C’è un punto nella vita in cui le seduzioni della realtà, della memoria, dei libri, si moltiplicano, diventan tante; in cui si vorrebbe dir tutto di quel che alla mente si affaccia di non ancora detto (che, si capisce, già è stato detto), di nuovo (che, si capisce, è già antico); ed è il punto stesso in cui sentiamo che non abbiamo più tempo.

Leonardo Sciascia, Per un ritratto dello scrittore da giovane

(cessa, la condizione di poeta,

quando il mito degli uomini

decade… e altri sono gli strumenti

per comunicare con uomini simili… anzi,

meglio è tacere, prefigurando

in narcissico sciopero, l’ultima pace)

Pier Paolo Pasolini, «L’alba meridionale», Poesia in forma di rosa

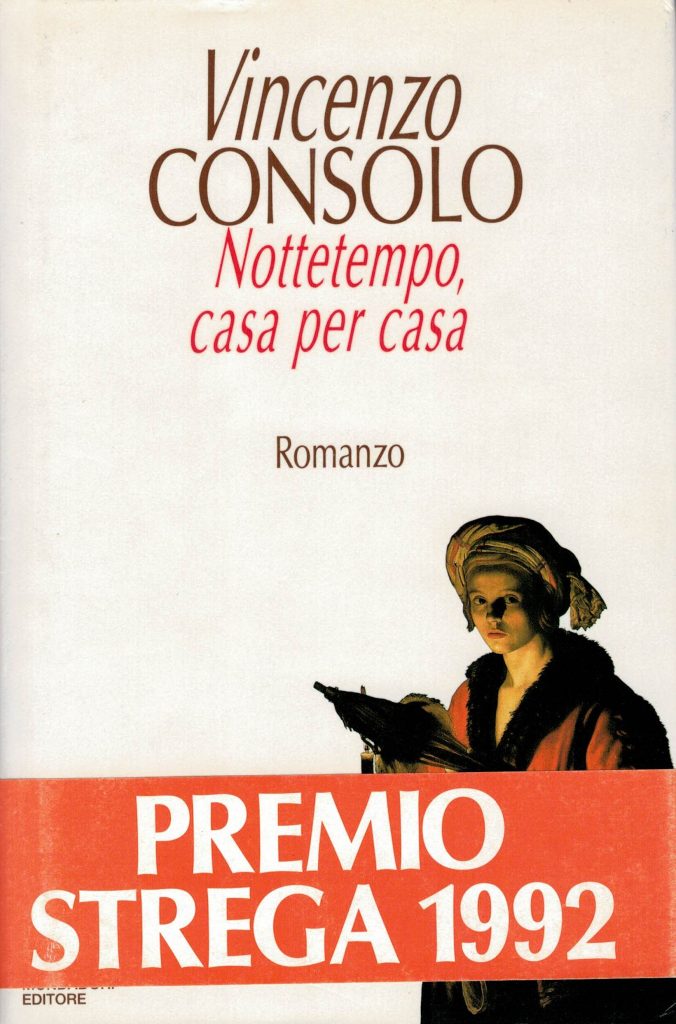

Quando mi è arrivato nelle mani, appena uscito, Lo Spasimo di Palermo, ha subito richiamato la mia attenzione la copertina, anzi un suo particolare: un piccolo riquadro che incornicia un volto scomposto, una bocca spalancata che urla, ma ritraendosi quasi; si tratta come sappiamo di un dettaglio del dipinto di Raffaello Sanzio Gesù caduto sul cammino del Calvario, e raffigura uno sbalordimento che si scaglia come voce sconnessa, grido: quindi un rumore assordante che traffigge e annulla ogni umana conversazione, rotto ogni avverarsi della parola scandita davanti allo scandalo della violenza. Certo a conti fatti – cioè a lettura finita, ma soprattutto col senno di poi – era su questa dimensione che immetteva la veste del libro: il testo, e con uno sguardo retrospettivo l’intera opera di Vincenzo Consolo, lo conferma.

Avevo letto Il sorriso dell’ignoto marinaio quando apparve in spagnolo, nei primi anni ottanta, e avevo colto la tensione che, già da questo secondo romanzo, impregna la scrittura consoliana verso «la dimissione, l’abbandono della penna», come si leggerà poi nell’ultimo, definitivo romanzo della «sconfitta» (Spasimo, X). Quando, alla fine dei novanta lessi o rilessi tutta l’opera, scrissi un breve saggio nel quale parlavo della dimensione metafinzionale della sua narrativa, di quel far ruotare il racconto attorno al perno dello stesso suo farsi, anzi del suo essere possibile, della sua liceità. Mi auguravo che a dispetto del mutismo coatto, e dal proprio smarrimento e dalla assenza del destinatario, pur nella «cavea… vuota, deserta» (Metrica), il narratore, il dicitore ritrovasse ancora la spinta appunto a dire.

Quel saggetto (dopo essermi consigliato epistolarmente con Nicolò Messina, professore allora a Santiago del Cile, i cui saggi sul Sorriso avevo letto ma che non conoscevo ancora di persona), lo mandai a Vincenzo nel maggio del 2000, accompagnato da una lunga lettera nella quale alludevo alle foscoliane «corrispondenze» tra lui scrittore ed io lettore e mi soffermavo (leggo da quella prima lettera) sul suo “modo di nominare malgrado la tentazione (si direbbe quasi dannazione) del silenzio: il raccontare di fronte all’imposizione dell’assenza della storia, alla moltiplicazione delle false parole che ingombrano la memoria”; e poi, rifacendomi a Per una metrica della memoria, appunto, gli scrivevo del suo ragionare su un narrare “che sfocia nell’arresto, l’afasia”.

Mi rispose nel luglio, in una altrettanto lunga lettera, dattiloscritta, ma con l’intestazione a mano (“Gentile professor Cuevas, caro Miguel Ángel”); un dono, che io non lessi se non al rientro a Siviglia dopo l’estate siciliana: “rispondo dopo più di due mesi alla sua lettera. Me ne scuso, e non metto in campo banali, quotidiane difficoltà, restrizione del tempo, ma solo questo motivo: lettere come la sua mi spiazzano, mi fanno sentire incapace di rispondere nei veri e giusti termini, e allora rimando… Insomma, quanto più si è affabili con me, pazienti, attenti e intelligenti nel leggere e decifrare le mie oscure peste (orme, ma anche segni appestati), tanto più io fuggo, mi nascondo. Fine della confessione.” La lettera si chiudeva con una vera e propria, e articolata, dichiarazione di poetica: “Certo, impressiona la corrispondenza tra la mia «auto» e la sua interpretazione. Lei ha capito come nessuno che da quasi quarant’anni scrivo con la consapevolezza – man mano sempre più chiara, lucida – e insieme con l’angoscia di trovarmi all’estremo, al margine, in un luogo e in un tempo di confine o di fine: sull’orlo, per intenderci, di un precipizio, al tramonto, alla fine di un tempo, di una civiltà. Da qui dunque lo sgomento e lo smarrimento; da qui la tentazione del silenzio e insieme il bisogno e il dovere di dire, di testimoniare; da qui il declamare o cantare come una trenodia o epicedio, da qui l’espressivo-poetico… E ancora: i vari libri che formano un unico libro (la concatenazione quindi fra loro e la loro conseguenziale necessità): il macrotesto con la circolazione o insistenza in esso di «temi» e «toni», con le autocitazioni, con la scrittura e metascrittura, con l’insistenza sulla memoria (personale e letteraria), sentendo prossima la sua cancellazione… Ma forse è stato sempre così per ogni scrittore o poeta d’ogni luogo e d’ogni tempo, così, intendo, nell’avere il senso doloroso d’una fine. Ho scritto nella mia operetta Lunaria: «Ogni fine è dolore, smarrimento ogi mutazione, stiamo saldi, pazienza, in altri teatri, su nuove illusioni nascono certezze».” E concludeva: “So, d’ora in poi, d’avere un «corrispondente»” in terra di Spagna.”

Ma questa risposta potei leggerla solo a settembre. Nell’agosto, la nostra comune amica Maria Attanasio (appena ritrovata a Catania, dopo quasi quindici anni in cui ci eravamo perse le tracce) mi disse di aver sentito Vincenzo, che mi avrebbe ricevuto volentieri a Sant’Agata di Miltello. Ma io, prima di conoscere lo scrittore di persona, avevo bisogno di un suo riscontro scritto, e quindi non lo andai a trovare.

Sulla mia scrivania, nell’ufficio all’università sivigliana, una busta di quelle che già allora non si usavano più, con i colori azzurri e rossi della «posta aerea». Finalmente. Quindi la mia risposta, nella quale mi azzardavo addirittura a parlargli, rotto da lui il ghiaccio, spinto a rimuovere il velo della timidezza, della sua Sicilia: “Catania nera e rosea di sabbie laviche, le distese sotto Enna gialle di spighe riarse, il tufo ocra della Valle dei Templi, Mozia soltanto adesso conosciuta – riconosciuta però con Fabrizio Clerici viaggiatore. Ma accanto al candido del sale anche i rifiuti, insieme al piccolo borgo il veleno delle ciminiere di Milazzo, Porto Empedocle in controccanto al Tempio della Concordia. E i vicoli di Caltagirone con Maria Attanasio, il caseggiato al tramonto dalla Via del Re, Siracusa nella luce decapitata dei cordari di Caravaggio assieme al volto in decomposizione del vescovo baconiano, i sepolcri aperti alla strage, l’Anapo che lambisce le ceneri d’oro di Pantalica… Ho rigirato l’Isola, come vede, in compagnia delle sue parole”.

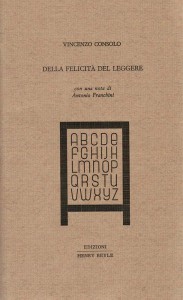

Le lettere scarseggiano da quando ci siamo conosciuti personalmente l’anno successivo: ci si incontrava spesso, a Milano, in Sicilia, qualche volta in Spagna; ci sentivamo per telefono; pure, purtroppo, è subentrata nel colloquio la posta elettronica. Qualche avanzo del passato, qualche rudere resta però. In risposta al regalo del prezioso libriccino La grande vacanza orientale-occidentale, nel novembre 2002 gli scrivevo: “C’è tutto Consolo dentro quelle poche parole: il paesaggio della Ferita, la parete, il sipario delle montagne, la marina; anche il viaggio del Clerici – e non solo per Mozia de’ Fenici – in «quella terra come una infinita teoria di rovine»; la ‘minima moralia’ del diario de L’olivo e l’olivastro nella «landa priva dei segni del tempo, ma che conteneva ogni tempo»; la storia come metafora del Sorriso, il dubbio, smarrimento: «È crudeltà, massacro, orrore dunque la Storia? O è sempre un assurdo contrasto?» Le delicate allusioni, i lievi lumi dei suoni, le parole evocate: il «porto sepolto». E poi la lingua: quella lingua visiva che preferisco dire nominazione: ecco, nel nominare, nella sosta, nel fissare attraverso il nome più che nel racconto sta la poesia schietta e alta della tua scrittura: non un verbo, non un’azione, ma neanche una visione, una descrizione: il nome invece: «Una costa diritta, priva di insenature, cale…»”

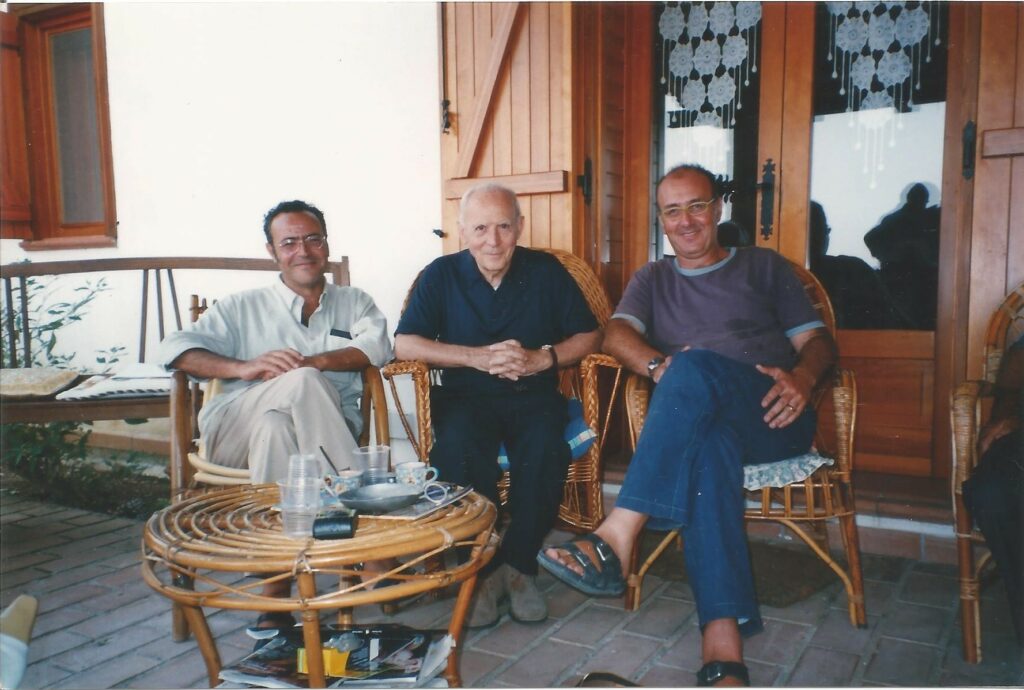

Poi avrei tradotto in spagnolo questo racconto, così come La ferita dell’aprile, Di qua dal Faro, La Sicilia passeggiata, Conversazione a Siviglia. La nostra amicizia si rinsaldava con il cemento del rispetto filologico, e dava però luogo a delle occasioni private, brevi viaggi, gite improvvise, passeggiate, tavolate condivise, sfoghi verbali di rabbia dinnanzi a quello che l’amato Pier Paolo Pasolini chiamava il qualunquismo dell’«uomo comune». Un aneddoto per tutti. Si stava andando a pranzo da Tano Grasso nella sua campagna sopra Capo d’Orlando. In macchina c’era pure Giuseppe Di Maio, regista documentarista siracusano che quella mattina dell’agosto 2005 avevo accompagnato a incontrare lo scrittore a Sant’Agata di Militello. Oltrepassata la casa dei Piccolo di Calanovella la strada si fa a tornanti, sempre in salita. A un certo punto Vincenzo frena bruscamente, fissa un figuro sulla cunetta, più in alto, si toglie gli occhiali da sole, li sbatte contro il cruscotto, mi dice: “Guida tu, per favore. C’è lassopra quello, che aspetta per darmi una mano, ché io con queste curve non ce la farei da solo. È bravo lui, e tanto gentile, sai?”

Con Giuseppe, quel mattino di agosto, eravamo reduci di una nottata al sereno a Castel di Tusa. Eravamo partiti da Catania qualche giorno prima, in macchina, alla volta di Scopello dove avremmo raggiunto Nicolò, al baglio dell’amico Tullio. Scesi nella tonnara sotto il baglio, salimmo sul vecchio piccolo peschereccio di Tullio, costeggiammo verso Castellammare. Dopo un po’, il padrone gettò l’ancora a un cinquanta metri dagli scogli e ci invitò a raggiungerli a nuoto: una piccola apertura, che bisognava oltrepassare abassando quasi la testa dentro l’acqua, immetteva in un’immesa grotta, che dall’altissima volta filtrava una luce irreale s’un acqua trasparente, sui fondali cilestri. Tornati nel baglio, a cena, pesci e vini ottimi ed abbondanti.

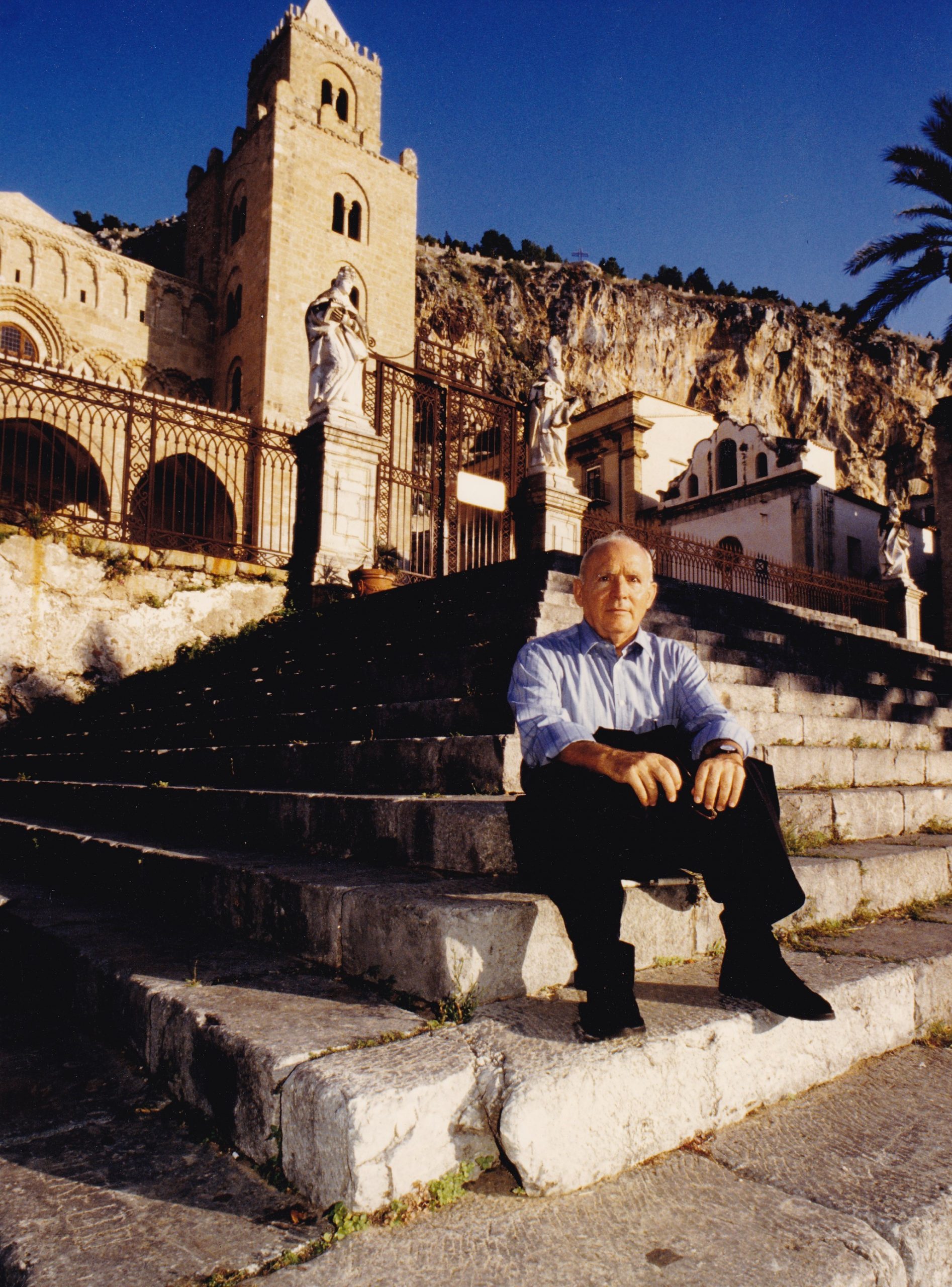

C’era però da fare parecchia strada prima di arrivare a Marsala, dove ci ospitava Nicolò. Giuseppe, facendo valere la sua condizione di fratello nico, dormiva, e a momenti quasi anch’io, che dovevo invece guidare. L’indomani riprendemmo viaggio. Dovevamo incontrare Vincenzo l’indomani ancora, e così ci fermammo a Tusa, da amici: che non ci seppero dare niente di meglio per dormire che due sdraio, su un lido, alla marina. Ci svegliò il sole, sulle pietrebambine di darrighiana memoria, di fronte alle Eolie, le «isole dolci del dio» di colui che Pier Paolo Pasolini, in una lettera degli anni ’40, chiamava «pugnettario delle parole». Risalimmo in macchina e ci incamminiamo verso Sant’Agata di Militello. Ci sbarbiamo alla menopeggio in stazione e ci presentammo nella casa dello scrittore. Giuseppe, alle prese con le sue ricerche sulle feste padronali isolane, ne avrebbe ricavato la testimonianza di Vincenzo: che, mordendosi con quel suo gesto caratteristico il labbro inferiore, mi invitò a fare una passeggiata nel paese mentre loro due parlavano di quel che dovevano parlare. C’è attestazione audiovisiva di quell’incontro tra lo scrittore e il documentarista, ma non è stata mai resa pubblica. La registrazione, una ventina di minuti, parte ex abrupto, senza alcuna domanda. L’inquadratura è sempre la stessa: Vincenzo seduto nel divano del soggiorno, qualche incisione antica sul muro dietro a lui, e in un angolo il piccolissimo Cristo ligneo seicentesco che conoscono i frequentatori della casa di Sant’Agata, trovato in qualche paese sperduto sui Nebrodi. Ripreso di mezzo busto, lateralmente, non guarda la cinepresa, gesticola poco, tranne quando la testimonianza finisce col diventare conversazione, momenti in cui fissa l’operatore. Eccone il montaggio verbale delle riprese più salienti:

«Nella mia infanzia, adolescenza, non ho memoria di particolari feste religiose, qui nel mio paese, perché è un paese giovane, e quindi si è formato, diciamo, in tempi relativamente recenti. È un paese de pescatori, di contadini, e non avevano delle grandi tradizioni di feste popolari. Ma quando ho preso consapevolezza del luogo dove abitavo, cioè della Sicilia, e ho cominciato a girare, a inoltrarmi in questi paesi dei Nebrodi, che sono dei paesi con antica storia, ho incominciato a vedere le prime feste religiose: per esempio la festa di SanFratello, dei Giudei, durante le Settimana Santa; e poi la festa di San Giovanni ad Alcàra Li Fusi, che va sotto il nome della festa del Muzzuni; la festa di San Calogero a San Salvatore di Fitalia… Ma sempre qui, in questa zona dei Nebrodi. A San Marco d’Alunzio c’erano anche la festa di San Luca, la festa dell’Aracoeli, cogli incapucciati.

»Poi, quando incominciavo a frequentare le altre parti dell’Isola, la Sicilia occidentale, la Sicilia orientale, e sopratutto quando ho conosciuto Leonardo Sciascia e andavo a trovarlo a Caltanissetta, allora ho visto la festa delle Vare del Giovedì Santo. Mi ricordo che la prima volta che ho assistito a questa festa c’era, ospite, una ragazza tedesca, che stava facendo la tesi su Leonardo; abbiamo assistito da un b alcone alla festa, e alla fine Sciascia ha chiesto a qusta ragazza: ⸺Cosa te ne sembra? — e lei, da perfetta tedesca, ha detto: —Mi sembra un po’ troppo disordinata.

»Disordinata perché questi portatori delle vare, naturalmente, alzavano un po’ il gomito, bevevano… Poi siamo andati a vedere il Venerdì Santo la festa a…»

In questo momento, sorridendo, persa forse ogni minima concentrazione nel ricordo cordiale dell’anedotto, taglia Vincenzo: «Ecco, mi sono inceppato, scusami». Si ferma la registrazione; riparte, e dopo un «Via!» di Giuseppe, riprende Vincenzo:

«Dopo la festa chiassosa, diciamo, siamo andati il giorno dopo a vedere la processione del Venerdì Santo a Enna, che è una festa severa, con queste donfraternite di incapucciati, con i simboli della Passione, che si svolgeva nel silenzio più assoluto, con queste nebbie di Enna che calavano: era veramente una visione suggestiva, una festa diciamo un po’ di tipo sivigliano, con queste tuniche bianche e questo capuccio in testa… Ci accompagnava a volte, c’era con noi in queste feste il giovane Ferdinando Scianna, che incominciava allora a fotografare le feste religiose, e da lì poi scaturì il libro che fecero assieme con Sciascia, appunto sulle feste religiose in Sicilia… Poi, naturalmente, ho visto altre feste, la festa di Trapani, le vare bellissime, tutte monocrome in legno scolpito, del Seicento…»

Lo scrittore fa un breve silenzio; e continua: «Nei miei libri, questa esperienza e conoscenza delle feste religiose, nei miei libri narrativi ma anche saggistici, ci sono pagine dedicate a queste feste. Conoscevo poi, naturalmente, i varo folcloristi siciliani, dal Pitrè a Salomone Marino e tutti gli altri. E ho trasferito, a partire dal mio primo libro, La ferita dell’aprile, il momento dello snaturamento, diciamo, e della trasformazione, nel subito dopoguerra, della festa dei Giudei di San Fratello: dove racconto che questi giudei, che erano, che rappresentavano gli antagonisti, gli uccisori di Cristo… ed erano i pastori, i contadini che recitavano questa parte, con questi costumi diavoleschi… erano gli antagonisti di una società, diciamo, più abbiente, i proprietari terrieri… Infatti, in anni lontani questi giudei diventavano anche violenti, perché compivano delle vendette, con delle catene che tenevano in mano, approfittando del fatto che erano mascherati… Ho raccontato appunto di loro, quando alle prime elezioni siciliane del ’47 sono stati portati giù, alla marina come si dice da noi, e usati per fini elettorali: insomma, questi giudei, sviliti, sono stati trasformati in propagandisti elettorali, distribuivano dei volantini per i vari candidati. E mi sembrò il primo svilimento di una tradizione popolare antichissima. Poi anche in altri libri ho raccontato delle feste religiose in Sicilia, dalla Sicilia passeggiata sino allo Spasimo dei Palermo, in cui racconto della visita che fa il protagonista Gioacchino Martinez con la moglie a Enna, dove assistono appunto alla processione degli incappucciato del Venerdì Santo… Un anno ho partecipato anch’io al Festino di Santa Rosalia, a Palermo: ho scritto un testo sulla peste di Palermo del 1623…»

E qui Vincenzo, facendo ancora un silenzio, fissa Peppe con gli occhi spalancati, l’unica volta che questo gesto si presenta in tutta la registrazione: a sottolineare inconsapevolmente quella storia, che avrebbe dovuto essere la cornice del romanzo mai scritto, Amor sacro e amor profano, del quale restano appunto quelle poche pagine pubblicate in occasione del Festino palermitano del 2002, e qualche appunto sparso qua e là. E procede:

«La scoperta della Santa sul Monte Pellegrino, insomma tutte le vicende che conosciamo, che sono fra la storia e la leggenda. Quello che sempre mi ha incuriosito è che non c’è una festa popolare per San Benedetto che viene chiamato da Palermo. È un santo questo… era figlio di uno schiavo di San Fratello, era anche lui eremita sul Monte Pellegrino, è stato beatificato. Ma quando c’era la peste a Palermo c’e stata una lotta fra francescani (questo frate era francescano) e gesuiti, per nominare, diciamo, il protettore della città. Vinsero i gesuiti, e allora fu inventata (dico inventata nel senso di inventio) la Santa Rosalia: furono scoperte le ossa sul Monte Pellegrino e quindi la Santuzza divenne la santa protettrice di Palermo. San Benedetto, sconfitto, venne dal re di Spagna esportato in Sudamerica, naturalmente con intenti politici, per tenere buone le popolazioni di colore. Questo santo è molto popolare in Argentina, in Perú, in tutta l’America Latina. E quel quartiere di Borges, che lui chiama Palermo, in effetti è San Benito de Palermo, intitolato appunto a questo santo negro, a questo santo schiavo che viene proprio da San Fratello, beatificato per il suo essere stato eremita sul Monte Pellegrino. Ecco la contrapposizione fra questo santo di colore e la Santa, Rosalia, che discendeva addirittura (perché le è stato creato un albero genealogico, suo padre si chiamava Sinibaldo), discendeva addirittura da Carlomagno, era nobile, vergine, bianca, e quindi prevalse. Dico che bisognerebbe riscoprire questi santi di colore in Sicilia, per esempio la Madonna del Tindari, i San Calogeri. Bisognerebbe veramente, in questo nostro mondo che ormai si sta trasformando, con l’arrivo di questi poveri immigrati disperati, bisognerebbe riscoprire la storia di questi santi di colore in Sicilia.»

Ancora uno stacco nella registarzione. E ancora il via! di Giuseppe:

«In quest’isola dove l’uomo è solo, come ci ha insegnato Pirandello, è chiuso nella sua individualità, nella poca attesa che ha dalla parte sociale, dalla parte esterna, nella chiusura nell’ambito famigliare…, le feste religiose, come ci ha insegnato Sciascia, erano un momento di grande socialità, di aggregazione sociale, il momento in cui il siciliano usciva dalla sua solitudine e dove avveniva la comunicazione, avvenivano gli incontri, ed erano momenti assolutamente unici, e importanti anche per cercare di liberare le chiusure dell’uomo siciliano. Cogli anni poi queste feste religiose, rivedendole qualche volta come mi capita, si sono assolutamente snaturate, sono diventate molto esteriori, sono in mano alle varie pro loco… Voglio dire che i partecipanti alla festa ripetono per gli altri, sopratutto per quelli che li riprendono: finisce il momento religioso, e finisce anche il momento della comunicazione sociale, della partecipazione collettiva, e quelli che partecipano alla festa non sono più spettatori e partecipi ma, come dire, attori, attori di uno spettacolo che poi rivedrannoi a casa loro alla televisione. La televisione, naturalmente senza demonizzarla, ma forse bisognerebbe farlo, ha trasformato la nostra vita, e quindi ormai l’individuo vive nella solitudine della sua casa, vive nei momenti di pausa, così, guardando quello che Quasimodo chiama il video della vita: io lo chiamo il video della morte. Q!uesto nostro ormai è un paese che io chiamo telestupefatto, e i risultati poi si vedono in ogni campo, insomma, nel campo religioso ma anche politico e culturale, in ogni senso, in ogni aspetto della vita: chi non appare non è, non esiste, quindi bisogna cercare in tutti i modi di apparire, come sto facendo io in questo momento. C’è un’assoluta trasformazione che non sappiamo a cosa ci porterà: certo, a una omologazione del tutto in cui siamo immersi e che stiamo vivendo anche nel modo di esprimersi, nei modi di abbigliarsi, di vestirsi: basta guardare le nostre ragazze, i nostri ragazzi, col ventre al vento e i pantaloni sul ginocchio, il borsetto a tracolla e la testa rapata, così come hanno visto il commissario Montalbano alla televisione. C’è questo uniformarsi ai messaggi televisivi. E quindi anche le feste religiose, ahimè!, che avevano una loro verità e una loro profondità storica, ne hanno sofferto in questa trasformazione culturale».

A questo punto interviene l’osservatore delle tradizioni popolari Di Maio, il documentarista delle feste padronali, e la testimonianza diventa anche conversazione, sotto l’unico sguardo attento che registra la cinepresa, quello dello scrittore Consolo:

«Però —dice Peppe—, a questo proposito ti volevo chiedere una cosa. Tra le tradizioni popolari nell’ambito siciliano, forse la festa popolare di tipo religioso è quella che invece resiste di più. I canti popolari già è difficile riscontrarli, e anche i lamenti stessi .di cui abbiamo già trattato [fuoricampo, c’è da suppore, aggiungo io che, ripeto, non ero presente a questa registrazione]. Quelli con difficoltà resistono. Invece, ancora oggi, quasi a ogni paese, la festa popolare religiosa si mantiene. Come mai? Avresti una risposta?»

«Ci devo pensare, Giuseppe —risponde Vincenzo—. Tu, come la interpreti questa qui, questa conservazione? Ci sono ormai delle piccole isole, qua e là…»

«No —incalza Peppe—, io quello che dico è che però ogni paese riesce ancora a conservare la propria festa del Santo».

«Sì» —annuisce Vincenzo.

«Quindi —prosegue Peppe—, da un punto di vista sociale, in qualche modo, ancora il ruolo della Chiesa… io da questo punto di vista la volevo impostare… riesce ancora ad intecchire…»

«Sì» —ripete Vincenzo.

E continua Peppe: «Allora, è un problema ancora di fede, nonostante tutto…»

E Vincenzo: «Io dubito, sinceramente. Forse non lo è mai stato un fatto di fede; era un fatto, appunto, di tradizione popolare, di tradizione culturale, perché insomma… [e qui Vincenzo tira in ballo l’articolo dialettale] u siciliano non crede in Dio, crede nei Santi» —e sorride sornione.

«Non so», si sente la voce di Peppe.

Di nuovo uno stacco. Siamo alla conclusione delle riprese. Parla Vincenzo:

«Ricordo, col fenomeno dell’emigrazione meridionale nel nord dell’Italia, collaboravo allora con Il tempo illustrato, un girnale molto bello dove scriveva Pasolini, Giorgio Bocca, Davide Maria Turoldo… Sono andato a fare un’inchiesta in un quartiere periferico di Milano che si chiama Pioltello Limito dove c’era una comunità di Pietraperzia, perché c’erano le trafile del ricamo e si era formata questa comunità di pietraperziesi. E lì questi siciliani avevano trasferito anche la loro festa popolare, che era quella del Venerdì Santo con il Cristo morto e con i lamenti. Si eran fatti rifare la statua come quella del paese che avevano lasciato, identica, e quindi facevano questa processione il Venerdì Santo. Il parroco a un certo punto gli impedì di fare i lamenti, dicendo: —Ma cosa è questo, questi lamenti arabi? — chiamandoli con disprezzo arabi; veramente non sopportando l’intrusione, diciamo, di una cultura, di una tradizione siciliana antichissima in questo contesto industriale di Milano, della Lombardia».

Fine della registrazione. Ma, tra parentesi, mi viene da postillare: come non la sopportava nemmeno, questa intrusione, Elio Vittorini.

Dopo ci siamo avviati, Vincenzo alla guida, verso le campagne sopra Capo d’Orlando: ma ci fu l’incontro con quella sagoma di parente.

La propensione alla poesia, alla costruzione di una dizione nel contempo elittica e ritmica, è stata sempre del narrare sussultorio consoliano. Leggiamo dallo Spasimo: “Aborriva il romanzo, questo genere scaduto, corrotto, impraticabile. Se mai ne aveva scritti, erano i suoi in una diversa lingua, dissonante, in una furia verbale ch’era finita in urlo, s’era dissolta nel silenzio. Si doleva di non avere il dono della poesia, la sua libertà, la sua purezza, la sua distanza dall’implacabile logica del mondo. Invidiava i poeti, e magiormente il veneto rinchiuso nella solitudine d’una pieve saccheggiata – tutt’ossa del Montello questo mondo – «Le tue egloghe, amico, il tuo paesaggio avvelenato, il metallo del cielo che vi grava, la puella pallidula vagante, la tua lingua prima balbettante e la seconda ancor più ardua, scoscesa…» questo cominciava a dirgli, pensandolo da quella sua sponda d’un antico Mediterraneo devastato” (X).

Sciascia don Gaetano Sereni

PPP il silenzio dei poeti

Ma nel tentativo di dire si riparte dai libri (Spasimo)

E dai poeti (Valente)

E poi la storia del romanzo mancato, Amor Sacro

…

Sono andato a trovarlo a Milano nel dicembre del 2011. Era tornato lo Zigaga dell’infanzia. Un uccelletto avvolto in un bianco lenzuolo, che sarebbe stato fra poco sudario. Era sereno. Credo che non ci siamo abbracciati, il ricordo è confuso: ci siamo toccate le dita, sfiorandocele, forse anche le braccia: ci siamo salutati, senza dirci quasi niente. Una giovane donna, accucciata ai piedi del divano dove Vincenzo era disteso, è rimasta ad accarezzargli le mani mentre io passavo in un altra stanza. Chissà se per Vincenzo è stata l’ultima incarnazione di quella presenza silvana della Miraglia, quasi apparizione, nel Linguaggio del bosco. Conversavano. Ma dovrà essere lei, risalendo ad uno ad uno i pioli della sua scala d’ossa, a raccontare di quella conversazione.