l’esplicitazione dell’esigenza della citazione iconografica: il ‘retablo’ appartiene alla pittura ma è anche ‘teatro’, come nell’intermezzo di Cervantes;3 – la poesia che, anziché rappresentare uno sviluppo autonomo e nettamente distinto dalla prosa nella produzione dello scrittore – come in altri Siciliani contemporanei (Sciascia, Bufalino, D’Arrigo, Bonaviri, ecc.) – s’infiltra nella prosa stessa, scandendo un ritmo particolarissimo per opere come Retablo e, prima, La ferita dell’aprile (ma anche Nottetempo casa per casa e altro). Si tratta di un ritmo intessuto su frequentissimi endecasillabi (e inoltre settenari e dodecasillabi): ne ho contati 62 soltanto nelle 7 pagine dell’introduttivo «Oratorio», spesso a coppie, talvolta più numerosi, fino a 5 consecutivi.4 In un passo della «Peregrinazione» sono 6 i consecutivi;5 nelle 6 righe tipografiche iniziali del cap. ‘In Egesta degli Elìmi’ risultano 8, e 6 nella descrizione della statua della Veritas (p. 23), nella quale Isidoro

riconosce la sua Rosalia (e che si conclude con un verso di sapore dantesco: «urlai, e caddi a terra tramortito»); sono 9 nella presentazione del retablo delle meraviglie da parte dello «scoltor d’effimeri Crisèmalo» e del «poeta vernacolo Chinigò». Ne sono ricchi soprattutto gli incipit (cfr. anche Lunaria e Nottetempo casa per casa). Ma, insieme alla lirica ‘alta’, Consolo mira alla rievocazione di echi strofici popolari; egli stesso ribadiva il suo amore per le narrazioni ritmiche, i cantastorie, i racconti orali che, a forza di ripetersi, perdono tutto ciò che non è essenziale; – la miscela di storia reale e di finzione, anche nei nomi propri. In Retablo non solo il protagonista e io narrante della centrale Peregrinazione, Fabrizio Clerici, corrisponde a un personaggio reale (1913-1993), ma il pittore Clerici e l’amico Consolo compirono effettivamente un viaggio in Sicilia e visi-

dimostra la sua comunicazione Antonello e altri pittori, letta presso l’Accademia Carrara di Bergamo il 4 febbraio 2004 (cito da Stazzone, «Quel pittore…, cit., p. 79). 3 Cfr. Giuseppe Traina, Vincenzo Consolo, Fiesole (Firenze), Ed. Cadmo 2001, p. 130. 4 «Dio che/ non mi scansò dalle nasse o rizzelle/ che un bel dì si misero a calarmi/ una coppia di donne, madre e figlia/ ch’io d’un subito, fraticello mondo,/ credei di casa, oneste e timorate» (p. 18). Per la numerazione delle pagine seguo la 1ª ediz. «Il castello», Palermo, Sellerio 1990. 5 «È una terra nordica, luntana,/ ’na piana chiusa da montagne altissime/ d’eterni ghiacci e d’intricati boschi,/ rotta da lunghi fiumi e laghi vasti,/ terra priva di mare, cielo, sole,/ stelle, lune, coi verni interminabili», 49

-tarono alcuni luoghi poi rappresentati nel racconto, per es. Mozia sull’isola di San Pantaleo.6 Clerici era un grande estimatore di Giacomo Serpotta, più volte citato in Retablo come lo scultore (e decoratore) palermitano che usa come modella la Rosalia di Isidoro. Si pensi poi ai soprannomi dei pittori, elencati da Isidoro, quando si complimenta con don Fabrizio per un suo disegno appena abbozzato: «Siete meglio del Monrealese, meglio dello Zoppo 1di Gangi, del Monocolo di Racalmuto, meglio di quel pittore celebrato (non ricordo il nome) della Bagarìa»7 (pp. 62-63). E al barone Enrico Pirajno di Mandralisca, nel Sorriso dell’ignoto marinaio, al marinaio Giovanni Interdonato, al capopopolo Filippo Siciliano e altri personaggi di Ratumemi (dalle Pietre di Pantalica), ecc.; – l’amore religioso e l’amore carnale, come emergono da Retablo e in particolare dalla santa e dalle donne che portano il nome Rosalia… ma anche nella vita e figura della santa, «doppia nella grotta che si vuole sia stata il suo eremo, tra Monte Pellegrino e la Quisquina, doppia anche nel regno delle immagini, se è vero che alla fanciulla siciliana van Dyck impresse i lineamenti di una florida giovinotta fiamminga, bionda e dall’incarnato roseo, che si sarebbe presto imposta sull’altra figura, emaciata come si conviene a una eremita».8 In fondo, la Rosalia che ha indotto in tentazione il fraticello Isidoro è, paradossalmente, anche l’immagine della santa – nella statua del Serpotta – cui il poveretto si rivolge nelle sue preghiere; – la scelta di un linguaggio che combina elementi non solo lontani dall’italiano standard o dagli standard regionali, ma si muove sul piano lessicale, fonetico, morfologico e sintattico su piani paralleli, con il recupero colto di latinismi e grecismi, di arabismi e con il ricorso al dialetto nelle sue sfumature, una lingua ‘verticale’, in contrasto con quella orizzontale, «rigida e anche fragile perché invasa da un super-potere economico che non è il nostro».9 Ha scritto Cesare Segre, a proposito del Sorriso dell’ignoto marinaio, del tentativo di «far esplodere il linguaggio medio, spingendolo contemporaneamente verso i livelli più alti e quelli più bassi dello spazio linguistico»;10

6 Cfr. Paolo Mauri, Fabrizio delle meraviglie, «la Repubblica.it», 8/10/1987; in rete: http://ricerca. repubblica.it/repubblica/archivio/repubblica/1987/10/08/fabrizio-delle-meraviglie.html. 7 I pittori sono facilmente identificabili: il Monrealese è Pietro Novelli, secentista caro anche a Federico De Roberto, che lo cita nei suoi romanzi; lo Zoppo di Gangi è pseudonimo dietro cui si celano due pittori manieristi; il Monocolo di racalmuto o Monocolus Recalmutensis è Pietro D’Asero; il non nominato è tale perché si tratta di un contemporaneo del Clerici reale e di Consolo, Renato Guttuso. 8 Sergio Troisi, Van Dyck a Palermo e la Santuzza girò il mondo, «la Repubblica.it», 9/07/2015. 9 C fr. le interviste di Italialibri: Intervista con Vincenzo Consolo, gennaio-febbraio-marzo 2001, in rete: www.italialibri.net/interviste/consolo/consolo31.html. 10 Cesare Segre, La costruzione a chiocciola nel Sorriso dell’ignoto marinaio di Vincenzo Consolo, in Intreccio di voci, Torino, Einaudi 1991, pp. 71-86.

– la scelta di nomi che hanno spesso una doppia motivazione, come nel caso della famiglia di Pietro Marano in Nottetempo casa per casa: Ho adottato questo nome perché ha due significati per me. Marano significa marrano, cioè l’ebreo costretto a rinnegare la sua religione e a cristianizzarsi […] e poi per rendere omaggio allo scrittore Jovine che chiama il suo personaggio principale Marano ne Le terre del sacramento, quindi è un omaggio a una certa letteratura meridionalista.11 Un altro esempio è posto in bocca a un personaggio, il Madralisca del Sorriso, che chiosa il cognome di «un celebre ministro di Polizia alla corte del sovrano Ferdinando, vicarioto di nome, nonché di fatto, creduto che in vicarìa o bagno dimori malavita», con riferimento al sic. vicarioto ‘galeotto’12 e, aggiungo, etnico arcaico del paese di Vìcari alle porte di Palermo.13 – la doppia lingua, ossia il mondo reinventato attraverso la ridenominazione di ogni cosa, nei Linguaggi del bosco, grazie alla ‘selvatica’ amica Amalia: «Mi rivelava i nomi di ogni cosa, alberi, arbusti, erbe, fiori, quadrupedi, rettili, uccelli, insetti… E appena li nominava, sembrava che in quel momento esistessero. Nominava in una lingua di sua invenzione, una lingua unica e

personale, che ora a poco a poco insegnava a me e con la quale per la prima volta comunicava»;14 – addirittura si può parlare di un parallelismo tra scrittura e lettura, autore e lettore: «Io penso a un lettore che mi somigli, che sia simile a me, che abbia lo stesso tipo di conoscenza. […] Io penso a uno che sia veramente il mio doppio, che abbia la mia stessa storia, la mia stessa cultura, le mie stesse letture, che faccia parte di una stessa sfera culturale».15 In Retablo, in particolare, si muovono in parallelo: le vicende del nobile milanese Fabrizio Clerici e del fraticello palermitano Isidoro, nato Cicco Paolo Cricchiò, che viaggiano per la Sicilia insieme, per lenire le proprie delusioni amorose con un bagno di storia, rovine, cultura; le storie d’amore del Cricchiò e di Vito Sammataro, accomunati dal nome della donna amata, Rosalia; 11

C fr. Le interviste di Italialibri: Intervista con Vincenzo Consolo, cit. 12 Leonardo Terrusi, L’onomastica nel Sorriso dell’ignoto marinaio di Vincenzo Consolo, «il Nome nel testo», XIV (2012), pp. 55-63, p. 62. 13 Cfr. Teresa Cappello – Carlo Tagliavini, Dizionario degli etnici e dei toponimi italiani, Bologna, Pàtron 1981, s.v. 14 Vincenzo Consolo, Le pietre di Pantalica, Milano, Oscar Mondadori 1990 (1ª ed. 1988), p. 155. 15

C fr. le interviste di Italialibri: Intervista con Vincenzo Consolo, cit.

la scrittura del diario del Clerici – il diario dedicato da Fabrizio all’amata doña Teresa – sul retro dei fogli dove suor Amata di Gesù, al secolo Rosalia Granata, narra la vicenda del corrotto frate Giacinto e di Vito Sammataro; il parallelo tra seduzione amorosa e seduzione artistica della scrittura, evidenziato da Tatiana Basanti16 e ben esemplificato da Rosalia, oggetto di culto e donna amata su cui convergono i percorsi di desiderio dei vari personaggi i Retablo; la duplice lettura del romanzo come intreccio di fughe e come ideale guida ai loca memorabilia della Sicilia occidentale, proposta da Nicolò Messina;17 lo stesso titolo, di cui disse l’A.: «La parola retablo (parola oscura e sonora, che forse ci viene dal latino retrotàbulum): il senso, per me, dietro e oltre le parole, vale a dire metafora) l’ho assunta nelle varie accezioni: pittorica, shahrazadiana, cervantesiana»,18 può essere interpretato come allusione all’organizzazione strutturale del libro, diviso in tre parti come tavole di un polittico; e come riferimento all’affabulazione letteraria e al tratto illusorio dell’arte, attraverso l’evocazione cervantina, ossia all’Intermezzo el Retablo de las maravillas che compare in una delle pagine più barocche dell’autore del Quijote.19 Viene spontaneo chiedersi se questa dualità, questa presenza di parallelismi, si estenda ai nomi propri. Partiamo dal protagonista della vicenda cui Consolo attribuisce il nome e il cognome, e qualche altro aspetto del comportamento e del personaggio reale, del suo amico pittore milanese Fabrizio Clerici. E qui attenzione. Lo stesso meccanismo onomastico (attinzione di una catena onimica appartenente al Clerici reale) era già stato utilizzato da Alberto Savinio in Ascolto il tuo cuore, città (1944), storia di un vagabondare per Milano dei due artisti.20 16

Cfr. Tatiana Basanti, Seduzione amorosa e seduzione artistica in Retablo di Vincenzo Consolo, «Cahiers d’études italiennes», V (2006), pp. 57-68. 17 Cfr. Nicolò Messina, Breve viaggio testuale a ritroso: i retablos di Vincenzo Consolo, «Cuadernos de Filología Italiana», IV (1997), pp. 217-249, p. 223. 18 C it. in Salvo Puglisi, Soli andavamo per la rovina. Saggio sulla scrittura di Vincenzo Consolo, Acireale (Catania)/Roma, Bonanno 2008, p. 207. 19 Pubblicato nel volume Ocho comedias y ocho entremeses nunca representados del 1615. Cfr. Stazzone, «Quel pittore…, cit., p. 80. 20 P er tacere del fatto che alcuni individuano nello stesso artista il protagonista di Todo modo di Leonardo Sciascia. Cfr. Traina, Nomi, misteri, pittori. Il punto su Todo Modo, in La bella pittura. Leonardo Sciascia e le arti figurative, a c. di P. Nifosi, Racalmuto (Agrigento), Fondazione Sciascia – Salarchi Immagini 1999, ora in Traina, Una problematica modernità. Verità pubbliche e scrittura a nascondere in Leonardo Sciascia, Acireale (Catania)/Roma, Bonanno 2009.

Ora, Savinio è anagraficamente un De Chirico, cognome barese di Terlizzi, in particolare, e balza all’attenzione l’omonimia, Clerici/(De) Chirico, che peraltro Savinio aveva già sottolineato nel 1942 scrivendo all’amico: «Tu come Clerici e io come Chirico […] siamo oltre a tutto anche parenti […] e assieme risaliamo al comune klericós e kleros, cioè a dire a quel che tocca in sorte», come riporta Paolo Mauri.21 Consolo riprende, dunque, il nome di casato Clerici prima di tutto, disse, perché aveva bisogno di un nome di antica e sicura tradizione lombarda22 e, inoltre, perché vedeva in Fabrizio «un ideale lombardo del Settecento, di quel gruppo che rappresenta il volto migliore di Milano, della sua cultura e civiltà».23 Assegna, poi, al fraticello che gli farà da guida, il nome Cicco (Francesco) Paolo e il cognome Cricchiò.

Cricchio (senza accento) è un nome di famiglia siciliano, accentrato nel Palermitano,

con presenze sparse nell’isola, che può avere varie etimologie e tra queste, rimettendoci al dizionario di Girolamo Caracausi,24 prevale il significato di clericus.25 Cricchiò nella realtà odierna sembra non esistere, ma è una variante grecizzante, presumibilmente attestata in passato e perfettamente parallela a Chiricò – catanzarese, e con un gruppo a Trabia, nel Palermitano –, al salentino Chiriacò e al catanzarese Clericò, appartenenti alla medesima famiglia onomastica. Dunque, non solo Chirico e Clerici, ma anche Clerici e Cricchiò hanno il medesimo cognome; e non la voce dell’italiano Chirico, sopravvissuta nella variante chierico e nel suffissato chierichetto, ma da un lato la forma latineggiante che ha conservato il nesso -cl-, dall’altra una voce dialettale, a siglare il contrasto di status, almeno iniziale, tra i due personaggi e a ratificare il distanziamento bidirezionale dalla lingua standard. Quanto agli altri cognomi, in Retablo, si vedano quelli delle due Rosalie: Guarnaccia, la donna amata dal fraticello Isidoro, e Granata, quella di cui s’era infatuato frate Giacinto di Salemi, protagonista di una sorta di novella boccaccesca, dove la donna fugge dopo la decapitazione del religioso che 21

Cfr. Mauri, Fabrizio delle meraviglie, cit. 22 Tra i primi 100 per frequenza in Lombardia e tra i primi 16 nel Comasco, cui si richiama nel finale di Retablo, quando incontra alcuni corregionali presso il rettorato della Nazione Lombarda di Palermo. Cfr. Enzo Caffarelli – Carla Marcato, I cognomi d’Italia. Dizionario storico ed etimologico, Torino, Utet 2008, 2 voll., s.v. 3 Cfr. Mauri, Fabrizio delle meraviglie, cit. 24 Cfr. Girolamo Caracausi, Dizionario onomastico della Sicilia, Palermo, Centro di studi filologici e linguistici siciliani 1993, 2 voll. 25 Mentre, secondo una diversa ipotesi, rifletterebbe il siciliano crìcchiu ‘cima di un monte’; soltanto s.v. Lo Cricchio, cognome altrettanto di Palermo e dintorni, Caracausi ammette una terza possibilità, e cioè da cricchio ‘capriccio’, seguendo qui Gerhard Rohlfs, Dizionario storico dei cognomi della Sicilia orientale, Palermo, Centro di studi filologici e linguistici siciliani 1984, area dove peraltro il cognome pare attestato solo isolatamente.

l’aveva più volte posseduta. Ora, Guarnaccia può interpretarsi come ‘vestito

di donna povera’,26 altro cognome trasparente e corrispondente al personaggio,

mentre Granata può derivare, sì da un nome di persona, da Granada toponimo o da granata nelle accezioni di ‘scopa’, ‘mela granata’, ecc., ma anche ‘pietra preziosa di colore rosso vinato’.27 E in tal caso ci troveremmo di fronte a un’ulteriore dicotomia – povertà e ricchezza – che corre in parallelo tra le pagine di Retablo. Mentre il cognome di Cristina Insàlico, madre di Rosalia Guarnaccia, variante del più diffuso Insàlaco, dall’arabo sallāq, ‘conciapelli, cuoiaio’, non comunica nulla sui genitori della fanciulla, diverso può essere il caso di Affronti, ossia don Gennariello, già cantante (voce bianca) e ora maestro di canto di Rosalia, che vive, mantenuta da un vecchio marchese, in regime di castità; Affronti è cognome raro e palermitano dalla voce siciliana affruntu ‘disonore, vergogna’:28 forse un’allusione alla castrazione giovanile della voce bianca? Lo stesso vale per don Vito Sammataro, che per amore dell’altra Rosalia, la Granata, aveva ucciso ed era divenuto brigante. Sammataro è cognome raro dell’area tra Palermo e Messina e corrisponde al siciliano zambataru, ‘mandriano, addetto alla custodia e alla cura delle vacche di una cascina, e alla raccolta e lavorazione del latte’, calabrese sambataru, ‘capo di una mandria’;29 nel nostro caso lo si più leggere come un nome parlante, se per mandria intendiamo anche ‘banda di briganti’, piuttosto sbandati, come quella guidata da don Vito. Quanto ai nomi personali dei protagonisti, Fabrizio in letteratura sa di nobiltà e cultura forse per il ricordo di don Fabrizio Corbera, principe di Salina, del Gattopardo, forse perché, come notato da Paolo Mauri,30 il Clerici pare il sosia di Fabrizio del Dongo, nobiluomo milanese (anche la figura stendhaliana è protagonista di viaggi e fughe, e si noti che, nel coniare un cognome di fantasia, Stendhal dovette ispirarsi al toponimo Dongo, comune del Comasco, e Clerici è cognome tipicamente comasco).31 Il nome personale con cui il Cricchiò è citato nel racconto è, però, quello assunto una volta indossato il saio, e cioè Isidoro, ‘dono della dea Iside’. Esso induce a correre il rischio di una superinterpretazione: si presenta etimologicamente come profano e pagano, avendo Iside quale eponimo, ma anche come nome della cristianità, grazie ai tanti santi, Isidoro di Siviglia in

26 Cfr. Caracausi, Dizionario onomastico della Sicilia, cit., s.v.

27 Cfr. Caffarelli – Marcato, I cognomi d’Italia…, cit., s.v.

28 Cfr. Dizionario onomastico della Sicilia, cit., s.v.

29 Ivi, s.v. 30 Cfr. Mauri, Fabrizio delle meraviglie, cit.

31 I l Fabrizio personaggio vanta dei parenti dalle parti di Stazzona – citato in Retablo come luogo di partenza di alcuni emigrati in Sicilia (p. 104).

primo luogo, che lo hanno portato. Del nome anagrafico abbiamo notizia

in due soli casi, se ho ben letto: nell’ultimo elemento del trittico, «Veritas»,

così richiamato dall’amata Rosalia, e quando Isidoro e Fabrizio si presentano

al curatolo Nino Alàimo senza borse né abiti, perché aggrediti e spogliati d’ogni cosa dai briganti. Come a dire che il nome di nascita emerge esclusivamente nei momenti di ‘nuda verità’. Se consideriamo il nome anagrafico del monachello-guida, il doppio Francesco Paolo, si tratta, al contrario di Fabrizio, di un nome popolare, nella sua doppia accezione: da un lato, di ‘popolano’ – appartenente al popolo e al culto vivissimo in Sicilia per il calabrese San Francesco di Paola –, e dall’altro lato di ‘diffuso’, perché nell’antroponimia isolana spicca con le sue elevate frequenze.32 Popolano, dicevo, tanto più che nel racconto è soltanto Cicco Paolo, cioè un ipocoristico (il primo elemento) che è, sì, fungibile per l’uso vezzeggiativo indipendente dal nome base, ma in Sicilia non difficilmente ricollegabile a Francesco.33 Si noti peraltro la doppiezza di Francesco Paolo, caso davvero raro di toponimo (Paola) adattato ad antroponimo con cambiamento di genere e con naturalezza, perché l’esistenza del latino Paulus copre la trasparenza del processo transonimico (e che peraltro cela a sua volta l’etimologia del toponimo, non un deantroponimico, in quanto deriva dal sostantivo plurale pabula ‘pascoli’ o da terra pabula come aggettivo singolare). Basterebbe comunque l’incipit dell’«Oratorio» di Retablo per convincersi che il nome proprio è parte integrante delle attenzioni ‘espressionistiche’ di Consolo. Si potrebbe scrivere un ampio saggio esclusivamente su questo incipit e sul nome Rosalia, che ha qualche precedente, ad es. l’elaborazione

petrarchesca di Laura e quello della Lolita di Nabokov (1955). Ne riporto (con qualche omissis) alcune righe. A parlare è l’ex frate Isodoro: Rosalia. Rosa e lia. Rosa che ha inebriato, rosa che ha confuso, rosa che ha sventato, rosa che ha róso, il mio cervello s’è mangiato. Rosa che non è rosa, rosa che è datura, gelsomino, bàlico e viola; rosa che è pomelia, magnolia, zàgara e cardenia. […] Rosa che punto m’ha, ahi!, con la spina velenosa in su nel cuore. Lia che m’ha liato, la vita come il cedro o la lumia il dente, liana di tormento, catena di bagno sempiterno, libame oppioso, licore affatturato, letale pozione, lilio dell’inferno che credei divino, lima che sordamente mi corrose l’ossa […]. Corona di delizia e di tormento, serpe che addenta la sua coda, serto senza inizio e senza fine,

32 Rappresenta, unico caso nelle diverse regioni d’Italia, il nome composto più diffuso nel XX secolo, e attualmente 18º in assoluto nella città di Palermo con circa 3600 portatori (dati forniti dalle Anagrafi Comunali). 33 Ritroviamo un altro ipocoristico di Francesco in Chino Martinez, protagonista dello Spasimo

di Palermo.

rosario d’estasi, replica viziosa, bujo precipizio, pozzo di sonnolenza, cieco vagolare,

vacua notte senza lune, Rosalia, sangue mio, mia nimica, dove sei?» (p. 17). Ebbene, anche qui abbiamo quasi due lasse poetiche che corrono in parallelo, contrapposte ma complementari. La dualità nasce, prima di tutto, dalla segmentazione errata del nome, frutto di una reinterpretazione popolare, di una paretimologica interpretazione del nome francese antico Roscelin o Rocelin – a sua volta dal germanico Ruozelin/Rozelin nell’adattamento all’italiano (insieme a Rusulina), col significativo complessivo di ‘cavallo glorioso’ – come composto di Rosa e di Lia, o comunque derivato-variante di Rosa,34 il che non è (lo conferma, ove necessario, il corrispondente maschile che ha invece conservato compattamente, in Sicilia almeno, anche la nasale finale, Rosalino o Rosolino, forse anche qui per rietimologizzazione, ossia per l’interpretazione di -ino come suffisso).35 Tale processo di rietimologizzazione, a partire dall’etimo normanno, sarà stata nota a Consolo? ritengo di sì, anche se lo scrittore ha affermato di aver «scelto il nome Rosalia per S. Rosalia, ma anche per la scomposizione rosa e lia».36 Conta comunque notare come Rosa e Lia diano vita a una serie di allitterazioni in parallelo, dove Rosa gioca un ruolo positivo per l’innamorato e Lia un ruolo negativo; anche in alcune battute i ruoli s’invertono e alla fine si ricompone il nome intero nel segno del proprio sangue e dell’inimicizia. In questa scomposizione del nome palermitano di donna per eccellenza, anche nome della sua generazione,37 lo scrittore compie un’operazione di acrobazia espressionistica, ma non spregiudicata, perché legittimata dalla secolare rifondazione popolare del significante, benché non dall’etimo. La scrittrice e saggista caltagironese Maria Attanasio ne dà una convincente interpretazione quando afferma che Consolo scava «nelle sonorità del nome Rosalia, trovando in esso occultati tutti i sensi e i segni della passione. Ognuna delle due parti del nome genera infatti una appassionata proliferazione di figure d’amore, se ‘Rosa’ è l’immaginifica sorgente di tutti [i] fiori, i colori,

34 Precisa Emidio De Felice in proposito che Rusulina per influsso di Lia «si è trasformato in Rusulia e quindi, per un accostamento dovuto a etimologia popolare a Rosa e rosa, nella forma italianizzata Rosalia attuale» (Dizionario dei nomi italiani, Milano, Oscar Mondadori 1986). 35 Rosalino La Rosa è un personaggio di una novella di Pirandello, Le medaglie (1923). 36 C fr. M. De Martino, Intervista a Vincenzo Consolo, nella dissertazione L’opera di Vincenzo Consolo (presentata alla University of Alberta), 1992, pp. 35-49, p. 48. 37 Rosalia, patrona del capoluogo siciliano, era al rango 2 nel 2014, dopo Maria, tra le siciliane oggi viventi residenti in Palermo, e al r. 2 nell’analisi sincronica dei nati anno per anno per quasi tutto il secolo; attorno agli anni 40 la forma assurse addirittura al rango 1, con una frequenza pari al 10% del totale delle nuove nate (elaborati su dati forniti dall’Anagrafe del Comune di Palermo).

gli aromi, di tutte le sfumature di bellezza dell’nata […] il ‘li’ di ‘Lia’ invece

si moltiplica in una spirale di indicibili tormenti amorosi».38 E questo incipit fa vibrare la ricchezza dei predicati, puntualmente inanellati con preziosi attributi, talora con suggestioni omofoniche anche se non corradicali (‘rosa che ha roso’), contrasti semantici (‘rosa che è… viola’), allitterazioni e rimandi fonetici (‘lia… liana… libame… licore… lilio… lima… limaccia… lingua… lioparda… lippo… liquame…’) fino al verbo liare (‘m’ha liato la vita’) che vale ‘legare’ e di cui lia costituisce la terza persona singolare del presente. Rosalia è dunque il nome femminile che pervade pressoché ogni pagina del romanzo di cui ci stiamo occupando, presente ovunque anche nella letteratura siciliana: lo stesso Consolo se n’era servito nel suo romanzo d’esordio, La ferita dell’aprile (1963), per la sorella della baronessa Ninfa e di don Mimillo. L’omonimia delle donne amate è smaccata e trasparente, ma anche realistica. Tuttavia quando, tra echi d’amore, Isidoro e Vito Sammataro credono di riconoscere ciascuno la propria amata nel disegno che per Fabrizio rappresenta invece la ‘sua’ Teresa Blasco, la figura incarna «solamente la

Rosalia d’ognuno che si danna e soffre, e perde per amore» (p. 66). E allora Rosalia si fa quasi antonomasia e nome comune, una sorta di deonimico ideale, per indicare un qualsiasi oggetto femminile d’amore. E nello stesso tempo, ancora in parallelo, Rosalia è nome misterioso per Fabrizio, che non intende come possa ossessionare da sveglio e da dormiente il fido fraticello che lo guida nel viaggio di fuga e di dimenticanza: – Isidoro, – gli dissi resoluto – tu mi devi finalmente disvelare il mistero che nasconde questo nome: Rosalia! – Eccellenza, eccellenza, mi lasciasse al mio rimorso e al mio tormento… – implorò quegli. Ma io mi feci più imperioso e più insistente. E allora quel tapino cominciò a parlare, a sospirare, ma le parole, incompiute, rotte, annegavano in un mare di sospiri. […] Rosalia è l’angelo più bello che sta in cielo… No, è ’na diavola! (p. 39) Il nome proprio si fa così oggetto di discussione e motore d’azione e ancora una volta stimola, nell’innamorato, sentimenti fortemente contrastanti. Sono dunque numerose le piste che portano a individuare una varietà di significati nei nomi opposti e paralleli del Consolo di Retablo. Ma la ricchezza dell’antroponimia e della toponimia del racconto non si esaurisce qui. Ricchezza che è data sia dal ricorso a voci arcaiche, appartenenti a più lingue

38 Maria Attanasio, Struttura-azione di poesia e narratività nella scrittura di Vincenzo Consolo, «Quaderns d’Italia», X (2005), pp. 19-30, p. 24.

e dialetti (il plurilinguismo dei nomi propri); sia dall’uso narrativo, attraverso dittologie, terne e accumuli, che si fanno inventari preziosi, articolati su colori, sapori, profumi, complementi di materia,39 o elaborazione fonetica di singoli nomi in allitterazioni insistite, come per il nome Meli di un poeta incontrato da Fabrizio e Isodoro: «Ma Mele dico ei doversi dire, come mele o melle, o meliàca, che ammolla e ammalia ogni malo male», p. 55; e, per il brigante inteso Trono: «Trono, trono che introna e allampa», p. 63. Ancor più gli accumuli si fanno frequenti e ampi in àmbito toponimico: nomi rari, antichi e preziosi, legati comunque alla realtà del viaggio, come Burghetto, Bagni Segestani, Gàggera, Calèmici, Ràbisi, Gibèli, Rapicaldo, Mokarta, Settesoli, Campobello, Rodi Mìlici, Montevago, Zabut, Simplegadi,

Belìce, Melos, Sabatra, Maràusa, Levanso, Bonagìa, la Gerba e Gabès, Kelibia

e Karkenna, Dàttilo, Nàpola; alcuni arcaismi paiono fin troppo ricercati, come Lilibeo e Panormo, altri lo sono sul piano fonetico (Bagarìa, Favognana, Pertenico). Alcamo diventa la «terra di Halcamah» (p. 29).40 Da notare i nomi stranieri a volte adattati – così Shakespeàro e Winkelmano, p. 90 – e i toponimi sono anche nei titoli che suddividono la «Peregrinazione » del racconto: ‘Nel paese di Halcamah’, p. 29, ‘In Selinunte greca’, p. 66, ‘In Mozia de’ Fenici’, p. 81, ‘In Trapani falcata’, p. 91, ‘In Palermo’, p. 102; e anche il primo titolo, dopo la breve ‘Dedicatoria’, contiene un naonimo, ‘Sull’Aurora, all’aurora’, p. 28, il battello da cui Fabrizio sbarca a Palermo. I nomi propri, ma in questo caso al pari delle voci di lessico, danno inoltre l’opportunità di misurare i tratti dialettali della prosa di Consolo. E alcuni esempi paiono confermare che siamo di fronte più a una koiné siciliana ai limiti dell’italiano regionale, dato che i tratti rappresentati in Retablo non identificano alcuna precisa area linguistica all’interno dell’isola,41 con due eccezioni: il rotacismo di laterale preconsonantica (Arcamo ‘Alcamo’, p. 35) nel parlato del Soldano, tratto proprio della sezione occidentale dell’isola in cui si svolge il racconto; e l’assimilazione in Lombaddia, p. 50 (a parlare è un brigante del Trapanese, mentre il palermitano Isidoro pronuncia nella battuta precedente «Lombardia»), come pure il cavalier Serpotta citato dal 39

C fr. anche Gianluca D’Acunti, Alla ricerca della sacralità della parola: Vincenzo Consolo, in Accademia degli Scrausi, Parola di scrittore. La lingua della narrativa contemporanea dagli anni Settanta a oggi, a c. di V. Della Valle, Roma, Minimum Fax 1997, pp. 101-116. 40 E per «i fastosi cataloghi o elenchi di toponimi, spesso accostati in asindeto puro, privi finanche di virgole separative, che caratterizzano la tessitura del Sorriso oltre ogni ragionevole istanza descrittiva o realistica», rimando a Terrusi, L’onomastica nel Sorriso dell’ignoto marinaio…, cit., p. 59.41 M i sono fondato su Alberto Varvaro, Italienisch: Areallinguistik XII. Sizilien, «LRL», Tübingen, Niemeyer 1988, vol. VI, pp. 716-731; e sulle isoglosse in Ruffino, Dialetto e dialetti di Sicilia…, cit.

sultano Lodovico come Seppotta, p. 36, esiti questi assai meno ovvi a occidente. 42

Ancora sul piano stilistico, in una prosa costellata di metafore e comparazioni, i nomi propri sono sovente i referenti. Solo per citarne alcune, dal mondo classico: «spavaldo e paonante, credendosi un Medoro», p. 39, «bella come la caprigna figlia di Melisso», p. 56, «come la testa mozzata del Battista offerta a Salomè», p. 84, ecc. – ma anche calate nella cultura, nel costume e nella storia locale: «carico come uno sceicco di Pantelleria», p. 19, «figlia pare del principe di Butera o Resuttana», p. 20, «mi parvi preso da’ turchi, da’ corsari», p. 22, «biondo e rizzuto come un San Giovanni», p.

109, «torvo, nero come un san Calogero», p. 109, ecc. Poi ci sono i soprannomi, dove lo sfoggio onimico è in piena armonia con l’autocompiacimento linguistico complessivo: don Vito Sammataro inteso Trono, i suoi ‘compagni antichi’ Sciarabba e Fulgatore, il corsaro saracino Spalacchiata, Crisèmolo, Calòrio, ecc. E gli pseudonimi dei membri dell’Accademia de’ Ciulli Ardenti: Abelio Zenòdoto per don Erminio Chinigò, Aristeo Apollonio alias don Getulio Camàro. Di un certo interesse è l’uso frequente di un doppio allocutivo: «Amabilissimo signùre, cavalère Clerici», p. 35, «Cavalère, maestro don Fabrizio», p. 36, «Cavalèr Soldano, don Lodovico», p. 40, «Andate, andate via subito, signor Maestro Clerici, andate, don Fabrizio», p. 101, «Don Fabrizio, signor don Fabrizio Clerici», p. 104, «Addio Teresa Blasco, addio marchesina Beccaria», p. 105. Consolo non si ferma neppure dinnanzi alla spiegazione etimologica, se questa gli offre l’opportunità di giocare con le parole, come quando, giungendo al villaggio, Vita scrive: «Vita che non dalla vita prese il nome, ma da un tal Vito come il Vito nostro Sammataro, che poi è nome che dalla vita viene» (p. 67): una sintetica ricostruzione di un processo lessiconimico e transonimico relativo a Vito Sicomo, esimio giureconsulto che fece costruire

il primo nucleo dell’attuale comune del Trapanese. I nomi sono anche richiami intertestuali: quanto c’è di voluto nel mettere insieme Lorenzo e Lucia, il primo, un giovane di Stazzona, comune comasco, trasferitosi con la famiglia a Palermo, la seconda, destinataria di un dono di orecchini affidati al Clerici dallo stesso ragazzo? In conclusione, il nome proprio dà in modo evidentissimo il suo contributo a questa lingua di Consolo, che per Renato Minore mette insieme l’ansia 42

La pronuncia assimilata di liquida più consonante è propria della Sicilia orientale, ma si riscontra sporadicamente anche a Cefalù e a Sciacca (Ruffino, Dialetto e dialetti di Sicilia…, cit., p. 112). Per altre deformazioni popolari rimando a Terrusi, L’onomastica nel Sorriso dell’ignoto marinaio…, cit., p. 57.

di conoscenza di Sciascia e il violento plurilinguismo di Gadda e per Stefano Giovanardi è «musicale e misteriosa, attorta su termini rari e preziosi e poi

improvvisamente sciolta con ritmi di sistole e diastole nel giro del parlato